|

[Front Page] [Features] [Departments] [Society Home] [Subscribe]

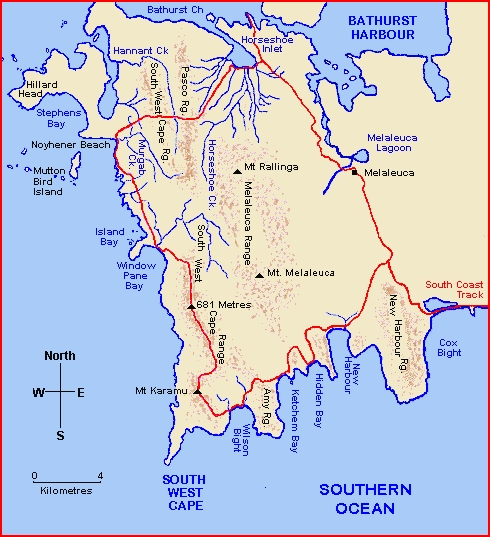

South West Cape Range - Tasmania

Harry Loots

An essential ingredient to the appreciation of the immaculate landscape of Tasmania's South West Cape is exposure to its fickle weather. We achieved this in January 2000 when we experienced the foul and fair conditions produced by the Southern Ocean. South West Cape, a sharp granite protrusion into the vast ocean surrounding the Antarctic, is directly exposed to winds, which otherwise circle the globe unimpeded. Sailors, using these winds to circumnavigate the world, called them the Roaring Forties. We approached the South West Cape Range as a westerly stream of moist air, blown in from the cold sea and elevated by the range, dumped abundant rain. This Range was uninviting.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wilson Bight (top and centre)

Near Window pane Bay (bottom)

Photos: Harry Loots |

Waiting for a lull we prudently camped at Wilson Bight where we optimistically watched the train of clouds, a daylong pageant of cloudscapes, many with a heavy shower, issue from the Cape's crest to our west. Instead of ascending into the storm we wandered the beach among equally turbulent dark, glistening rock formations. Twisted metamorphic stratum jutted out to sea to transmogrify, in our imagination, as whimsical mini mountain ranges washed by foamy waves and tidal surges that dragged strings of pearl and green ribbon seaweed around their foothills. Meanwhile, a capricious sky, a flux, changed from a blithe blue heaven, to joyous fluffy white clouds that raced with the speed of horsemen, to daunting dark grey masses that streamed showers.

The previous day while crossing from Ketchem Bay to Wilson Bight I was nearly knocked senseless by a malevolent salutation of hailstones. It was sent to greet us at attaining the Amy Range ridge. Stunned and in flight from a freezing wind we nearly walked off down the wrong spur. Navigational errors are often made during moments of insanity or periods of relaxation. I decided to lift my game, to consult the map more frequently, even in a gale where wind, rain and confusion prevail.

Please don't mistake this as a complaint about the appalling weather. Not tasting the sometimes bitter, but always exciting, relish of cruel wet weather would have left me hungry, my appetite for the South West wilderness experience unsatisfied.

Initially, foul weather delayed by a day our flight into Melaleuca. When the small plane touched down on the abandoned tin mine's dirt airstrip I breathed a sigh of relief. I was unwell during the rough flight. However, after a few kilometres we were steamed up and perversely enjoyed the rain and 12oC summer temperature.

It rained, drizzled, poured or looked like it was about to rain for three days while walking to Wilson Bight. Our first campsite at New Harbour was dark, soggy and leech infested. The melaleuca and banksia forest growing on the fore dune provided protection from the wind but was a dreary campsite. Lindy was lucky to enjoy fresh fish for two nights, left for us by generous fishermen. We had seen their fishing trawler, in between mists of rain, sheltering from the storm in the lee of New Harbour's high eastern cliffs. Further along the coast at Ketchem Bay and Wilson Bight we camped on the beach. At these more salubrious leech free locations, cliffs and dunes protected us from the westerlies. Our living room had an open prospect where we cooked, ate, slept and meditated; serenaded by crashing waves on a shoreline changing with time and tide.

After the sojourn at Wilson Bight our patience was rewarded with improved weather. The South West Cape Range could now be traversed and we climbed Mount Karamu under a static sunny sky. An initial vertical ascent through thick coastal scrub, a scramble up a ladder of exposed roots and trunks, led to open ridges of low growing heath and grasses. Heaven's white horses, the broadcasters of shadow and rain, had vanished and our concern turned to sunburn. We had read in the Hobart Mercury that the hole in the ozone layer above Tasmania had caused hideous skin blisters. Lindy went into purdah and protected herself from ultra violet radiation with a scarf over her hat and around her face.

Although at a relatively low altitude the landscape had Antarctic features. White rocks were roughly painted with the green hues of alpine pasture. Rounded ridges with a paucity of vegetation described a hostile environment. Exposed to the direct fury of the Southern Ocean's freezing winds, vegetation taller than 30cm is regularly pruned. Rocks protect aberrant vegetation. Monoliths protrude above the meadow like giant tombstones; their bare white stones a testament to the persistent corrosive power of the wind. On their lee sides, mats of vegetation hug the rocks, which are generous protectors.

The ridge walk was a surreal experience. Cloudless, an expansive blue sky complimented the ocean, which grew vast as we climbed higher on the range's promontory. Strange electronic sounds seemed to be coming from the top of the ridge. I imagined extraterrestrial aliens and UFOs but there was nothing quite that bizarre. The source of the cacophony was a green pool overpopulated with frogs barking at midday. Set in among barren rocks high on the ridge a tiny sedge community screamed in isolation.

|

|

Two spectacular plants of the south west:

Agastachys odorata (left) - a member of the Protea family and the only species in the genus Agastachys.

Dracophyllum milliganii (right) - a shrub in the Australian heaths family (Epacridaceae).

Select a thumbnail image or highlighted name for a higher resolution image (48k and 43k).

Photos: Harry Loots

|

We were blessed by two opportune natural events. Standing water found on top of the range quenched our thirst and the exceptional calm weather permitted a comfortable camp on the summit. The day's walk had been more protracted and exhausting than anticipated. When we reached the peak at 7:30 pm there was no alternative but to sit down and enjoy the view.

We savoured the world from our 681metre aerie. Down through the valleys of the coastal ranges we recognised New Harbour beach before the New Harbour Range. Far out in the Southern Ocean Maatsuyker Island's lighthouse cast its beam in the twilight. South West Cape stretched southward, its rocky spine ending as a sharp point, a finger pointing to the Pole. Tomorrow's campsite lay beneath us at Window Pane Bay. Its beach, a white arc of sand, formed a margin between the dense forest growing on the dunes, blown deep into and up the valley sides, and the ocean. In the evening there were the northern lights of cray fisherman's boats anchored near Mutton Bird Island. To our north east, beyond the rugged massive of Mount Rallinga, we glimpsed Horseshoe Bay and its swampy flats where we would regain the track to Melaleuca.

Two days later, after crossing the dune behind Window Pane Bay, we were again seduced by nature's glory. At Island Bay a multitude of islands, a restless landscape of twisted strata was subdued; fixed by a placid sea. Knife-edges, broken rocky folds produced by violent subterranean forces, pierced the sky. Folded stone excavated by the sea's relentless surge formed arches and deep dark sea caves from which issued aprons of white sand. I imagined that recluses could meditate here. This was a place where cave dwelling hermits could find peace contemplating a divine visage.

We kept our own company for eight days. Our sense of solitude was palpable but there was a risk. If, in my imagination, this mystic country could accommodate contemplative hermits it also provoked panic. This occurred further up the coast when we wandered absent-mindedly off the track. We became imprisoned in an impregnable thicket of serried Leptospermum. A dense woody palisade locked us in its maze for a frantic hour before we were liberated. There is always the fear of losing our way.

The ungraded track between Window Pane Bay and Noyhener Beach follows an old alignment, a straight line that drops abruptly into steep gullies, passes through wallaby holes in the dense vegetation and then ascends steeply to the ridge. It had been cut for shipwrecked sailors to escape the wilderness.

At Noyhener Beach we found a rich supply of flotsam and jetsam provided by the Southern Ocean's fishing industry. Detergent bottles labelled in Spanish had been blown in from South America. Large plastic containers, for fresh water, and plastic fish crates are washed off small boats. Japanese whisky and beer bottles lie buried by the sand. Beachcombers have fashioned this refuse into camp furniture. Campsites have been made comfortable. Orange net ropes strung between trees are used for hanging and drying clothes. Large brightly coloured balloon floats mark the tracks from the beach as well as decorate the camp with baubles. The campsite, set in amongst trees high on the dune, is protected from the wind by a barrier of thick bush. Here plastic fish boxes, planks and flat plywood form a table with surrounding bench seats. At night it was a seductive outdoor living room. A candle in a bottle cast a warm glow on the evening's activities.

Our day off, before the climb over the Ranges to Horseshoe Inlet, was spent loitering about the beach. Noyhener is a long flat strand planed smooth by wind and wave before a vast complex of high dunes. Bracing ourselves against a strong southerly gale we passed broken wooden hulls with twisted copper spikes protruding from the fine-grained quartz detritus. Unpleasant sea wrack where flies feasted on a dead dolphin and seal produced a revolting stench. Flies were also drawn by the odour of rotting seaweed with its population of jumping nits that tickled our legs.

Next morning we enjoyed our last view of beach and ocean from South West Cape Range. The wind had turned to the west bringing a heavy downpour and we peered through mist at a green and white mosaic formed by shrub and sand on the undulating dunes along the coast. Without the guidance of a track, today's challenge was to navigate accurately. The bald nature of the ranges gave us simple bearings for a direct approach. We negotiated a route across a series low growing heaths and where possible avoided the bush. A scramble up a long white rocky ridge led to the crest of the Cape Range. After a slide down to Hannant Creek we pushed through some dense shrub to ascend the Pasco Range. To our relief from now on it was all downhill.

I imagined that the end of our walk was in sight but I was deluded. I had reckoned on a lengthy walk along an anonymous ridge to Horseshoe Inlet followed by a half day's walk into Melaleuca. However, the weather closed in and we spent a ttent-bound evening and morning immured by a gale howling off the bay. The onset of cold wet weather also dampened our enthusiasm for swimming across the two deep creeks that obstructed our along-shore path. Fortunately by midday a clearing sky and an ebb tide permitted a crossing on the creeks' shallow bars. We passed their deep channels by contrarily walking 20 metres into the Inlet where it was only waist-deep.

We completed our South West Cape circuit in brilliant sunshine. The creek crossings were the final obstacles to our return to the security of Melaleuca and our reversion to being Homo domesticus. But we felt a sense of disappointment. While no longer exposed to an unrelenting tempest, we now lost our sense of seclusion and our consciousness of self-sufficiency. After our dreary diet of dehydrated food we were dreaming about a meal in a Hobart restaurant.

Originally published in the newsletter of the Harbourside Group of the Australian Plants Society (NSW).

[Front Page] [Features] [Departments] [Society Home] [Subscribe]

Australian Plants online - September 2001

Association of Societies for Growing Australian Plants

|