|

[Front Page] [Features] [Departments] [Society Home] [Subscribe]

Propagating Boronia

Mervyn Turner

Editor's Note:

The late Dr Mervyn Turner was a long time member of the Victorian Region of the Society for Growing Australian Plants and was particularly active in the Foothills Group of that Region, where he was variously leader, newsletter editor, and show organiser. He had a particular interest in Boronia and other Rutaceae and was the foundation leader of the Rutaceae Study Group. His interest in the development of kangaroo paws (Anigozanthos sp.) for horticulture resulted in the well known "Bush Gems" range of cultivars.

This article is based on a lecture presented by Merv to the 1977 Biennial Conference of ASGAP in Perth. Although it lacks coverage of some more recent techniques (such as the use of smoke to promote germination) it remains an excellent and highly detailed, reference on propagation techniques for the Rutaceae.

What is presented in this paper is based on my experience, on reading, and on correspondence and discussions with a number of fellow enthusiasts. It is generally believed that Boronia is a difficult genus both in propagation and cultivation and to some degree this reputation is deserved. A mystique may well have developed which has hindered the more active exploration of cultivation and propagation. I have increasingly adopted the view that these problems will succumb to investigation and that general principles of propagation and cultivation apply to the genus. In this respect I have found Hartmann and Kester, Plant Propagation: Principles and Practices an invaluable general reference work.

I have propagated and grown or attempted to propagate and grow one or more taxa of more than fifty species of Boronia. There is both success and failure. A high proportion of the experience and a higher proportion of the success has been with propagation from stem cuttings. There is less experience and considerable failure with germination of seed. Beyond this there is a little experience with at least a few successful instances of propagation from air layers, grafts, cuttings grafts, root cuttings and off-set adventitious stems on roots (suckers). To this might be added transplantation of wild seedlings and the re-establishment of bare-rooted plants both wild and cultivated.

In all of this readers are reminded of the existence of legislation protecting the native flora and of the procedures and conditions which may apply to the collection of wild material.

|

|

| Boronia megastigma "Harlequin" |

Further collection, distribution and experimentation with wild material will be necessary if the horticultural potential of the genus is to be advanced. For a number of quite valid reasons this process must be carried out by enthusiasts. For example, the active manner of seed dispersal, typical of the genus, makes the collection of seed unattractive as a commercial operation with the possible exception of Boronia megastigma. As a further example, the limitation of many species to quite localised occurrences in specialised habitats widely separated geographically and with species represented in every state of Australia makes the more comprehensive collection of vegetative material a daunting task for any individual enthusiast or even a small group.

For this paper I take propagation to be a process which ends with the production of a relatively vigorous but immature plant. After this its cultivation commences, that is attention must be given to such matters as the suitability of a permanent environment and to the hopefully small degree of subsequent attention necessary for the immature plant to grow to maturity.

The remainder of this paper deals essentially with methods of propagation, Other aspects such as the natural history, elementary botany, and cultivation of Boronia are only dealt with incidentally, if at all.

Propagation by Germination of Seed

This method is not generally recommended. There are several as yet unresolved problems associated with this method and only the most enthusiastic should concern themselves with it for the time being.

This first problem is the availability of seed. Unfortunately, the fruits of Boronia are not persistent. Prior to ripening, intact seed is very difficult to extract, and even then may not be viable. Final maturation of the fruits, a four-carpellate capsule, is rapid and the seed is actively expelled from the capsule over a considerable distance. For a majority of species - those with a distinct seasonal flowering and fruiting period - the actual period of final maturation and dispersal is short. There is, therefore, a limited period each year for such species when intact fruit of near full ripeness may be collected. Such fruits will continue to actively expel seed and seed can be collected by placing the intact fruits in a large and almost fully enclosed container. The seed which according to species is pale brown to black, dull to shiny, and usually smooth is easily identifiable and separable from the chaff.

For a minority of species the flowering and fruiting season is much more extended (for example Boronia filifolia) and for such species initial flower buds, mature buds, flowers, and fruits can often be observed on a plant at the one time. Near ripe fruits can be easily distinguished and collected although proportionally in very small quantities.

There are a very few species where the petals return to enclose the developing fruit rather than being deciduous. In such cases, for example Boronia polygalifolia, entire petal-enclosed fruits may eventually fall beneath the plant and may be collected to yield seed.

If there are difficulties of timing in the collection of seed from wild plants, why not collect seed from cultivated plants? The first difficulty with this is that cultivated plants may produce little or no seed. There are good reasons why this should often be the case.

First, many species are known or suspected to be self-incompatible, that is pollen from the same flower, different flowers on the same plant, or different flowers on another plant of the same clone are incapable of effecting fertilisation. Two distinct plants, say of different clones, may be necessary for fruiting to occur. However, this may not be sufficient. The specialised co-evolved insect pollinators may be absent from the environment of the cultivated plants and other modes of pollination absent or ineffective. The Caucasian Honey Bee certainly forages Boronia but its method of nectar extraction appears unlikely to produce pollen transfer. As the number of taxa grew in my collection so did the proportion of taxa setting fruits, but there are still many taxa which do not set seed. This tends to confirm the matter of self-incompatibility in many species as well as the absence of at least many insect pollinators from the environment of these cultivated plants. In such conditions, there is a further possible complication - namely that hybridisation between species may occur which might defeat a purpose of such seed collection - namely the collection of species seed.

The second major problem concerns the viability of seed, the loss of viability over time, and of the factors of the seed's environment which may determine such viability and its loss. Unfortunately, very little is known of the seed ecology of Boronia. Circumstantial evidence suggests that there is a relatively rapid loss of viability under apparently normal storage conditions for many species. A better understanding of the seed ecology of Boronia may suggest methods of seed extraction, treatment, and storage which would increase or better maintain seed viability.

|

| "It seems clear for Boronia that there are dormancy "factors-mechanical" or biochemical barriers to or inhibitions of germination. " |

|

The third problem concerns germination itself. It seems clear for Boronia that there are dormancy "factors-mechanical" or biochemical barriers to or inhibitions of germination. These are difficult to investigate when the question of viability is unresolved. Again little systematic knowledge is available. Long term soaking, repeated leaching, and appropriate mechanical or chemical disruption of the normally hard seed coat have been claimed to result in germination in selected instances. Observations have been noted of abnormally high numbers of wild seedlings following abnormally high rainfall periods.

Recently, Mr J. Armstrong, of the National Herbarium, Sydney, indicated, in a personal communication, that leaching of seed beds with alkaline solutions of pH9 appears to trigger germination. This will be worth more systematic investigation. I have no direct experience of this method as yet.

For the time-being, then, this method is not generally recommended as one which will give reliable results. There are a few species where germination of seed does give reliable results. The most important case is that of Boronia megastigma. Wild seed is certainly collected regularly and in considerable quantity. Hence, seed available from commercial or institutional sources is very likely fresh. Spring or Autumn sowings on the surface of moist, fine-textured and friable media is recommended. For many years one or more Melbourne wholesale nurserymen have used open seed bed, broadcast sowing to produce quantities of semi-bare rooted seedlings for subsequent potting up.

In the meantime there is ample challenge to enthusiasts to collect seed and investigate the questions of viability and germination.

Propagation from Stem Cuttings

This method is generally recommended.

I have found with very few exceptions this method can be adapted to the successful propagation of many Boronia taxa. The method will be examined under a number of headings.

1. Source: Wild or Cultivated Plants?

Should stem cuttings be taken from wild or cultivated plants? Obviously, there is no single correct answer. Among other things there is the matter of access or availability.

Consider first the situation where cutting material can only be collected from wild plants. It should be remembered that polymorphism or variability is quite often a feature of a species. This is certainly the case with a majority of species of Boronia. Directly observable variation in certain characteristics may occur both within a locality and between localities, and where such variation is not an expression of environmental differences, such characteristics may be a basis of selection of cuttings material. Environmental differences can also contribute to observable differences, especially between localities. Natural pruning through frost or wind action can produce a compact dwarfed plant in one locality while the same plant in a more benign environment may be larger and more open in habit. Two recommendations result from this:

- Survey plants in a locality before selecting cutting material rather than simply taking cuttings from the first plant seen or the one easiest of access.

- Maintain records of localities so that comparisons of the plant's performance can be made between the wild and the cultivated environment.

One not infrequent variable characteristic is in the intrinsic capacity of the plant to initiate roots. This, of course, cannot be directly observed in the wild but it may pay to collect cutting material from a number of plants in a general locality rather than from a single plant even when another characteristic has been chosen for selection.

A juvenility factor may also operate in the capacity for root initiation. Hence, it may pay dividends to collect cutting material from seedling or immature plants, other things being equal.

|

| "Cutting material can be a source of infection or infestation for your propagation set-up or garden. Inspection and selection of cutting material in the wild is highly desirable to minimise such a risk." |

|

Cutting material can be a source of infection or infestation for your propagation set-up or garden. Inspection and selection of cutting material in the wild is highly desirable to minimise such a risk. It is a good habit to avoid cutting material with rain-splashed soil.

Also be sparing in the quantity of cutting material collected. Don't let your enthusiasm in the wild outrun your capacity to deal with the collected material later. Set yourself a target number of cuttings and collect material on this basis. It is possible to set cutting material in the field which minimises waste although possibly introducing other disadvantages. Occasionally, this may have beneficial effects on the initiation of roots. Boronia edwardsii is one species where I have obtained significantly better root initiation with field set cuttings.

If at all practicable, collect cutting material late in the flowers' season. This will permit ease of location and identification and, perhaps, permit selection for flower characteristics, for example flower colour. More importantly, while not necessarily the optimum season for root initiation, good results can usually be obtained at that time.

Finally, be prepared for the very rare variation. That is, don't go looking for one or even expecting one but as far as possible familiarise yourself with the general characteristics of the species of interest so that any marked variation will be more easily noted. Many horticulturally desirable taxa have been, and presumably will continue to be, located in this way. As a specific example, I am currently propagating a pink fully-double flowered form of Boronia pilosa discovered as a solitary roadside plant in south west Victoria by Mr Peter Ellis of Bendigo. I have observed bud sports on a few occasions in both wild and cultivated plants. Similarly natural hybrids are known in the genus Boronia and some have been propagated as horticulturally desirable taxa.

Cultivated plants can be a highly desirable source of cutting material. They are, obviously, easier of access and the timing of the taking of cuttings is much more at choice. Perhaps more importantly cultivated taxa already represent some selection for horticulturally desirable characteristics including that for ease of root initiation. Thus, if the cultivated plant has been propagated from a stem cutting it has already shown a capacity for root initiation.

However, another important possibility exists with cultivated plants. Such plants can be given one or more of a number of pre-treatments which yield beneficial results in either propagation itself or in certain features of the eventual plan - such as a good basal branch system.

It is known for a relatively wide variety of plant species that root initiation tends to be favoured by a nutritional regime high in phosphate and low, but not deficient, in nitrogen, by high levels of stored carbohydrate in the stem, by the presence rather than the absence of leaves on the stem cutting, and by the contemporary initiation of vegetative buds, and to be disfavoured by the contemporary initiation of flower buds. My experience, both direct and circumstantial, tends to corroborate these generalisations for Boronia. Pretreatments can be given to cultivated plants which induce or modify the time of onset of these conditions.

Other pre-treatments, such as pruning, can multiply the number of suitable cuttings available on on a single plant.

Application of nitrogenous fertilisers prior to the time of taking cuttings is not desirable since this tends to promote very active vegetative growth with the depletion of stored carbohydrate. I favour the application of a balanced (potassium, phosphorus, nitrogen) fertiliser in late summer or early autumn prior to flower bud initiation. With this pre-treatment, cuttings taken late in flowering or shortly thereafter, that is late Spring or early Summer according to species, tend to initiate roots in higher proportions than in the absence of this pre-treatment.

Tip pruning, especially of laterals, in the late flowering period tends to induce vegetative buds at the ends of these laterals. Such laterals with small vegetative buds moving into active growth tend to produce better and more frequent root initiation than comparable cuttings without such new vegetative growth. However, the new vegetative growth should not dominate the cutting.

Further tip pruning late in the active growing season will produce a more ramified branching system with a higher proportion of potential stem cuttings available in the following season.

Consideration should be given to growing stock plants in containers since this permits easier application of pre-treatments.

Given adequate attention to nutrition and to watering, container grown stock plants can be given higher levels of incident sunlight. This tends to the production of more compact plants and probably favours the accumulation of carbohydrate in stems.

2. Cuttings: What Type and Manner of Preparation?

With few exceptions, the ideal Boronia cutting is a relatively short cutting, 6 to 10 cm in length of a portion of a stem which has borne flowers that season but is now free of them or becoming free of them and where in the uppermost axils new vegetative growth has just been initiated. Very recent growth and material more than a year old should generally be avoided.

Within the above guidelines, three types of stem cuttings can be recognised. First there will be cuttings formed from short lateral and entire stems and where the cutting is formed by stripping the lateral stem down wards taking a heel. Any soft sliver on the heel should be trimmed away. Then there will be cuttings which terminate in a basal cut below a node and which divide into two types, namely those which terminate apically in another cut above a node or which terminate apically in an active growing tip. In all three cases new vegetative growth in the uppermost axils may or may not be present.

|

| "On the basis of experience I have developed a distinct preference for lateral cuttings taken with a heel and where new vegetative growth has just been initiated..... " |

|

On the basis of experience I have developed a distinct preference for lateral cuttings taken with a heel and where new vegetative growth has just been initiated in the uppermost axils, provided that the lateral while of appropriate length is not thin and weak.

With all types the other usual conditions of preparation apply. Leaves should be removed without bark damage from the lower half of the cutting. Where the residual upper leaves are large, for example in a relatively large leaved pinnate species such as Boronia alata, the total leaf mass can be reduced by trimming each leaf.

For most species no further preparation is necessary. For some species with a relatively thick bark a controlled wounding in the lower part of the cutting in the area of the heel or basal node can be beneficial. The area may be pricked, perhaps ten times, with a sharp needle. Alternatively, a sharp blade can be used to make a few light cuts parallel to the direction of the stem. This same procedure can be applied when re-setting cuttings which have developed large calluses and should be accompanied by at least partial removal of the callus.

3. The Use of Synthetic Auxins (Hormones): Yes or No?

Natural auxins produced in actively growing leaves are known to be associated with other agents in the regulation and control of growth processes in plants. Natural, and later synthetic, auxins were found to be nonspecific, that is the one auxin is effective in a wide range of plant species. Artificial applications of auxins were found to be beneficial in root initiation in many species and it was also found that the auxin could be applied directly to the base of the cutting.

Three basic methods can be used:

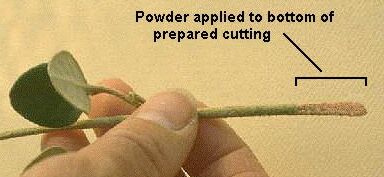

- First, application of the auxin in solid form. In this case the auxin is diluted by a suitable neutral solid, usually powdered talc.

- Second, it may be applied by soaking the base of the stem cutting in a very dilute solution of the auxin (of the order of 20 to 200 parts by weight of auxin to million of solution) for as long as 24 hours.

- Third, it may be applied by dipping the base of the stem cutting in a more concentrated solution (for a period no longer than a few seconds). For all three methods the. actual degree of dilution is varied according to the maturity or extent of lignification of the stem tissue, the higher concentrations applying to the most extensively lignified tissue.

| |

I have tried all three methods and also made comparisons between treated and untreated stem cuttings. I have had only a few sets of cuttings where untreated cuttings produced a higher proportion of rooted cuttings than a treated set. No difference or a difference favouring treatment was the result in almost all cases. Hence, I believe treatment is to be recommended on the argument that it rarely if ever produces a negative result and is often positive in action.

As to the three methods of application of auxin the evidence is less clear but tends to favour the powder method. This method is normally the most convenient to use and is to be recommended. Where a proprietary preparation is used one labelled for use with "semi-mature" wood will be the most effective. Both solutions and powders decline in potency with time due to chemical or biochemical degradation with powders being slowest to lose potency. In any event, a powder older than six or eight months since purchase is suspect.

4. What sort of Rooting Medium?

The rooting medium serves three key functions. First, it serves as a physical anchor for the stem cutting and later for the developing and extending roots. Hence, a rooting medium which expands and contracts according to temperature or variation in water content is to be avoided. Similarly an uneven mixture is to be avoided. A medium which retains shape or quickly develops this property is highly desirable since by inversion and careful removal of the container a set of cuttings can be inspected for rooting.

Second, it serves to provide air at the base of the cuttings. Oxygen of the air is essential at this point if roots are to be initiated. This favour of aeration is, in my opinion, one of the most significant factors in root initiation of Boronia. I have experimented with a large variety of media involving the following ingredients - various soils, sands and gravels, expanded polystyrene spheres, scoria, vermiculite, various composts, peat moss and various sifted and/or shredded materials such as dry leaves, bark, nut and fruit husks.

|

| "The rooting medium serves three key functions.....it serves as a physical anchor....it serves to provide air at the base of the cuttings....the medium serves to provide water for the cutting." |

|

For almost all Boronia species I now favour a medium consisting of approximately 80% by volume of relatively coarse angular-grained sand or gravel of relatively uniform grain size and substantially free of any fine-grained material either organic or inorganic. This is mixed intimately with the complimentary percentage of pre-sieved, soaked, and squeezed peat moss. German peat moss of uniform light colour and initial high density is preferable. Sands or gravels arising from decomposed granitic rocks are more suitable than alluvial sands or gravels. If fine-grained material is present initially in the sand or gravel it should be removed by repeated washing and decantation.

This medium should not be compacted forcibly in the container. I have found that sufficient consolidation occurs if the containers are filled with the loose medium, the top levelled, and the base of the container tapped a few times on a firm surface. A container giving a depth of medium of between 6 and 8 cm is adequate. Cuttings are inserted in this medium by making a narrow cylindrical hole of a diameter little more than that of the cutting. A graded set of skewers or knitting needles are admirable for this purpose. The cuttings are inserted for approximately half their length. The medium should not be pressed down around the cutting. The only further consolidation necessary is provided by the initial watering following insertion of the cuttings.

A further benefit of a medium as described above arises when a set of rooted cuttings in a single container have to be separated for potting on. The above medium crumbles and separates cleanly with virtually no damage to roots. Very fine particles of peat moss adhere to the roots protecting root hairs.

Third, the medium serves to provide water for the cutting. The general question of water relations will be discussed in the next section. At this point two things can be said in relation to water and the rooting medium. A poorly draining medium is to be strenuously avoided with Boronia - hence the type of medium recommended above. Anything approaching a perched water table will usually result in decay from the base up in Boronia cuttings. Secondly, I have found that cuttings can remain vital and roots initiate when the medium appears relatively dry - far drier than my experience previously would have suggested.

5. The Propagation Set-Up: What Environmental Conditions are Required?

The temperature of the medium and the temperature and humidity of the air surrounding the cuttings is of significance. Day time air temperatures of the order of 18o to 27o C are quite satisfactory provided that the temperature of the medium is not significantly lower. I do not generally favour bottom heat for Boronia. For most Boronia relatively uniform temperatures throughout the propagation set-up appear of greatest value.

| |

Propagation Set-up |

| |

As an indication, the following simple set-up gave excellent results with a wide range of species of Boronia when cuttings were set as indicated in the text and over the late spring and summer period.

The set-up consisted of a wooden-sided cold frame approximately 40 cm (16 inches) deep with a removable top consisting of a frame to which was attached black polythene insect screen fabric with approximately 50% air and light admission. This frame was set on a paved area adjacent to a brick wall facing east. Normally multiple sets of cuttings were close packed inside the frame and were sprinkled night and morning. Otherwise the lid was not removed. Temperature measurements inside this set-up indicated highly uniform temperatures during the bulk of daylight hours and from day to day over the summer period. |

Light conditions can also be significant. With the methods so far recommended, I have found root initiation better under conditions of partial shade rather than with greater light intensity even where temperature and humidity levels were contained to acceptable levels.

Water relations are very important. Transpiration resulting in water loss continues in stem cuttings and since roots are absent the major source of water uptake is absent. Some water is absorbed through the lower half of the cuttings from the medium but this may be insufficient to compensate for transpiration loss. Balance can be achieved by maintaining a high humidity in the area of the cuttings. The principal requirement is an enclosed space within which is a large wet surface area (and provided that this enclosure does not assume too high a temperature). Automatic misting systems can contribute to this effect but are primarily used to lower the temperature of leaves under conditions of more direct exposure to sunlight in glasshouse conditions. I do not generally favour the propagation of Boronia under misting conditions.

Currently, I propagate Boronia from cuttings in a polythene greenhouse under conditions of partial shade and where the greenhouse is ventilated on hotter days but humidity maintained by wetting of the floor and inner surface of the walls of the greenhouse.

6. Do Stem Cuttings Require Attention After Setting?

The answer is yes but attention should be minimal if earlier recommendations are followed and general sanitary practices apply. I have not found it necessary to apply regular regimes of fungicidal or insecticidal treatment but when they have been necessary I have not noted any adverse responses by the cuttings for the normally recommended horticultural treatments. Boronia are susceptible to infestation by scale insects even as cuttings and standard treatment by white oil emulsion applications brings adequate control without harm to the cuttings.

Routine removal of dead cuttings is desirable.

Cuttings may continue to grow, even flower, prior to root initiation. If a single dominant stem arises the cutting should be tip-pruned to encourage an adequate framework of basal branches.

The most regular routine may be inspection for root initiation and development. The times necessary for root initiation and sufficient development for potting up are quite variable from species to species, according to the nature of the stem cutting and the time of year when cuttings are set as well as the physical factors of the environment of the propagation set-up. However, apart from a few species, cuttings of Boronia can remain viable for very long periods without root initiation. I have had, for example, stem cuttings of Boronia crassifolia initiate roots after two years as set cuttings.

Inspection is necessary and is facilitated by the use of media which do not disintegrate when inspection is carried out. Previous reference has been given to this. A further reason for inspection which applies to certain species is that strong callus development may occur. Callus development is a different process to root initiation, although both tend to occur under similar conditions. Roots are initiated within the stem tissue whereas callus tissue develops externally to the stem. However, if the callus is large - partly enveloping the base of the cutting, the callus may form a mechanical barrier to the emergence of roots. When on inspection heavy callus formation is noted with no or at most a few root initials, all or much of the callus should be removed.

7. Potting-up and Growing-On: When and How?

The initiation and development of roots is not the end of propagation from stem cuttings. Experience suggests that there may be more difficulties with this stage of potting-up and growing-on than with the earlier stage of root initiation.

Cuttings taken and set in late spring or early summer will often be ready for potting-up by late autumn or early winter. In this situation the period coincides with the season when vegetative growth is at its lowest level. It also coincides with a time when there will be a considerable gap between the environmental conditions of the propagation set-up and external conditions. If rooted cuttings are potted-up at this stage, they should be kept for at least a week or so under conditions as similar as possible to that of the propagation set-up before progressively moving them to a less controlled and protected environment.

Another treatment is quite possible and may in the long term produce better results. The set rooted cuttings can themselves be left in their containers and progressively hardened-off and eventually "wintered" in only slightly protected open conditions. Protection from wind is the major requirement. Little growth of either stems or roots will occur until spring when, with the first obvious initiation of new vegetative growth, the cuttings can then be potted-up. If further root development has occurred then a balanced root and stem pruning can be done at the potting-up stage.

Whichever course is adopted the progressive hardening-off is a most important requirement.

What kind of potting medium is required? The major requirements are a medium of neutral to slightly acid properties and with a relatively open but free-draining texture. Fine fractions which tend to accumulate towards the base of containers are to be avoided. However, reasonable water-retaining properties are also desirable and a small fraction of such a material (e.g. peat moss, scoria, or suitable composts) can be added with advantage to the medium. With Boronia, as with many other genera, badly draining media tend to the onset of chlorosis and raw organic material to nitrogen deficiency as shown by excessively pale new vegetative growth. Where the medium can be expected to be very low in nutrients, a little balanced fertiliser can be incorporated in the medium. Pelletised synthetic products as well as blood and bone normally give good results provided that they are free of urea and its decomposition products.

In potting-up, it is important to realise that most Boronia do not develop extensive root runs. It is preferable to hill-up the medium in the container and to dispose the roots of the cutting as evenly as possible around this hill.

Additional potting medium can then be added with gentle consolidation and a watering-in. This process will tend to the development of a more even root mass.

Finally, the scattering of a little quartz-rich gravel on the surface of the medium in the container appears to exercise a general sanitary effect.

8. Exceptions and the Rule

A high proportion of taxa can be propagated from stem cuttings within the above guidelines - indeed for at least some taxa with relatively cruder technique. Some taxa none-the-less remain difficult. In at least a significant number of cases it is difficult to make any general statement about the ease or difficulty of a particular species since different variants of the species show different responses. For example, of three taxa I am currently growing and all identified as Boronia thujona, two propagate quite readily while the third is particularly slow to initiate roots.

The summary information which follows below should, therefore, be taken as only a general guide:

- Group 1

One or more taxa of the species in the following list pose no major problems in root initiation and in subsequent potting-up and growing-on.

Boronia alata, B.anemonitolia (including variety variabilis), B.clavata, B. crenulata (including variety gracilis), B.deanei, B.denticulata, B.filifolia, B.fraseri, B.gracilipes, B.gunnii, B.heterophylla, B.megastigma, B.mollis, B.molloyae, B.muelleri, B.pilosa, B.polygalifolia, B.tetrandra, B.thujona, B.thymifolia and B.viminea.

Boronia alata, B.anemonitolia (including variety variabilis), B.clavata, B. crenulata (including variety gracilis), B.deanei, B.denticulata, B.filifolia, B.fraseri, B.gracilipes, B.gunnii, B.heterophylla, B.megastigma, B.mollis, B.molloyae, B.muelleri, B.pilosa, B.polygalifolia, B.tetrandra, B.thujona, B.thymifolia and B.viminea.

- Group 2

One or more taxa of species in the following list pose no major problems but are slow either in root initiation or in subsequent growth following potting up:

B.albiflora, B.capitata var. clavata, B.coerulescens var coerulescens, B.inconspicua, B.juncea, B.microphylla, B.nana (all three varieties), B.nematophylla, B.parviflora, B.pinnata, B.rigens, B.safrolifera and B.serrulata.

- Group 3

One or more taxa of the species on the following list pose no major problems in root initiation, even if slow, but have a tendency for loss, sometimes severe, during the potting-up and growing-on stage.

One or more taxa of the species on the following list pose no major problems in root initiation, even if slow, but have a tendency for loss, sometimes severe, during the potting-up and growing-on stage.

B.algida, B.barkerana, B.citriodora, B.edwardsii, B.fastigiata, B.floribunda, B.Iatipinna, B.ovata, B.rhomboidea, B.rivularis, B.spathulata and B.subulifolia.

- Group 4

One or more taxa of the following species have shown consistent problems in root initiation being either very slow with continual loss or with a very rapid deterioration of the cuttings.

One or more taxa of the following species have shown consistent problems in root initiation being either very slow with continual loss or with a very rapid deterioration of the cuttings.

B.falcifolia, B.inornata, B.Iedifolia and B.purdieana.

I have successfully propagated the following from stem cuttings but experience is yet too limited to warrant any generalisations: B.anethifolia, B.bipinnata, B.crassifolia, B.Ianuginosa, B.repandra, B.rosmarinifolia and B.whitei.

A few special cases are worth noting.

There are several species whose natural occurrence is in conditions of relatively low rainfall and higher average temperatures. These species appear to be relatively intolerant of organic materials in the potting media. Low levels of organic materials are to be expected through oxidation in the above conditions. Better response is normally obtained in low organic, low nutrient, very free draining media. B.coerulescens, B.capitata, and B.ovata are examples.

There are a number of species with small pinnate leaves. More consistent results in propagation appear to arise when stem cuttings somewhat smaller then previously recommended are used. B.albiflora, B.pilosa, B.tetranda, and B.microphylla are examples.

Of the species of Boronia with compound terminal inflorescences there are several with small (simple) leaves and with long internodes. Boronia juncea is a prime example. Leaves tend to cluster in the areas adjacent to and immediately below the terminal inflorescences. For stem cuttings new vegetative growth tends strongly to arise from these areas. It is desirable in preparing cuttings to set the cutting with such an area immediately above the surface of the rooting medium. In this situation the area below a node from which roots will initiate will be at some depth below the surface of the medium. That is, the stem cutting will be inserted for considerably more than the more usual half its length.

Other Techniques of Propagation

A number of other techniques of vegetative propagation are worth considering by the enthusiast interested in enlarging the horticultural potential of the genus.

A major problem with cultivating Boronia in certain places in Australia concerns the susceptibility of the genus to attack by Phytophthora sp. especially under conditions of summer rainfall. Grafted plants using as a stock a resistant species is worth further exploration. This technique has been applied to other genera, for example Prostanthera. Grafting of a scion to an established stock or the use of cutting-grafts are both possible. For Boronia, there is a problem of scale in the size of materials to be handled. My own limited experience to date suggests that cutting-grafts might take precedence in exploratory work. Other genera of the Rutaceae could also be considered for use as the stock. for example, Correa sp.

Air layering might be considered especially for species which perform poorly in root initiation of stem cuttings. More than twenty years ago I had successfully air layered several exotic species-for example the Pineapple Guava (Feijoa sellowiana)-and also observed that wounded but only partly severed stems of a plant of Boronia heterophylla frequently calloused and the stem remained vital. Several air layers produced successful results with that species. More recently several other species have been tried with encouraging results.

Several species of Boronia produce off-set adventitious stems arising from roots. Forms of Boronia crenulata constitute a well known example. With this species such off-sets can be separated quite readily and, after root and top pruning to remove any damaged material, potted up with success. Some early trials with this species and with Boronia denticulata and Boronia thymifolia using 3-5 cm length of root set on a tray of rooting medium and covered by 1-2 cm of the same medium and kept constantly damp have produced a small proportion of adventitious stems with successful transfer to a regular medium. Again further exploration appears worthwhile.

Wild seedlings can be transplanted. i do not generally favour this method since at least as good results can be obtained from cutting material of seedling and immature plants. If it does become necessary or desirable to transplant wild seedlings, it is recommended that very small seedlings be used, perhaps only those with at most a few pairs of true leaves. It is also important to avoid root disturbance. Seedlings often arise in the wild in areas of soil wash for example, adjacent to road embankments. These are generally easier to remove without root damage. A simple technique is to press a food can open at both ends down over the plant and well into the soil. The soil adjacent to the exterior of the can can then be excavated and, if necessary the can can then be pressed further into the soil with further excavation. A blade can then be used to cut through the soil at the base of the can. The can and contents can be taken home intact where the lid of the can placed below the soil can be used to push out the plant and its soil intact ready for potting-up.

In very exceptional circumstances the attempt to re-establish bare rooted plants (wild or cultivated) can be justified. If transport is involved, the bare-rooted plant should be kept damp and cool in transit and treated at the earliest possible opportunity. Relatively severe root and stem pruning is necessary. Auxins may be applied to the residual roots. A low nutrient potting mix is desirable. The potted plant should be kept under conditions similar to those employed in the rooting of stem cuttings. My most exciting success in this regard was the Boronia lanuginosa sent from Groote Eylandt in the Gulf of Carpentaria which was treated in October, produced new growth in two weeks and began flowering in the following May - all in greenhouse conditions.

Concluding Remarks

Boronia as a genus contains many desirable horticultural taxa of which relatively few have been introduced to regular cultivation. Their horticultural desirability is mainly derived from their existence as dwarf to larger shrubs well-suited to the scale of domestic gardens, their great variability of habit, foliage, and the like, their delicate flowers usually carried in great profusion and in a considerable range of colours, the presence of interesting leaf scents in many species. and of attractive flower scents in some species.

I am now convinced that the number of desirable taxa in regular cultivation can be increased by due attention to and further investigation of methods of propagation especially by asexual methods. This, together with a better knowledge of their subsequent cultivation, should make them increasingly successful and popular with the Australian native gardener.

This article is a reproduction of a paper presented at the ASGAP Federal Seminar, Perth, 1977. The paper has been edited slightly to eliminate out-of-date references.

Photos by Brian Walters except Boronia falcifolia by Barbara Henderson.

[Front Page] [Features] [Departments] [Society Home] [Subscribe]

Australian Plants online - September 2001

Association of Societies for Growing Australian Plants

|