A Short History of the Cultivation of Grevillea in England

Tony Cavanagh

Grevilleas were among the early introductions from Australia to European Botanic Gardens and to private nurserymen. according to contemporary records I have been able to examine, while only three species were grown before 1800, a further seven became available over the period 1800 – 1820. The “boom” years were between 1820 and 1840 when, largely through the efforts of Alan Cunningham, Banksian collector in New South Wales, some 28 new species were introduced.

Additional plants were cultivated spasmodically over the intervening years to well into this century, and many species were reintroduced but the passion for collecting new and exotic species, so evident in the early part of the 19th century, had evaporated. Nevertheless a few grevilleas are still grown today at Kew, at the Royal Horticultural Society’s garden at Wisley and even outdoors in southern England and in France. For example, Don McGillivray (1975) mentions that bunches of the decorative foliage of G.longifolia can be purchased in London at Christmas, the source being cultivated plants from England and France.

Tracking down what Australian plants were grown in Europe is a fascinating and absorbing subject but it has its frustrations. Many of the species names have now been changed and the details given in the literature are all too often vague or occasionally contradictory. There are sure to have been other species introduced which were not recorded or ones which never flowered and hence could not be identified with certainty. It is also quite probable that some were misidentified eg. G.?vestita which one source gave as having purple flowers! Other species such as G.ilicifolia and G.acanthifolia were often confused. Then again, plants were introduced under pseudo-scientific or horticultural names and unless a type specimen survived (highly unlikely for garden plants) or it was illustrated and the illustration has sufficient diagnostic detail, it is nearly impossible to identify such plants. Finally, there were many other names used for Grevillea so it is highly likely that I have missed plants through not checking all possible sources. For example, the following generic names have all been listed for Grevillea – Anadenia, Embothrium, Fitchia, Lysanthe, Lyssanthe, Manglesia, Molloya, Plagiopoda, Ptychocarpa, Strangea and Stylurus!

|

|

|

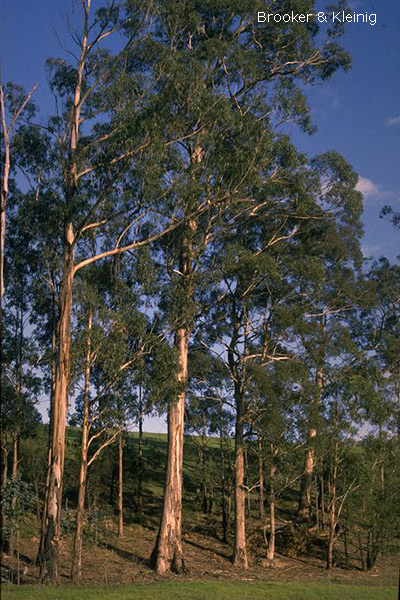

| An early introduction (1803) was Grevillea montana (left). Grevillea acanthifolia (right) was one of the species sent to Europe by Alan Cunninngham Photos: Neil Marriott and Brian Walters |

||

The history of cultivation is intimately tied up with the history of botanical exploration in Australia; hence it is necessary, before discussing the plants themselves, to consider briefly some aspects of the early collection of Australian plants and especially the role played by Sir Joseph Banks.

History

Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander on Lieutenant James Cook’s first voyage (1768-1771) collected large quantities of botanical specimens (most of which were not described until many years later) and some seed. The variety of seeds was apparently not great as I can trace only six Australian species which are attributable to Banks from this voyage.

“Somewhat surprisingly, there was not a

botanist, naturalist or recognised gardener with

the First Fleet ………”

In 1772, Banks was appointed director of the Royal Gardens at Kew and in 1773, Banks was elected President of the Royal Society, a position he held until his death in June 1820. Clearly, these positions gave him great influence and he set to work to stock the King’s garden with exotic flora from all over the world. His contact with Australia ensured that he maintained an active interest in a country whose settlement he had so strongly advocated, and Governor Phillip, from the founding of New South Wales in 1788, sent back both seeds and plants to Banks. Somewhat surprisingly, there was not a botanist, naturalist or recognised gardener with the First Fleet, a fact which is hard to understand in view of the considerable quantities of seeds and plants which were brought out to help establish the infant colony. However, people such as the Colonial Chaplain, Reverend Richard Johnson and Surgeon-General John White collected plants and animals which were sent to Banks and others in England.

In 1791, Banks appointed the superintendent of convicts, David Burton, at 20 pounds a year to collect seeds, living plants and specimens which were to be exclusively supplied to Banks. Unfortunately, Burton was accidentally killed on a duck hunting expedition in 1792 and it wasn’t until 1800 that the next official Banksian collector arrived, the rather prickly George Caley. He was to do much in the next 10 years to increase Europe’s knowledge of Australian plants through the supply of living material and seeds,

The greatest (and last) Banksian collector was the famous Alan Cunningham who, despite various brushes with officialdom did so much to increase our knowledge of the Australian flora through his expeditions and writings. Appointed in 1816, he died in 1839, being responsible in the intervening years for supplying to Europe seeds of a large number of species including at least 16 grevilleas. He also described many new plants, among the grevilleas G.rosmarinifolia and G.wilsoni being two of the best known.

While most material went to Banks and was distributed by him to various Botanical gardens such as Kew and Cambridge and to a select few of the King’s favourites, right from the outset there existed an extensive clandestine trade in botanical and zoological specimens and seed; Banks’ desire for a monopoly probably ensured that Naval and military officers, even convicts, apparently found a ready market for the curiosities of New Holland. An interesting figure of this period is the Scotsman William Patterson who, though a soldier and later a Colonel in the New South Wales Corps, had from an early age studied botany extensively. It is believed that his appointment to the New South Wales Corps was due to Banks’ influence and probably in return, Banks expected to receive seeds and specimens from New South Wales. Paterson arrived in Sydney on October 16 aboard the “Admiral Barrington” and embarked on the “Atlantic” for Norfolk Island with the Island’s Governor Phillip Gidley King on October 25. He apparently made the most of his 9 days in Sydney and collected seed and specimens which were forwarded to Banks and apparently to private nurserymen. Andrews Botanists Repository (an early botanical publication) has a tantalising comment in 1800 when describing Embothrium sericeum (now G.sericea)

“……About the end of the year 1791, the seeds of this plant with many others were received by Messrs. Lee and Kennedy of Hammersnith, transmitted to them from New South Wales by Colonel Paterson…..“

|

|

|

| Grevillea buxifolia (left). Grevillea sericea (right) Photos: Brian Walters |

||

Paterson collected extensively on Norfolk Island and later in New South Wales and Tasmania and was eventually to become Acting Governor of New South Wales on two occasions – a job he did much less successfully than his botanising. His importance to our story is that he introduced the first three grevilleas to be grown in England:

- G.buxifolia (1791) via Lee and Kennedy

- G.linearifolia (1791) via Sir Joseph Banks

- G.sericea (1791) via Lee and Kennedy

G.buxifolia was probably the first to be flowered – in 1795 at Lee and Kennedy’s nursery.

Later Collectors

Some 38 or 39 Grevillea species had been introduced by 1840 but in the second half of the century, interest in Australian and South African Proteaceae declined and new species made much more spasmodic appearances. The earliest Western Australian species were G.aspera, G.concinna and G.pulchella which were almost certainly collected by William Baxter on the south coast in 1823/1824. In the late 1830s, G.bipinnatifida (1837), G.crithmifolia (1840), G.flexuosa (1840), G.glabrata (1837) and G.thelemanniana (1838) made their appearance. The Austrian Baron Karl von Huegel, who visited Perth and King George Sound in 1833-1835, was probably responsible for these. The main evidence I have for this view is that they were among the plants growing in Prince de Demidoff’s garden near Florence, Italy in the 1850s (Prince de Demidoff purchased many of the plants from Baron von Huegel’s garden in Vienna when this was sold around 1848). James Drummond then enters the picture but, despite his love for the Proteaceae, he only appears to have supplied seeds of a few new species including G.eriostachya (1845) and possibly G.quercifolia (1845).

|

|

|

| Grevillea bipinnatifida (left). Grevillea flexuosa (right) Photos: Brian Walters |

||

In the eastern states, Von Mueller at Melbourne and Schomburgk at the Adelaide Botanic Gardens forwarded seeds and plants including G.annulifera (approx.1880), G.ericifolia (1868) and G.macrostylis (approx. 1868), while early Australian seed companies were also involved, eg., seed of G.oleoides was purchased by Kew in 1917 from J.Staer and Company, Wahroonga. Guilfoyle at Melbourne continued von Mueller’s work (he introduced G.hookeriana in about 1885) and several private individuals also played a part. At least one interesting hybrid resulted from the growing of Australian grevilleas in England – G.x semperflorens which originated as a cross between G.thelemanniana and G.juniperina var sulphurea. It forms a much branched shrub to 2m and, with its yellow-green flowers, looks most attractive. I wonder if it is grown in Australia?

Cultivation

Grevilleas were popular glasshouse (and outdoors) subjects because they were usually hardy and formed neat and compact pot plants, A number also flowered in winter when little other colour was available. They were described as growing easily in “. . . equal mixtures of loam, peat and sand . . .” while “. . . ripened cuttings root without difficulty under a hand glass . . .“, “. . . seeds often ripen in abundance on some species from which young plants may be obtained . . .”

While most grevilleas were glasshouse or conservatory plants (ie., they were grown under glass for at least the worst of the winter) some proved very hardy and could he grown out of doors. Thus a plant of the type form of G.rosmarinifolia, which had not been collected since 1822, was located In the Edinburgh Botanic Gardens growing outside against a building (McGillivray 1975). Other hardy species included G.longifolia (previously mentioned) and G.juniperina form sulphurea which is “. . . one of the hardiest members of the genus in cultivation in the British Isles, thriving in favoured positions out of doors in the south-west and as far east as Sussex and South Surrey . . .”

The “type” form of Grevillea rosmarinifolia

Photo: Brian Walters

The loss of interest in Australian plants, including grevilleas, after the 1840s had its origins in two main events: a change in peoples tastes and gardening fashions and a consequent change in glasshouse design and function. The days were passing when gentleman gardeners maintained glasshouses packed with exotic material from around the world. Instead fashions turned to fancy floral beds, the growing of smaller and easier-to-cultivate specimens and, most importantly, the growing of ferns and tropical softwood plants. The latter activity became all the rage and glasshouses were modified accordingly. Heavy watering was necessary and drainage of soils in the pots was not regarded as important – moreover, the ferns and softwooded plants required a high humidity “. . . that is the death of the proteas from the Cape and the banksias from Australia . . .”. Kew Gardens apparently used dry flue heating into the 1850s and proteaceous plants lasted longer there than in most other gardens. Indeed some were at least 50 years old as pot plants in 1856 while several banksias grew to the stature of small trees in the Kew conservatories. The Kew collection of Proteaceae reached its peak in the period up to 1860 when some 154 species of Australian and Cape plants were being grown. By 1889 it had declined to about 120, largely because of a reduction in the number of Cape plants. It would be interesting to know how many Proteaceae are grown at Kew today.

“The days were passing when gentleman

gardeners maintained glasshouses packed with

exotic material from around the world.”

A list of grevilleas grown in England, together with their dates of introduction, is given in Table 1, but I would be the first to admit that it is almost certainly not complete.

In summary, there were at least 53 species that can be identified with reasonable certainty as having been grown in England up to around 1920. Several were also grown in continental Europe and, particularly with a number of species introduced by Hugel, it is likely that they were transmitted to England from the Continent. In addition there were a further 10 introductions which we have been unable to identify; some are possibly just horticultural names and may well refer to species in the list of 53. There are also a further half dozen for which there is only patchy information but if their claims are accepted, the list could be as high as 57 or 58. This is certainly the largest number of any Australian proteaceous genera and it says something for the versatility and attractiveness of grevilleas as pot plants that there was so much interest in them, especially when it is remembered that nearly all were raised from seed.

Table 1 : Grevilleas cultivated in England, 1792 – 1920

| Present Name (note a) | Year First Introduced | Name Used (if different to Col.1) |

Collector |

|---|---|---|---|

| G.acanthifolia subsp.acanthfolia | 1822 | A.Cunningham | |

| G.agrifolia | 1821 | G.aquifolia | A.Cunningham |

| G.alpina | 1856 | G.alpestris | |

| G.annulifera | 1880 | F.von Mueller | |

| G.arenaria subsp.arenaria | 1803 | G.Caley | |

| G.arenaria subsp.canescens | 1822 | G.cineria | A.Cunningham |

| G.aspera | 1824 | ?W.Baxter | |

| G.asplenifolia | 1806 | G.Caley | |

| G.banksii | 1856 | G.fosteri | C.Moore |

| G.baueri subsp.baueri | 1822 | G.pubescens | C.Fraser |

| G.bipinnatifida | 1837 | ?ex Hugel | |

| G.buxifolia subsp.buxifolia | 1792 | Embothrium buxifolium | W.Paterson |

| G.buxifolia subsp.phylicoides | 1802 | Stylurus collina | |

| G.caleyi | 1829 | G.blechnifolia | A.Cunningham |

| G.concinna subsp.concinna | 1824 | W.Baxter | |

| G.crithmifolia | 1840 | ?ex Hugel | |

| G.curviloba subsp.curviloba | 1839 | G.lawrenceana | |

| G.drummondii | 1858 | ?J.Drummond | |

| G. x ericifolia | 1878 | F.von Mueller | |

| G.eriostachya | 1839 | ||

| G.fasiculata | 1872 | ||

| G.flexuosa | 1836 | Anadenia flexuosa | |

| G.floribunda | 1835 | G.ferruginea | R.Cunningham |

| G. x gaudichaudi | 1823 | ||

| G.gillivrayi | 1854 | ||

| G.glauca | 1821 | G.gibbosa | A.Cunningham |

| G.hilliana | 1862 | ||

| G.intricata | 1870 | Burges | |

| G.juniperina | 1822 | A.Cunningham | |

| G.juniperina form “sulphurea” | 1823 | ||

| G.lavandulaceae | 1850 | G.rosea | |

| G.linearifolia | 1792 | Embothrium lineare | W.Paterson |

| G.macrostylis | 1868 | F.von Mueller | |

| G.manglesii subsp.manglesii | 1836 | Manglesii glabrata and Adadenia manglesii |

|

| G.manglesii subsp.ornithopoda | 1850 | ||

| G.montana | 1803 | P.Good | |

| G.mucronulata | 1805 | G.acuminata | G.Caley |

| G.oleoides | 1917 | J.Staer & Co. | |

| G.parallela | ?1821 | G.ceratophylla | A.Cunningham |

| G.parviflora | 1824 | ||

| G.preissii | 1838 | ||

| G.pulchella subsp.pulchella | 1824 | W.Baxter | |

| G.quercifolia | 1838 | G.brachyantha | |

| G.refracta | ?1821 | G.heterophylla | A.Cunningham |

| G.robusta | 1829/30 | A.Cunningham | |

| G.rosmarinifolia | 1824 | A.Cunningham | |

| G.sericea | 1792 | Embothrium sericeum | |

| G.speciosa | 1809 | ||

| G.sphacelata | 1825 | ||

| G.synapheae subsp.synapheae | 1836 | Anadenia gracilis | |

| G.tenuiflora | 1836 | Manglesia tenuiflora | |

| G.tetragonoloba | 1886 | G.hookeriana | W.R.Guilfoyle |

| G.thelemanniana | 1837/38 | ?ex.Hugel | |

Notes:

|

|||

Comments on some of the Plants

Grevilleas figured-prominently in horticultural magazines of last century, notably in Curtis’ Botanical Magazine, Loddiges Botanical Cabinet and Andrews Botanists Repository. Most articles discussed propagation and cultivation of each species and usually featured a full colour reproduction of a flowering specimen. Some of these are beautifully executed, the illustration in Curtis’ of G.intricata (t. 1919) being particularly graphic. From these articles we can also learn much about the interest taken in our plants and the following extracts from the pen of Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, Director of Kew, reveal the esteem in which he held Australian grevilleas:

“Amongst the most graceful (of ornamental plants) is G.robusta which is perhaps the most widely used foliage plant for table decoration that ever was introduced into Europe” (Curtis Bot.Mag., t 6879, 1886)”

On G.ericifolia (now G.rosmarinifolia):

“. . . it is a very attractive ornament in both the conservatory and the temperate house , . . and is an example of the . . . vast number of beautiful and interesting greenhouse plants still to be introduced into cultivation from Australia whose once-prized relatives have been elbowed out of cultivation by soft-wooded greenhouse plants of greater show but less grace and interest …” (Curtis Bot.Mag., t 6361, 1878)”

In 1889, he was to write (Curtis Bot.Mag., t 7070):

“. . . it is much to be wished that the cultivation of the more beautiful and singular Proteaceae of the Cape and Australia which may be said to have been in abeyance for nearly a century, should be resumed . . .”

Regrettably, Hooker’s words were not heeded and, as far as I can ascertain, very few Australian Proteaceae are grown in Europe today.

Some plants were introduced under names which are or were recognised as “true” species. However, because no herbarium specimens have survived or because illustrations which exist do not show diagnostic characteristics, their true identity is unclear. They include the following:

- G.serica subsp.riparia, claimed to have been introduced before 1809 as Lysanthe riparia.

- Possible earlier introduction of G.arenaria than the 1803 usually quoted.

- Under the name “Lysanthe cana“, which Robert Brown believed to be G.arenaria, a plant flowered in 1804.

- G.longifolia (1830) but no further information is available.

- G.?vestita, possibly introduced by Hugel around the late 1830s. Olde and Marriott discuss the problems with identification of this species (p.113, Vol.1).

- In another reference I have used, the flower colour for the plant referred to as “G.vestita” is purple – almost certainly a misidentification.

- G.ilicifolia has been grown under this name in a number of European gardens. However, at least one other author has listed the plant as a synonym of G.acanthifolia.

Further Reading

Olde, P and Marriott, N (1994), The Grevillea Book, Vols.1,2,3, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst, New South Wales.

This article is a composite of two articles written by Tony Cavanagh for the newsletter of the SGAP’s Grevillea Study Group in August 1994 and March 1995.

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)