Garden Design Principles

Designing With Australian Plants

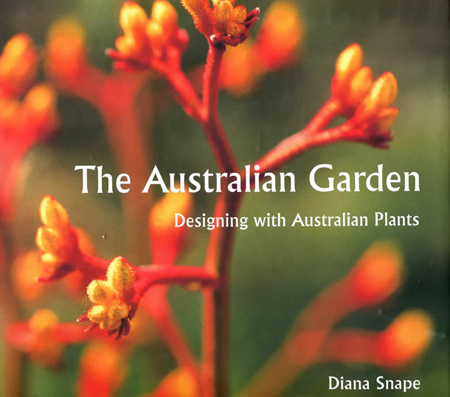

The following is the introduction section from “The Australian Garden: Designing with Australian Plants” by Diana Snape; Diana is a former leader of the Garden Design Study Group. This introduction is reproduced with the permission of the author and publisher.

|

The Australian Garden Designing with Australian Plants 2002 |

Aims and visions

The garden must be prepared in the soul first or else it will not flourish.

Old English proverb

A beautiful garden designed with appropriate Australian plants has many special and appealing qualities. It can be home for a variety of native birds, animals and insects. It can display an array of colours, stunning or subtle, and tantalise with a variety of scents. A garden of Australian plants has practical advantages with modest requirements of resources such as water. Significantly, it has a serenity often hard to find elsewhere.

Before you start planning, it helps to identify your aims and to find an overall vision for your garden that will continue to inspire you. Visiting other gardens, especially local ones, may prompt ideas. Remember your family’s needs may change, just as your aspirations may also evolve as your garden develops. Australians relax, entertain, work and play in their gardens, so the design must suit your lifestyle. A garden can extend the boundaries of a home in a distinctive way, with no hard division between inside and out. Achieving harmony in the total home environment involve good design, centred in simplicity and tailored for you.

A special entrance garden, sunny mounds for flora from arid areas, or sheltered areas for ferns may be among your aims. In hot climates, you may long for the coolness of a shady summer garden with trees, dense planting, rainforest flora and water in a pond or pool. In colder climates, gardeners welcome maximum sunshine or a sunny winter courtyard. You may wish to maintain open sunny areas between swathes of trees and shrubs that, later on, could shelter an array of smaller plants from wind and frost.

What style of garden would you like to achieve? Do you want a hard or soft look, bold use of colour or prevailing shades of green? You may plan your garden for specific local conditions, such as coastal or arid. An informal garden landscape might be easy to maintain and compatible with a growing family, or you may prefer a neat and tidy formal garden. Repeating form and foliage from surrounding natural landscapes will ensure an integrated and harmonious result or you may decide to follow a theme such as foliage or flower colour or interesting textures.

Increasingly Australians look to their garden not just for its beauty but also as a haven, a source of comfort and reassurance. A beautiful garden may soothe a troubled mind or encourage a creative spirit. A living space that respects the environment and its natural cycles can make us feel better mentally and physically – just as we try to provide optimum conditions for the health of our plants, so we can for ourselves. Gardens managed in harmony with nature will be serene with a palpable ‘sense of place’.

Establishing a garden with Australian plants enables a more efficient management of soil, water and energy. If this management is combined with design skills, we can anticipate the development of gardens that function well and enjoy a certain look or style, so that instinctively we say ‘That’s a great Australian garden!’

|

Adams garden Victoria. Designed by Gordon Ford

This special, welcoming entrance area links garden to house and is beautiful to look out on from inside. A timber frame outlines the space where a lily pond provides coolness and humidity in hot weather. A waterfall has been created among skillfully placed rocks. |

Design principles

Gardening calls for an artist’s eye for colour and form coupled with a musician’s sense of developing a theme over time – something the visual artist can’t do.

Kevin Nicolay, quoted in Horticulture, January 1990

Garden design is as much an art form as painting or sculpture. Some gardeners claim it is the highest form of art because plants change with the seasons and the years, so the designer is working in four dimensions. Underlying all art forms are a few basic design principles. Successful garden design depends on the application of these principles, while fulfilling your aims, and responding to the demands of available material (including plants), the site, climate and budget.

There are two main phases in designing a garden. First is the development of your vision of the desired effect, the way you want to use the space. This is the broad design. It involves identifying the roles that plants will play and how they will be arranged to achieve your vision. The second phase involves choosing the actual plants. Then the real joy begins!

|

Hanson garden Victoria. Designed by Bev Hanson

A Bower Vine (Pandorea jasminoides) arches over a pathway, framing the vista beyond. This climber is attractive with large, glossy leaves and pale pink trumpet flowers but requires pruning each year to keep it in shape. |

Scale and proportion

A garden of appropriate scale can enhance the buildings within it – it can emphasise the best features, and disguise or hide poor ones. The house and garden should work as one visually pleasing space. If the surrounding landscape or the building dominates, a garden on too small a scale will look limited and insignificant. Planting of extensive areas should be bold, for example with stands of tall trees and an array of middle- and lower storey plants. In contrast, a large shrub in a small cottage garden is likely to look incongruous and be too dominant.

The size of each component – paths, steps, rocks, pool and seats – should be appropriate for the dimensions of the garden and the house it surrounds. Wide front doors need wide approaches; tall trees look best in large gardens.

There are many ways to solve problems of scale. You can bring a large garden back to human scale by subdividing it into separate spaces, either outdoor ‘rooms’ or less regular areas, each serving a specific function or enjoying different characteristics. If you plan a cottage or wildflower garden as part of a much larger garden, you could contain it with a formal or informal hedge, or a pergola; then the whole becomes a unit within the overall design.

Proportions or ratios will help determine the ‘feel’ of a garden. One significant ratio is between open space at ground level, including paths, and the ground space occupied by garden beds or planted areas. Another is the comparison of space and vegetation at head height, which affects visibility through the garden. A third ratio is that of relative heights of plants – trees, shrubs, groundcovers and tufted plants. Harmonious ratios contribute to the serenity of a garden. For example, is this poa (Tussock Grass) the right size to place next to this rock? The answer will depend on ratios of sizes and ‘your personal response to them – for example, a ratio of one-half or one-quarter may be less pleasing to the eye than one-third (closer to the ‘golden mean’).

Symmetry, asymmetry and harmony

Harmony relies on proportion and symmetry. Formal gardens have symmetry about an axis. Informal or naturalistic gardens are asymmetrical. Both styles require elements to be in pleasing proportion but you can obtain balance about an axis by means other than symmetry. Balance depends on the arrangement of masses and voids, horizontals and verticals, forms protruding and receding. Where balance is aesthetically pleasing, the effect is harmonious. Formal gardens have strong appeal for their obvious balance and order; however, they may suffer from being too predictable. Symmetry often works best on a large scale where there are enough individual features to sustain interest.

An asymmetrical scene that achieves harmony generally intrigues the eye longer, especially in restricted areas. Asymmetry need not be a total absence of symmetry, which may appear as an unsettling and undesirable hotchpotch of plants, but a balance achieved by an equivalence of components. For example, the mass of a dense shrub on one side of a pathway may visually balance a group of more wispy shrubs on the other side; the vertical dimension of a tree on one side might be equivalent to the combined heights of a group of shrubs or a swathe of strap-leaved plants on the other; the ‘negative’ space of a reflective pool may be balanced by sky.

Of course in all gardens (even formal ones) everything grows, at varying rates, and the effect of time is likely to alter proportions and balance, so you need to manage growth to maintain harmony.

Line, shape and form

Line is a primary element in creating shapes and may be used in an infinite number of ways – straight and curved lines, complex patterns of lines. Converging lines may be used to focus inwards, diverging lines to open out. Parallel lines of plants can form a partial screen. Crossing lines can create shapes and patterns. Broad-scale horizontal lines of water, grass and distant low hills produce a tranquil effect. In a small garden, the flat surfaces – water, mulched open space, ground-hugging plants, a mown lawn – contrast with the vertical dimension of strap-leaved or tufted plants such as reeds, lilies, grasses and Kangaroo Paws. Their upright stance reinforces other vertical lines. The white trunks of eucalypts like Lemon-scented Gums (Corymbia citriodora) planted together in a lawn make the statement on a grander scale. Light produces silhouettes of trees and a tracery of shadows of branches as a secondary series of lines. Lines outline surfaces and, in three dimensions, describe regular or abstract shapes.

Shapes or forms come in a limitless variety, hard- or softedged, on their own or in combination with lines and circles. Picture a mountain, a bushy tree, a shrub – you are mostly aware of shape and solidity. The composition of shapes in a garden should sit comfortably within the surfaces and shapes of the surrounding landscape. Some plants are regular in shape – spheres, ellipsoids or cones – but more are irregular and few, other than pruned hedges, have the flat surfaces characteristic of hard landscape. Australian plants display an infinite variety of growth patterns – upright or weeping, rounded or spreading, single or multi-trunked, graceful or sturdy. An ability to relate shapes well will produce visual strength in garden design.

Form is often referred to as the ‘bones’ of a garden and good gardens invariably have ‘good bones’. The form of an individual plant is just the starting point, as you can mass groups of plants to create simple or complex shapes. If the plan calls for a tall thin plant, only one may be needed but a rounded mass could be filled by one large plant or a series of smaller ones. Several similar species may be introduced without disrupting the unity of the overall design. Plants with similar foliage blend into the larger plant mass, while shapes of plants defined by contrasting foliage – in colour, leaf shape or size – stand out from the overall form.

Another element could be dots or circles, as in traditional Aboriginal artwork or the landscape itself – all sizes of rounded pebbles or rocks, plants or groups of plants.

|

Davidson garden Victoria

In a coastal garden, rounded forms of correas such as White Correa (C.alba), grevilleas and taller banksias are massed to create a pleasing overall form in the landscape. |

Masses and voids

The question of balance between material and space, or mass and void, must also be considered. What the eye sees as open space depends partly on the scale of the garden. In large gardens, you see space between groups of trees or shrubs; in a rainforest garden you see beneath the canopy and along paths; in intimate town gardens the space between individual plants is more significant. Whatever the size of the garden, space is the counterpart of the solid masses of vegetation. A pleasing balance between material and space and the shapes so created is essential to achieve harmony A fence or wall gives space a straight edge, while the convex surface of a shrub gives space a concave side. Open space provides a natural setting – a stage – for a feature plant, garden furniture or sculpture.

Many conventional gardens, with their high proportion of open space and relatively narrow garden beds around the margins, do not inspire. At the other extreme, a garden with no open areas looks overcrowded and cluttered. Without open space there are no views, from within either the house or the garden. Gaps between foliage allow you to observe framed vistas, providing visual links between separate parts of the garden and giving a sense of space. The appropriate balance between material and space will be determined by the type of garden, sheltered and intimate or expansive and open, and the plants you choose. It is amazingly easy to over-plant and have open spaces shrink as plants grow, though this is part of the natural development of any garden. Pruning and replacement can maintain the desired balance.

Unity and repetition

Your personal touch will help ensure unity in your garden, especially as you develop firm ideas about design and the confidence to follow them. The strong appeal of a formal garden lies in its unified order. In a naturalistic garden, repetition is just as important but the rhythms are more subtle.

While you may choose to treat various areas differently, links will assist in creating unity. A gardener can enhance harmony by repeating some elements from space to space, for example the form and texture of a particular indigenous eucalyptus or leptospermum (Tea-tree) species; of groundcover plants, rushes, sedges or grasses; or of the material used for hard surfaces. You might use border plants to link one site to the next. Too much repetition of elements can be monotonous but the complete lack of it creates disharmony, which might be exciting but is difficult to live with.

Focal points and framing

Focal points to draw the eye are valuable features to include in a garden. In a large landscape a focal point could be a sculpture or feature tree; in a small intimate garden a moss-covered rock or beautiful plant in a pot. Items appropriate for formal gardens will differ in style from those for naturalistic ones. In a formal setting, avenues, hedges or sculpture may lead the eye to a focal point; in a naturalistic one the gardener can use more subtle elements, perhaps silvery or other distinctive foliage. If you create one major focal point in any one vista you will enjoy these highlights as you move through the garden.

Every picture is enhanced by a frame that encourages the eye to focus on the composition. Frames are straightforward in formal gardens – an arch, a wall or a solid background of dark-green foliage. ‘Doors’ or ‘windows’ cut into a screen increase interest as you glimpse framed views of another part of the garden. Chinese and Japanese gardeners effectively use Moon Gates, circular openings onto a view beyond. In a naturalistic garden, focal points should be less dramatic as gardens are viewed from different angles. There is less scope for formal framing but a uniform green background will highlight any feature plant. Natural-looking frames can be created with skilful pruning. If you are lucky enough to have dramatic scenery, such as mountains, as a backdrop, you may enhance the view by carefully framing it with trunks or foliage.

Screening

If your garden is without mystery and all can be seen at first glance, it may soon lack interest. Consider subdividing a large garden into separate compartments, each with its own character. Partial screens can allow glimpses of what is beyond while obscuring the details, enticing you to explore further. Discovering the whole garden, section by section, is a gradual and exciting process. Screening can also work in small gardens so that we feel enfolded by nature. It can make small gardens feel larger and more remote from the noise of city life and nearby vehicles.

Choosing the essentials

Gardeners need to be discriminating, to choose the essentials and not try to pack everything in. This discrimination and the ruthlessness needed to exercise it develop with experience, so don’t ever feel guilty about your mistakes, just learn from them. As the renowned garden designer Gertrude Jekyll put it: ‘The way to enjoy beautiful things is to see one picture at a time, not to confuse the mind with a jumble of too many interesting individuals’. Elsewhere she wrote: ‘In all kinds of gardening … the very best effects are made by the simplest means’. Jekyll, writing in Victorian England, also believed strongly in the use of local (indigenous) plants and her message of simplicity is equally valid today.

|

Hanson garden Victoria. Designed by Bev Hanson

On either side of a path, planting is asymmetrical but harmony is achieved by a satisfying balance. Tufted plants include a fine lepidosperma and groundcovers such as Creeping Myoporum (M. parvifolium) in the foreground, adding variety to taller shrubs behind. Rounded forms, colours and particular species are repeated and the planting near rocks is of appropriate scale. In bloom on the left are two grafted darwinias, D. meeboldii and, in front, D. macrostegia (Mondurup Bell) with spectacular red and white streaked flowers. |

|

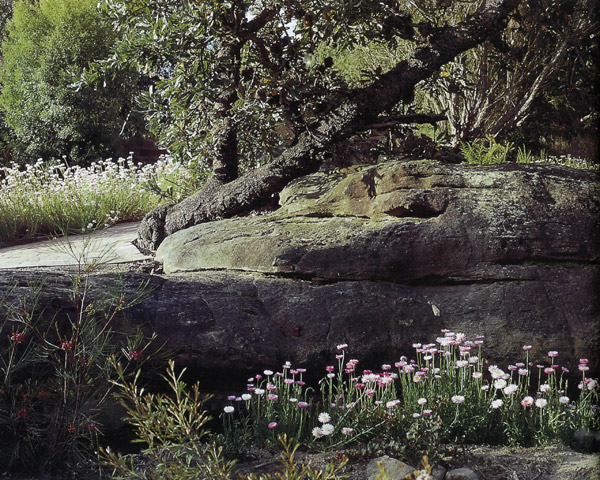

John Hunt’s garden New South Wales

A Mud sandstone shelf and an old, gnarled Banksia serrata (Saw Banksia) have been retained on the site and contribute great character to the garden. Massed annual Rhodanthe chlorocephala ssp rosea (Pink Paper-daisy) add contrasting colour and delicacy against the background of solid rock. |

Knowing the Site

Unlike the weather, soil can be improved.

Hugh Johnson, Hugh Johnson’s Gardening Companion, 1966

Garden design must respect the existing site conditions.

Topography and soil

Is the land flat, sloping slightly or steeply, or irregular and interesting with higher and lower areas? Whatever the surface and its contours, they can be manipulated. The characteristics of surrounding landorms may also influence design.

Soil provides the foundation for the garden and much will depend on its nature – whether it is a product of alluvial deposition or the underlying geology and rock character. For a plant to reach its full potential the roots must be healthy, without disease or stress. Both sandy and clay soils have their advantages but a wide range of Australian plants prefer sandy loam because of its intermediate particle size. Although it may be tempting to bring in soil from elsewhere to ‘improve’ poor soil, this is generally not a good idea. It is preferable to improve existing soils by, for example, adding gypsum to heavy clay to improve the texture.

Some plants can grow in a range of areas and the occasional experiment can be worthwhile. Alkaline soils are more restrictive than acid, as generally plants from alkaline areas will grow in more acid conditions but the reverse does not apply The situation in which a plant normally grows provides valuable guidelines – those found on ridge tops generally demand good drainage but also put down deep roots to endure drought. Plants from valley floors where water lies longer after rain are usually more shallow-rooted and susceptible to drought, while periodically tolerant of water around the roots. Ridge-top plants are also more likely to be frost-tender than their valley neighbours, because cold air drains downhill.

Water and climate

Water and climate will also restrict the choice of plants from other areas of Australia that will grow well for you. Rainwater is a precious resource that you should aim to retain in your garden wherever possible. Early in your observations you will quickly determine the directions and force of prevailing winds so that you can position important windbreaks to shelter the house and later plantings. A double row, not too dense, can be very effective. Consider wind deflection and local breezes. Plants may be sensitive to heat or frosts (especially when conditions are dry), so try to identify frost pockets. Observe the movement of the sun as it changes throughout the year. Consider the orientation of the garden and the resulting light patterns, as they will determine how growing trees and large shrubs change the distribution of shade.

‘Borrowed’ landscape

If you look out to wide open spaces or attractive suburban gardens, you may want to enjoy your ‘borrowed’ landscape and restrict planting to low shrubs, tufted plants, or trees with an array of splendid trunks to frame the view. If the outlook is less appealing, a formal or informal hedge of shrubs can block the sight and create an enclosed area that is sheltered and cosy.

Starting with a block of land

Even a bare block of land has a history that may influence your options. It may have been used for grazing, an orchard or market garden, a sanitary land-fill, or a pine forest now burnt. Weeds, temporary or persistent, sometimes tell the story. They are best tackled early. A weed-infested area may eventually become the most prolific garden bed! Building a house, even with minimum disturbance, will also affect the distribution of soil and water on the block.

Starting with a house and an existing garden

Look at the house from many points in the garden. The style of house does not predetermine the style of garden, though the lines and mass of the building should certainly be taken into account. Check views from your windows too and identify those you want to retain, rescue or hide. The forms, textures and colours of plants and their combinations should create a picture in harmony with the building, or be designed to contrast.

Renovating an existing garden provides an excellent opportunity to remove unhealthy plants or those in the wrong position. (It’s less painful when you haven’t planted them yourself!) It’s easier to design on a clear canvas but established plants, if suitable, will provide the ‘backbone’ for any new garden. Inheriting a well-established garden has its blessings. First, there is less urgency to get started. You have time to consider the strengths and weaknesses of the existing design and plantings, which may tell you a lot about the site and its features. Secondly, you can create a new garden ‘inside’ one that is many years old. But an existing garden can often tempt the designer to compromise, as it can be difficult to see the garden with new eyes and not be strongly influenced by what is already there.

A ‘bush’ block

A block of natural vegetation may include trees, shrubs, groundcover plants, strap-leaved plants and grasses that could all contribute to a beautiful natural garden. The importance of such local indigenous plants is discussed later. The less land is cleared, the more unspoilt (and maintenance-free) the natural garden will be. If this area is large enough to be sustainable, eight hectares or so, in some states it can be protected forever by a covenant. Covenants originated in Victoria in 1972 with the Trust for Nature and more recently have become available in some other states.

The nature of the ‘bush’ will influence decisions. Grassland or heathland provides a wonderful open garden if disturbed as little as possible. Woodlands with large trees are shaded and enclosed, so you may have to remove some trees to obtain space and sunlight for the garden as well as buildings. Such clearing will affect local wildlife. The ecology of the site depends on the types and sizes of plants present and how they associate with each other. Look for evidence of animal life, remembering that it may be seasonal. Try to identify dominant plant and animal communities, their dependence on the existing conditions and their sensitivity to change.

A ‘bush’ block, or one next to a National or State Park or other conservation area, provides a ready-made, natural garden into which your garden can flow. Avoid using plants that can ‘escape’ and become weeds, either exotic plants or Australian plants from other areas. The attractive Acacia baileyana (Cootamundra Wattle), which occurs naturally in a very restricted area near Cootamundra, NSW self-sows abundantly and flourishes in many parts of Australia where it has been introduced. It is an example of an Australian plant now considered a pest. So check on potential nuisances before you plant and become attached to them.

Another responsibility for pet owners, particularly of cats, is not to allow them to wander at any time. Cats can be devastating killers of birds and other wildlife.

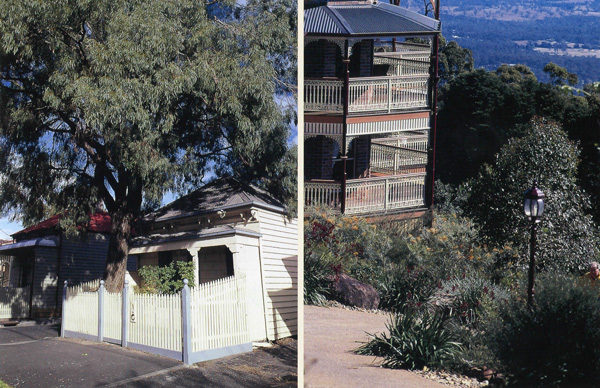

LEFT: Terrace garden Victoria Bought in the 1960s as Eucalyptus nicholii (Willow Peppermint) and supposed in RIGHT: Webb garden Qld A Steep site reveals an expansive borrowed landscape. A garden of Australian plants |

Making a Plan

You have to have an ideas. If you don’t have a concept, you’re just making goulash.

William Brincka, quoted in Horticulture, May 1990

Beginning a new garden or re-working an old one can seem a challenging task. The secret is to decide first on an overall broad-scale plan, without worrying about all the details. Set your priorities, then implement the plan in stages, taking one step at a time.

At an early stage, decide how much time you want to spend maintaining your garden. Both the style of garden and your standard of maintenance will affect this decision.

Determine whether you will need walls, fences, a driveway, access to the rear of the block, paths to doorways, steps or paving – all items of ‘hard landscape’. These need to be completed early, so you are ready for the first rain and not surrounded by a sea of mud. Do you want areas for specific uses or activities (for example sitting, children’s play, swimming pool, barbecue, clothes drying)? The initial layout of a garden should provide for such areas, connected by paths linked to the house.

The introduction of large rocks is much easier prior to planting. If you need to use machines to create major changes in ground level, try to do so early in the process. Also at the planning stage it is worth deciding whether you can harvest water in low-lying areas or if you wish to create any features with water.

Planting trees is another priority as windbreaks and screens take several years to be effective and, until trees are above head height, a garden will appear young and unfinished.

Another consideration is the extent and shape of open areas and the surfacing or types of plants you’ll choose for them. Mowing grass keeps an area tidy and useable while your ideas change and evolve – grass can be replaced without too much effort at a later stage.

Envisage a plan for the positions and shapes of garden beds and planted areas. Consider proportions and balance, vistas and screening. Design for an attractive arrangement of foreground, midground and background views. Then develop one area at a time, probably starting close to the house and relating each new section to the last. This will save time and energy. It is worthwhile measuring sizes and drawing a sketch plan of individual areas even if you can’t manage this for the whole garden. If you plant all or most plants in one area at the same time, you will find that area easy to look after and the plants will have an equal share of rain and sun.

When you have finished planting one area, relax and enjoy what you have accomplished before starting the next.

|

Hall garden New South Wales

A treehouse in Eucalyptus haemastoma (Scribbly Gum) offers adventure for a growing family. The surrounding lawn provides space to play and, as needs change, the owner plans to extend the mulched garden to gradually reduce or eventually replace the lawn. |

|

Royal Botanic Gardens, Mount Annan New South Wales. Designed by Peter Cuneo

Multiple plantings of the Paper Daisies Rhodanthe chlorocephala ssp rosea (pink), Schoenia filifolia ssp subulifolia (yellow) and Rhodenthe manglesii (white) build these very small plants into large and significant components of the landscape. |

Putting it on paper

Begin your garden planning by applying design principles to the hard landscape, the garden layout, then types, sizes and forms of plants, before thinking about he actual plant species. What will you require in terms of trees and/or large shrubs for the boundaries, groundcover plants, and different plants to suit the varying microclimates in your garden? The choice of species to fill niches will come much later.

A second approach is to select the plants you would like to enjoy in the garden, trying not to include too many ‘impulse buys’ of numerous irresistible offerings, and prepare a detailed list; sort them into various categories (trees, large shrubs, ground-covers); then work out the conditions they require in terms of soil, sunlight, temperature and water, how these can be provided and how the plants can all be arranged into a garden. This can be more difiicult than it seems!

Most gardeners probably combine these two approaches. Drawing (or just sketching) a plan can help immensely whether you are working on a whole garden, a single bed, or redesigning an area. If you plot the spread of plants fairly accurately, according to size guidelines in handbooks or reference books, the spacing will be more correct than if you just guess. A sketch will indicate which plants may be too big for a small garden – often hard to believe while they are still tiny plants. Moving large Australian plants usually kills them, so it pays to plan well.

Design concept

Line is the first element in design. Take into account the shapes in your setting. You might decide on a quite formal layout of garden beds with straight lines, circles and squares carefully measured and arranged in symmetrical fashion. For a more informal design, you can lay out a long hose to establish pleasing shapes for edges of areas you plan to plant. You can be adventurous and start a garden design with an abstract design concept – like the painter Klee, you can ‘take a line for a walk’, not in a painting but on your garden plan. Perhaps experiment with a freehand drawing of cross-hatched or swirling lines on paper, or clusters of shapes, and then simplify it to a satisfying layout pattern.

Sketching bubble diagrams

Start with a plan of your block on tracing paper, showing the position of the house and other structures, including neighbouring houses. Bubble diagrams are an easy way to sketch general areas and their possible uses. Initial measurements can be rough – pacing distances to find approximate lengths in metres. Rough sketches on layers of tracing paper will increase your confidence. These early drawings can be overlaid, analysed and refined until you and the family are happy. You can then begin to design the site in detail, including the planting plan.

Photographs both within the garden and from outside can be extremely useful. Plot on the plan where these photographs are taken.

|

A bubble diagram is an easy way to begin, sketching general areas and their possible uses. |

|

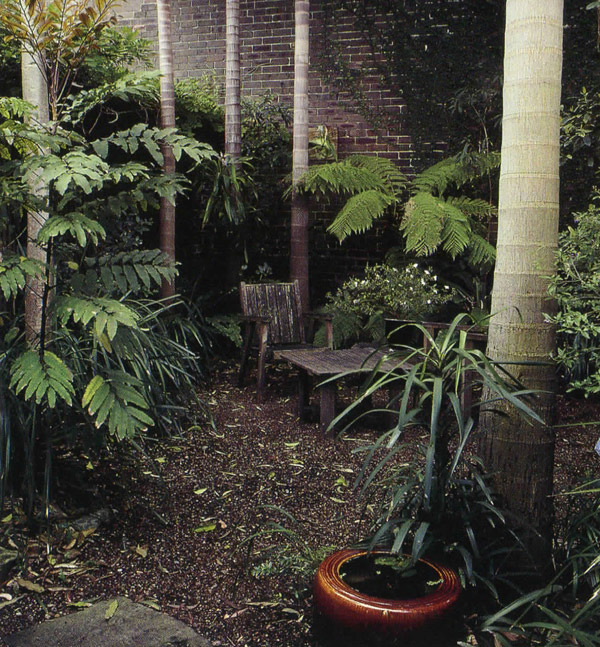

Rowland garden New South Wales. Designed by Gordon Rowland

A tall wall becomes a splendid backdrop and its height is scaled down by a group of architectural Bangalow Palms (Archontophoenix cunninghamiana) and attractive plants with foliage interest such as Black Wattle (Callicoma serratifolia) and Long-leaved Tuckeroo (Cupaniopsis newmanii). |

Plants on the plan

A plan can become a record of your plants and their situation in the garden. Show positions of tree trunks and the extent of their canopy and those from trees next door. Note any spectacular plants -a few of these will create drama, but do not crowd them together. Star performers need quiet companions to show them off. Remember that the best overall effect is one of simplicity, even though it may consist of dozens of interesting plants. Look at massing plants and creating layers of foliage. Where space will allow, plants generally look better planted in groups of odd numbers rather than dotted about singly or in pairs.

Avoiding mistakes

Mistakes made on paper are much easier and less costly to correct than those made on the ground, Your plan may help you respond to the following warnings.

- Don’t divide up your block in a complicated and fussy way.

- Make sure differences in ground level are visually significant, not just liable to trip you.

- Be careful that repetition doesn’t become tedious; for example, plants of distinct form (such as small conifers) just scattered throughout a garden.

- Avoid straight lines unless In a very formal garden – but also avoid sinuous wavy edges to garden borders, especially exaggerated by a stark outline of broken rocks, unsoftened by plants.

- Make sure arches and pairs of plants to frame views look or lead somewhere in particular.

- Avoid losing valuable views by choosing plants that grow too large.

- Don’t create a fire hazard in fire-prone areas, especially close to the house.

- Check positions and eventual sizes of plants near windows and adjacent to paths.

- Plant some prickly bushes to cater for wildlife but not right beside pathways.

- Don’t plant ferns on mounds or place ponds on the high side of the garden.

- On the other hand, if your instinct is good and you have confidence in it, as Andrew Pfeiffer, landscape architect, says: ‘Almost any rule that you care to devise about the design of gardens is capable of being deliberately broken with dazzling success

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)