Australian Native Succulents

Attila Kapitany

The African and American continents are well-known for their remarkably abundant and interesting succulent plants. Europe, Asia, Madagascar and the Canary Islands are also well-recognised for their diverse succulent flora. By comparison, Australia is seen by many as being devoid or almost devoid of succulents, when in fact this is incorrect. Of the 20,000 or more Australian vascular plant species, at least 400 can be regarded as succulent. Even though this is proportionately a very small number in comparison with most of the aforementioned other places, they should not be totally discounted.

Succulent, Succulents or Succulence?

The word 'succulent' is widely used as a noun (for example, 'a succulent'), as well as an adjective (for example, 'a succulent plant'). Botanists use the more accurate term 'a succulent plant' to describe plants having succulence. 'Succulent plants', often from arid and seasonally dry regions, have adapted to survive dry periods by having water storage tissue (succulence) in their leaves, stems, trunks or roots.

What influences the degree of succulence? The thicker and more water-filled the plant's structure, the more succulent it is. As a result, plants can vary considerably in their degree of succulence, not only between the different species, but even within the same species growing under different conditions.

Some plants are always very succulent, like Carpobrotus; while others, like Doryanthes, appear to be barely succulent, if at all, so the line drawn between general plants and those which are considered succulent is very arbitrary. The cut-off point is the subject of much debate. Plants that are considered succulent are fleshier than other plants in one or more of their parts, such as the leaves, stems, trunks or roots.

Those plants which have evolved swollen water storage organs, above or below the ground, expand and contract as water reserves are stored and used. After a drought-breaking thunderstorm, a shrivelled or limp plant can expand quickly (in the space of days or weeks) to become turgid and more succulent. If there are no following rains in the weeks or months after the initial thunderstorm, then these plants will slowly contract again as the reserves of water are slowly used.

A few plants, like some of the Australian Peperomia species, are very succulent when immature, but develop larger, thinner leaves as the plants age and prepare to flower. These mature leaves may appear so dissimilar as to be from a different species, almost lacking succulence.

Not all plants have the ability to develop succulence. For example, maidenhair ferns, azaleas and roses would shrivel and die under the harsh conditions described above. The ability to develop succulence is restricted to those plants which have a genetic predisposition to do so and this is an evolutionary adaptation. This, coupled with the environmental influences previously mentioned, is required for succulence to develop to any substantial degree and to qualify a plant as a succulent plant, as broadly defined by botanists.

Does Australia have any succulents that are interesting and worthwhile?

In 2006 a common view was still held that there are few succulent plants to be found 'in the outback'.

Almost totally excluded in Australian gardening books and magazines until 2007, this has now changed dramatically. Drought is highlighting the need to consider less water-demanding plants for the house and garden. This goes hand-in-hand with an increasing interest in our own native plants, many of which are still being trialled for their potential to compete with exotic plants in both smaller gardens and larger landscapes. Senior botanists across Australia are currently working on revising and expanding what we know about these previously little known plants. An early insight into what we might expect includes a few new discoveries, lots of new and changed names, as well as opportunities to understand, appreciate and cultivate a greater range of Australian plants than ever before.

An example of a succulent plant that is unappreciated in cultivation is Disphyma crassifolium ssp. clavellatum. This is a mouthful of a name to read let alone pronounce correctly. This plant's common name is far from pleasant either - Pigface, or more correctly Round Leaf Pigface, or sometimes Rounded Noon-flower. With a common name like Pigface, the plant doesn't sound appealing to try and grow at all; however, this widespread native plant is found naturally along much of the south coast and inland areas of low-lying saline soils. It is common in floodplains and is also found in southern Queensland. This plant propagates well from cuttings taken in the cooler months of the year and grows really well in most soils but must be grown in very exposed sunny areas. Its use in home gardens and the landscape are very much in the trial stage.

| |

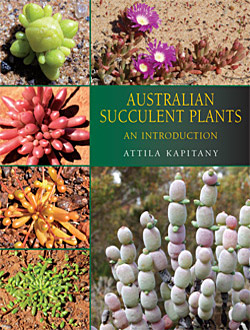

| Australian Succulent Plants: An Introduction |

This stunning book is well set out, extremely colourful and inspirational. The captions on the photographs are informative and clear. The production of this book is a first for this contemporary group of native plants.

|

| A review of Australian Succulent Plants can be found here |

|

As the primary interest in our hobby is a very visual one, what seemed to be lacking on this subject was a clear and straightforward account that also showed photographically what was out there, illustrating the plants in the most aesthetically pleasing way. Books dealing with roses do not show rose bushes out of flower, or focus on their leafless, thorny stems, but on their floral display. Australian succulent plants need a similarly better press, and since 2002, it has been one of my prime objectives to rectify this omission.

Having seen desirable succulent plants in my travels through my native Australia from time-to-time, I longed to share this rich legacy with others. So, along with Michele, my wife, I set out to spend at least four years specifically tracking down, photographing and documenting native Australian succulent plants in habitat. One of the major aims was to illustrate some of the best plants and, importantly, to show them whilst at their best. Being a collector of cacti and succulents for approximately thirty years helped focus my attention on features like flowers, symmetry, seasonal colour changes and specific peculiarities that only a fellow succulentophile would appreciate with a passion, such as the fatter, or fattest stems, exposed tuberous roots or any other odd visual characteristic.

This lengthy period of research culminated in the publication of my latest work, Australian Succulent Plants (2007) which covers approximately one hundred species, including some of the most interesting, rare and unusual plants from forty genera, with most described and illustrated in some detail. There are also additional notes on traditional and modem foods, availability, cultivation, conservation and other items of interest. Included are some of the most under-appreciated, diverse, and interesting Australian plants, including some xerophytic non-succulents. This introductory book about Australian succulent plants provides an inventory of these interesting and intriguing plants, with their remarkable water storage techniques, and hopefully will act as a stimulus for further research and their conservation.

I have for several years now been trialling these plants for suitability in the house and garden with some success. Most gardeners will find it pleasantly surprising that some of these plants grow well in a variety of situations.

Indoors, I have Doryanthes and Peperomia in pots. Outdoors on the veranda are several pots of Anacampseros, Bulbine and Portulaca while in the open garden there is a varied selection of other Australian succulent plants, mostly mixed with all types of exotic succulents to truly reflect a cosmopolitan garden style.

A few pictorial examples are shown in the accompanying photographs. These are simply illustrative of the riches and beauty of what is in fact 'out there', among Australia's succulent plants.

Further information on Australian succulent plants can be found on Attila's website Australian Succulent Plants.

From "Growing Australian", the newsletter of the Australian Plants Society (Victoria), September 2008.

Australian Plants online - 2009

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)

|