Environmental Weeds in Australia

Over the past 200+ years, many plants have become weeds in the natural environment. This not only includes plants from other parts of the world but many Australian native plants as well. The spread of environmental weeds not only destroys native plant communities, it can also result in the possible extinction of threatened native species, both plants and animals.

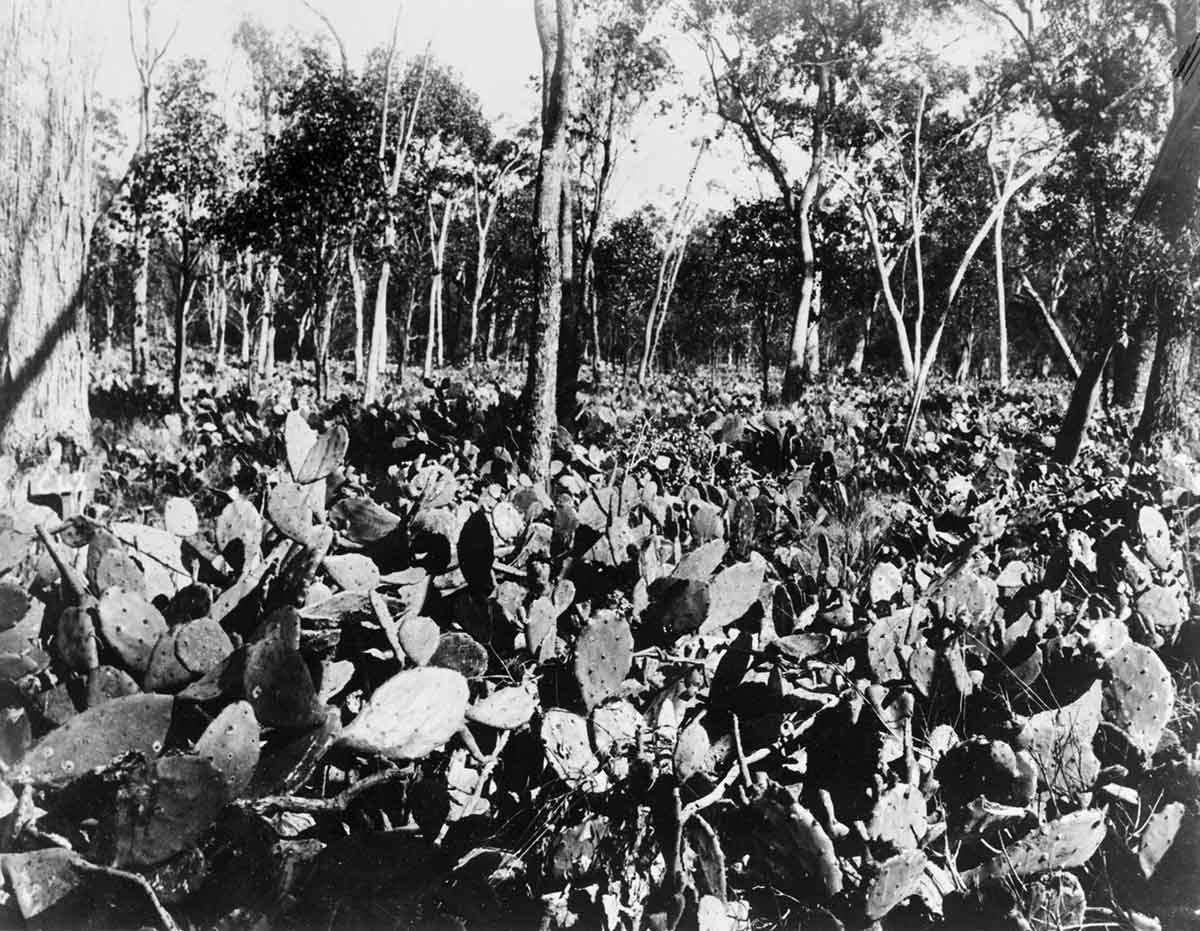

Photo: Prickly pear before the cactoblastis beetle attack, Chinchilla district, Queensland

Header Photo: Bitou Bush/Boneseed – Chrysanthemoides monilifera

Are we serious?

Is an organisation whose objective is to encourage the cultivation of Australian plants really suggesting that people should NOT grow those plants? Well….yes! Under certain circumstances.

It’s regrettable that horticulture, forestry and agriculture have been responsible for many environmental disasters resulting from plants escaping from cultivation and invading natural ecosystems. Everyone has seen the problems that exotic weed species can cause. A few well known examples are:

- Prickly pear (Optunia sp.) – native to north and central America – devestated thousands of hectares of eastern Australia in the early 1900s until successfully controlled by biological means.

- Boneseed and bitou bush (Chrysanthemoides monilifera) from South Africa were used for sand dune stabilisation in eastern Australia and have spread rapidly well beyond coastal areas, replacing entire ecosystems.

- Fireweed, Senecio madagascariensis, (South Africa) has become a serious pest of pasture lands in New South Wales and is also spreading into Queensland. It is a prolific seeder….25,000 to 30,000 seeds per plant with almost 100% germination rate.

But some Australian native plants can also be problem species, both within Australia and overseas. For example:

- Melaleuca quinquenervia (native to eastern Australia and New Guinea) has grown uncontrolled in the Florida Everglades to the exclusion of native species.

- Acacia saligna, A.cyclops, A.melanoxylon, A.mearnsii, and A.decurrens (all Australian natives) are causing serious environmental problems in the South African “fynbos”.

- Examples of Australian native species that have become weedy in certain areas of Australia, usually away from their natural habitats, include:

- Numerous acacias such as Acacia paradoxa which been reported as being a problem in parts of Victoria, and the popular garden wattles Cootamundra wattle (A.baileyana), Queensland silver wattle (A.podalyriifolia) and golden wreath wattle (A.saligna). These are weeds of the Sydney bush and other areas and should not be planted in gardens in the vicinity of natural bushland.

- Melaleuca hypericifolia, native to coastal New South Wales, has invaded natural bushland along the south coast of Victoria.

- Pittosporum undulatum colonises moist areas, such as gullies, and areas of disturbed soil. It grows rapidly and quickly shades out most other plants. The plant seems to adapt to soils with higher nutrient levels much more readily than other native species, hence grows well in areas where the soil has been changed this way.

- Billardiera heterophylla, native to south Western Australia, has become a serious pest in bushland in the eastern states, particularly in Victoria and Tasmania.

- Other native species have proved to be opportunist by flourishing in the changed environment when original vegetation is cleared for pasture or agriculture (eg. sheep’s burr, Acaena agnipila).

……and there are many, many more.

Unfortunately, plants which have become weeds sometimes continue to be sold for garden use in the areas affected.

So while we are certainly not suggesting that people should not plant Australian plants, we don’t have a policy of “Plant Australian at any cost”. We don’t want to be responsible for the further spread of existing “ugly Australians” or for the introduction of new weedy species. The information on this page outlines some of the problems that have occurred, some specific plants that have been known to cause problems in certain areas and suggests caution when considering the cultivation of a species which has not been tried in the particular area before.

This caution, by the way, applies to ANY new “exotic” plant whether from Australia or anywhere else.

Plants growing in their natural habitat have evolved in association with a range of other organisms…other plants, fungi, insects, birds, micoorganisms…they are part of a balanced ecosystem which exerts controls on the growth and development of the plants. Those controls may limit the rate of growth of a plant and its reproduction in a number of ways. Fire may routinely destroy parts of the ecosystem, requiring the plants to regularly re-establish; insects, bird and animals may eat a large portion of the seed; insects may damage the plants so that much of the plant’s energy goes into repair of damaged tissues.

When a plant is taken to some other geographical area, whether within the same country or overseas, all or part of those other components of the ecosystem will almost certainly not be present. Under such circumstances, plants may grow more vigorously and spread more rapidly than they can in their natural environment. If they escape from cultivation, mainly through seeds being spread by wind, by birds or by gardeners disposing of garden wastes in bushland (or on land which drains to bushland), they are potential pest species. The development from a potential pest to an actual pest may take many years to occur or it may never occur. Unfortunately, if a plant does become a pest species, by the time the threat is recognised it is often difficult to develop effective control strategies.

Photo: Brian Walters

In their natural habitat, species in the “Black Wattle” group such as Acacia parramattensis are subject to attack by borers. Without this control, this and other species have become weeds overseas.

Of course, most exotic plant species do not become weeds. People all over the world cultivate plants from all parts of the globe and it is relatively few that end up causing problems. Other controls such as climate and soils may restrict their growth. But the potential for problems is there.

Are Australian plants any different to plants native to other parts of the world in their potential to be weedy?

There’s no reason why they should be, but introducing any untried plant into a new environment always involves an element of risk, no matter where the plant originated. To minimize the possibility of YOU being responsible for the introduction or spread of a weed, perhaps the following suggestions could be considered:

- Grow indigenous plants. These are plants native to your particular geographical area but, unfortunately, it’s not always easy to obtain these plants from nurseries….you may need to seek out local revegetation groups or grow the plants yourself.

- Grow plants that are well established in the horticultural trade in your area. These are likely (but not certain) to have proven themselves non-invasive.

- Become familiar with weed lists for your local area and avoid any plants listed (just because they are listed does not necessarily mean they won’t be available from a nursery). These lists may not always be available but a check with a local agricultural department or local government authority may be useful.

- If you plan to grow a species not normally cultivated in your area (eg. by importing seed from Australia or elsewhere), check with a local botanic gardens, agricultural department, weed control council, National Parks Authority or botanical faculty at a University as to the potential for the species to become invasive.

- If you’re satisfied that there is minimal threat and go ahead and cultivate a new plant in your district (particularly if the garden is near natural bushland), keep it under observation. If it looks like it may become rampant through suckering or prolific seed formation and germination, be ruthless!

- If in any doubt….DON’T PLANT! It’s not worth the risk!

Australian Weed Species

The following has been compiled from several sources and is by no means complete. If you know of other examples, please let us know. Please note that the listing of a species does not mean that it or related species are weeds generally. For example, Melaleuca quinquenervia is a very serious pest of the Florida Everglades but, as far as is known, it has not been recorded as causing problems elsewhere. However, it may be risky to plant the species in similar conditions (ie. tropical wetlands) outside of Australia.

|

Species

|

Common Name

|

Origin*

|

Areas Affected*

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Acacia alata

|

Winged wattle

|

South-west WA

|

South-east NSW

|

|

Acacia auriculiformis

|

Wattle

|

Tropical Australia

|

Florida, USA

|

|

Cootamundra wattle

|

South-western slopes, New South Wales

|

SA, Tas, Vic, WA (south-west)

|

|

|

Acacia dealbata

|

Silver wattle

|

NSW

|

South-west WA

|

|

Acacia decurrens

|

Green wattle

|

South-east Australia

|

South-west WA

|

|

Acacia dunnii

|

Elephant ear wattle

|

Northern Territory, WA

|

North Qld

|

|

Acacia elata

|

Cedar wattle

|

South-east NSW

|

Vic, south-west WA

|

|

Acacia floribunda

|

White sallow wattle

|

South-east NSW

|

Vic

|

|

Acacia iteaphylla

|

Flinders Range wattle

|

SA (north of Adelaide)

|

Vic, south-west WA

|

|

Sydney golden wattle

|

Qld,NSW, Vic, SA, Tas

|

South-west Vic, Inland areas of SA, south-west WA

|

|

|

Acacia melanoxylon

|

Blackwood

|

Tas

|

South-east NSW, south-west WA

|

|

Acacia paradoxa

|

Kangaroo thorn

|

All states

|

Vic and parts of inland NSW

|

|

Queensland silver wattle

|

Qld between Brisbane and Rockhampton and central inland

|

South-east Qld, NSW, south-west WA

|

|

|

Golden wattle

|

SA

|

South-west WA

|

|

|

Acacia saligna

|

Golden wreath wattle

|

South-west WA

|

SA, Vic, south-east NSW, South Africa

|

|

Acaena agnipila

|

Sheep’s burr

|

Australia

|

All states

|

|

Billardiera heterophylla

(syn. Sollya heterophylla) (1) |

Western Australian bluebell creeper

|

Western Australia

|

NSW, SA, Tas, Vic

|

|

Cassinia arcuata

|

Chinese shrub

|

Australia

|

NSW, Qld, SA

|

|

Casuarina cunninghamii

|

Australian pine**

|

Eastern Australia

|

Florida, USA

|

|

Casuarina equisetifolia

|

She oak

|

Eastern Australia

|

Florida, USA

|

|

Casuarina glauca

|

She oak

|

South-eastern Australia

|

SA, Florida, USA

|

|

Corymbia torelliana

|

Cadaghi

|

North Queensland

|

South-east Queensland

|

|

Cupaniopsis anacardioides

|

Carrotwood**

|

Qld, NSW, NT

|

Florida, USA

|

|

Tasmanian blue gum

|

Tasmania, southern Victoria, NSW

|

WA, California, USA

|

|

|

Eucalyptus saligna

|

Sydney blue gum

|

NSW

|

WA

|

|

Hakea sericea

|

Silky hakea

|

NSW, Victoria

|

South Africa

|

|

Hakea drupacea

(syn.H.suaveolens) |

Sweet hakea

|

Western Australia

|

South Africa

|

|

Coastal tea tree

Australian myrtle** |

NSW, Vic,Tas

|

SA, NSW, south-west WA, South Africa

|

|

|

Punk tree**

|

Eastern Australia, New Guinea

|

Florida, USA

|

|

|

Nephrolepis cordifolia

|

Fish bone fern

|

NSW

|

Qld, Vic, WA

|

|

Paraserianthes lophantha

|

Cape wattle

|

WA

|

NSW, SA, Tas, Vic

|

|

Pennisetum alopecuroides

|

Swamp foxtail

|

Coastal NSW, although this is dubious

|

Qld, SA, WA

|

|

Sweet pittosporum

|

Qld, NSW, Tas, Vic

|

NSW (east), SA, Vic, Cuba

|

|

|

Umbrella tree

|

Nth.Qld, NT

|

Florida, USA; NSW, Sth.Qld

|

|

|

Sclerolaena birchii

|

Galvanized burr

|

Australia

|

Semi-arid NSW and Qld

|

|

Sclerolaena muricata

|

Black roly poly

|

Australia

|

Semi-arid eastern Australia

|

|

Solanum hoplopetalum

|

Afghan thistle

|

Western Australia

|

South-west Western Australia, South Australia

|

|

Magenta cherry

|

North coast NSW

|

South-east NSW

|

* NSW=New South Wales; NT=Northern Territory; Qld=Queensland; Tas=Tasmania; Vic=Victoria; SA=South Australia; WA=Western Australia.

** Common name in the country where the species is a pest.

1. In South Australia, Billardiera heterophylla is now a declared weed species that must be controlled – it is banned from sale in that State

Exotic Weeds in Australia

The following has been compiled from several sources and is not intended to be comprehensive. For details on these and other weeds of Australia, refer to the ‘Further Information’ section.

|

Species

|

Common Name

|

Origin*

|

Areas Affected*

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Andredera cordifolia

|

Madeira vine

|

South America

|

Qld, NSW

|

|

Araujia hortorum

|

Mothplant

|

South America

|

Eastern Australia

|

|

Bryophyllum delagoense

|

Mother of Millions

|

Madagascar

|

Eastern Australia

|

|

Carduus nutans ssp.nutans

|

Nodding thistle

|

Europe, Asia

|

NSW, Vic, Tas, WA

|

|

Bitou bush

|

South Africa

|

Eastern Australia

|

|

|

Chrysanthemoides monilifera var. rotundata

|

Boneseed

|

South Africa

|

Eastern and southern Australia

|

|

Cinnamomum camphora

|

Camphor laurel

|

China, Japan

|

Qld, NSW

|

|

Cyperus rotundus

|

Nut grass

|

Africa, Asia

|

Qld, NSW, Vic, SA, WA, NT

|

|

Echium plantagineum

|

Paterson’s curse**

|

Europe

|

Australia (widespread)

|

|

Ipomoea indica

|

Morning glory

|

Tropics

|

Qld, NSW

|

|

Lantana camara

|

Lantana

|

The Americas

|

NT, Qld, NSW

|

|

Mesembryanthemum crystallinum

|

Ice plant

|

South Africa

|

Southern Australia

|

|

Opuntia stricta

Photo from Wikimedia Commons by Peripitus, reproduced under the Attribution ShareAlike 3.0 License |

Prickly pear***

|

Central America

|

Widespread, particularly eastern Australia

|

|

Ricinus communis

|

Castor oil plant

|

Asia, Africa

|

Australia (widespread)

|

|

Rubus fruticosus

|

Blackberry

|

Europe

|

Australia (widespread)

|

|

Fireweed

|

South Africa

|

NSW

|

|

|

Solanum elaeagnifolium

|

Silver leaf nightshade; white horsenettle

|

Southern Americas

|

South Australia, Victoria

|

|

Ulex europaeus

|

Gorse

|

Europe

|

Mainly Tas, Vic; also NSW

|

|

Vachellia farnesiana

(syn. Acacia farnesiana) |

Mimosa bush

|

Cosmopolitan

|

Qld, NSW

|

|

Xanthium spinosum

|

Bathurst burr

|

South America

|

Australia (widespread)

|

* NSW=New South Wales; NT=Northern Territory; Qld=Queensland; Tas=Tasmania; Vic=Victoria; SA=South Australia; WA=Western Australia.

** In dry areas it is called “Salvation Jane” as it may sometimes be the only available feed for livestock.

*** Several Optunia species were weeds but O.stricta was the most serious. Its control is probably the most famous example of biological control in Australia. The species spread dramatically in the early 1900s and covered millions of hectares. It was brought under control by the caterpillar Cactoblastis cactorum. Prickly pear is still widespread in all mainland Australian states but it is not the pest it once was.

Restoration of degraded areas of natural vegetation is a daunting task that often defeats the resolve of even the most dedicated environmentalist. A method that has become popular in New South Wales, particularly, is the “Bradley Method of Bush Regeneration”. This has proven to be extremely effective and has been taken up by both government agencies and community groups. Its main drawback is that it requires patience; immediate gratification cannot be expected.

The method was developed by sisters Eileen and Joan Bradley and is based on allowing the native plants to re-colonise areas following, mainly, hand clearing of weeds. The following article from the December 1983 issue of “Native Plants for New South Wales” (newsletter of the Society’s NSW Region) outlines the basic methodology. The methods have not changed appreciably over the years and still produce outstanding results.

Regeneration of the Bush

Based on a lecture by Evelyn Hickey to the Society’s North Shore Group

The names Eileen and Joan Bradley are of course synonymous with bush regeneration. These pioneers came from a family of scientists and they themselves followed that tradition in an era when women were not generally accepted in that field. It is not surprising therefore that they turned out to be the persevering ladies they were. They were employed by the National Trust in 1976 to train workers in their techniques to work at the Blackwood Sanctuary.

They started out with 3 people! The Trust now employs 75 workers, advising 13 municipalities, governments and private concerns, and is constantly training new recruits — quite a success you might say.

|

| Cartoon by Alan Stevenson |

The Mystery of the Method

The greatest mystery of the whole Bradley method is that no-one knows why it works — it just does! Its advantages are:

- It works

- It is economically sound

- It encourages a more diverse plant community to establish itself.

Its disadvantages are:

- It requires skilled workers

- It takes a long time

- There is only a subtle change — no dramatic changes occur.

Basic Principles

To quote from the National Trust pamphlet on the Bradley method, the basic principles are:

- Work from the least weed infested areas to the most densely infested. In the least infested areas there are abundant native plants and seed to colonise the area from which weeds have been removed. In the dense weed infestations, the number of weed propagules far out number native propagules so weed growth rather than native plant growth is favoured.

- Minimise soil disturbance. This includes replacing top soil in its correct position so that the stored seed is not buried too deeply and keeping the soil deeply mulched.

- Allow native plant regeneration to dictate the rate of weed removal. Native plants which regenerate must be allowed to form a dense and healthy group before the adjoining weeds are removed. These natives can then successfully colonise the newly weeded area. If too large an area is cleared before native plants are capable of colonising it (over-clearing), weeds will successfully compete with native plants.

The Temptation

It is tempting to make a spectacular effort and remove an eye-sore of introduced plants from along a track or creek. This leaves the area open to the regrowth of more of the same type of seedlings and, worse, the introduction of quick-growing, free-seeding introduced plants. These work their way deeper into the bush and widen the weed boundary. Further effort spent on the removal of these plants simply compounds the mistakes.

If, on the other hand, the bush behind the weed-barrier is strengthened, work can be carried out on the basis of working from good to bad and specific areas of introduced plants can be removed so that the strong bush can move in to replace them. It is all very subtle and requires a great deal of patience. By tipping the balance of power towards the natives, weeds will be inhibited and finally eliminated so that very little attention need be given to the area …possibly a follow-up once every year or two.

The disadvantages are mostly those of human impatience. The method cannot proceed faster than the native plants regenerate. One should not expect the bush to return to a weed free state overnight as it has taken many years to reach the weed infested state.

An example is the “Wingham Brush” — an area of rainforest on the north coast of New South Wales. It is estimated that it will take 20 years to return the Brush to itself, but fortunately the local Government body has had the wisdom to support the Bush Regeneration program and has been converted to the fact that, while it will take time, this tourist attraction will eventually return to its original state.

Case Study – Florida, USA

The Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council (EPPC) was established in 1984. The Council studies the impact of exotic pest plants on biodiversity, on the integrity of native plant community composition and function, on habitat loss and on endangered species. It manages a programme to inform and educate resource managers about which species deserve to be monitored and about setting priorities for management.

The EPPC listes exotic plant pests under two categories:

Category 1: Exotic plant pest which invade and disrupt Florida native plant communities, without regard to the economic severity or geographic extent of the problem.

Category 2: Exotic pest plants which have the potential to invade and disrupt native plant communities as indicated by:

- Aggressive weediness

- A tendency to disrupt natural successional processes

- A similar geographic origin and ecology to Category 1 species

- A tendency to form large vegetative colonies, and/or

- Sporadic, but persistant, occurrence in natural communities

|

| Much appreciated in its homeland, Melaleuca quinquenervia has proved to be a particularly unpleasant guest in south Florida. Photo: Brian Walters |

Australian plant species currently listed by the EPPC are:

Category 1

- Acacia auriculiformis

- Casuarina equisetifolia

- Casuarina glauca

- Cupaniopsis anacardioides

- Ficus microcarpa

- Melaleuca quinquenervia

- Melia azedarach

- Scaevola taccada var.sericea

- Schefflera actinophylla

Category 2

- Casuarina cunninghamiana

- Eucalyptus “camaldulensis” (identity uncertain)

- Ficus benjamina

- Hibiscus tiliaceus

- Murraya paniculata

Some of these listed species also occur naturally outside of Australia. The best known species for its invasive tendency is Melaleuca quinquenervia. This was introduced into Florida in the early 1900s and was soon widely planted as an ornamental and landscaping tree. It was also used as a means of drying up parts of the Everglades to decrease mosquitoes and allow development.

Since that time the tree has spread into almost every native ecosystem and is estimated to cover between 200,000 and 1 million hectares of south Florida. The plant is listed on the Federal Noxious Weed List and, as part of a campaign to educate the public about the problems posed by the tree, a brochure with the provocative title “Wanted: Dead not Alive” has been produced by the Florida EPPC.

The plant grows very densely and rapidly in the south Florida environment crowding out native vegetation and displacing cypress and sawgrass in the Everglades. The trees spread by both prolific seed production and adventitious root spread. Cut trees quickly resprout from trunks and roots.

The need to control the spread of the tree has been the subject of some debate over the years. The “Journal of Forestry”, July 1981 commented:

“If you are interested in causing a stir in south Florida, just mention that melaleuca is a very fine tree. You will rouse the ire of wildlife biologists, some doctors, some hydrologists and most naturalists. Or, using another approach, say that you regard melaleuca as the worst pestilance ever to find its way into the south Florida ecosystem, but be ready to take on local beekeepers, nurserymen who use it as an ornamental, and even some foresters who see it as an energy source for the future.”

Control of the plant is difficult but some progress is being achieved through the use of biological agents. In an article titled “It’s Aussie v Aussie in the battle for Florida’s wetlands”, the Sydney Morning Herald (8 July 2006) reports that the melaleuca snout weevil (released in 1997) and a psyllid (released in 2002) “have helped Florida to reclaim 40,000 hectares”. Physical removal, however, remains the principal means of preventing the spread of the species.

These notes were prepared (mainly) from material supplied by Amy Ferriter of the EPPC.

1. Case Study – Southern Victoria

The following article was published in the September 1990 issue of the Newsletter of the Victorian Region of SGAP. It describes the efforts of a group of dedicated environmentalists in tackling a weed infestation problem along the south coast of Victoria. Mary White, referred to in the article, died in 1996 at the age of 85.

Melaleuca hypericifolia (and other weeds)

Judy Barker

From June 11 to 17 it was Weed Week for Angair (Anglesea and Airey’s Inlet Society for the Protection of Flora and Fauna). During this strenuous week of fourteen sessions (morning and afternoon), volunteers remove “weeds” from the sensitive coastal and heathland environments. Mary White, president of Angair, not only supervises but takes vigorous part in this activity.

I went to four sessions and was surprised at how much was achieved as well as the extent and range of weeds present. At one session we removed Leptospermum laevigatum from a beautiful area of coastal heathland which was vibrant with the pinks of Epacris impressa, the yellow cones of Banksia marginata and the greenish-white propellers of Spyridium vexilliferum. At Point Roadknight we sawed off and removed the slender trunks of Melaleuca lanceolata that had been snapped off by vandals and left hanging. This is now a pretty, well mossed area with many small herbs returning since Mary and others have almost eradicated the Myrtle-leaf Milkwort (Polygala myrtifolia) that threatened to dominate this part of the coastal strip.

Another session was devoted to the removal of garden weeds, such as gazanias and succulents, which had just been dumped in the nature reserve instead of taken to the tip. We also pulled out seedlings of Coprosma repens, ltalian buckthorn (Rhamnus alaternus), and Senecio elegans from behind the dunes.

“Insidious Beast”

Around the camping ground at Anglesea we had an energetic go at boneseed, coprosma and scattered plants of smilax asparagus (Myrsiphyllum asparagoides) until we were overcome by expanses of this last insidious beast just scrambling over everything. Mary surveyed it grimly and said ‘We’ll leave that to the authorities’.

|

| Melaleuca hypericifolia is a good example of how even an apparently benign plant can become a pest under suitable conditions. The species is widely cultivated in many areas without problems. Photo: Brian Walters |

One session made an indelible impression on me. Five of us tackled an area within the grounds of the Scout Camp which had been planted with ornamental Australian natives some time before the Ash Wednesday (1983) bushfires. We set to work to remove seedlings 30 to 60cm high of Melaleuca hypericifolia and M.armillaris. We kept our heads down because if we looked up the hopelessness and immensity of the task almost overcame us. Fortunately, the preliminary attack was merely a lesson. Mary soon took us to the margin of this area, to a part where we could make some obvious improvement.

This is one of my favourite habitats – heath-woodland, where sweet little plants like hibbertias, heaths, leucopogons, goodenias and dillwynias carpet grey, sandy soil under stringybarks. It is open, generous, friendly bush.

After the fires, the area around the planted shrubs had been taken over by millions of their seedlings. Now there was an area larger than a suburban block entirely covered by the stout stems of Hakea laurina, H.drupacea (syn. H.suaveolens), Melaleuca armillaris and M.hypericifolia, ranging in height from 0.3m to 3m and quite impenetrable. Apparently this will be tackled by machinery at some future time.

Home groan…

Next day my husband and I spent an unscheduled session on our own block where I had been ill-advised enough to place two innocent plants of M.hypericifolia before the fires. It took us three hours to root out the two huge originals and the seedlings from our block and the block next door. And a large M.armillaris seedling — I had not planted that! Next time we go to our property we have an even longer job ahead of us: the removal of Kunzea ambigua. The horde of little (and big) kunzeas resulted from only two original plants.

In such sensitive environments it is a pity that the general public is not warned of the problem by local nurseries.

Thirty-four volunteers took part in Weed Week and logged one hundred and fifty-six hours. They have done a most valuable job.

2. Case Study – Southern Victoria

The following article was published in the March 1989 issue of the Newsletter of the Victorian Region of SGAP.

Jumping the Fence – Two Garden Escapees

Kathie Strickland

|

| The Western Australian bluebell, Billardiera heterophylla, is a popular light climber but has proven to be weedy in certain areas, particularly southern Victoria. Photo: Brian Walters |

Weeds are opportunist species which can take advantage of open ground and colonise areas rapidly. They can achieve this by efficient survival techniques such as:

- Production of numerous seeds

- Rapid growth

- Ability to withstand extreme conditions such as lack of shelter from wind and/or sun.

Many of our prized garden specimens can become weeds once established amongst native bush species. Even native species can become weeds when growing in a different habitat. Any change to the environment can alter a plant’s habits. One example of this is the proliferation of “Sweet Pittosporum”, Pittosporum undulatum, following the introduction of the European blackbird. This bird eats the Pittosporum fruits and distributes the seeds over a wide area.

Another pest is the Western Australian bluebell Billardiera heterophylla (formerly Sollya heterophylla). This species also produces copious seeds which are thought to be eaten by the blackbird and the Indian Myna, and again distributed far and wide. A result of this, to give one example, is the proliferation of the species,at “Seawinds” on the Mornington Peninsula, southern Victoria. This climber grows rapidly in the native vegetation, entwining through other species present. It could possibly pose as great as a threat as Boneseed, Chrysanthemoides monilifera, a problem with which many people may be more familiar (see the “Exotic Weeds in Australia” tab).

The WA bluebell is a favourite of many gardeners, with its dainty blue flowers and it is often sold in nurseries. It is a popular garden plant, often grown in total ignorance of its ability to colonise native vegetation to the detriment of the local bush.

Both of the native plants quoted here produce copious seeds which enable them to spread rapidly. Maybe we should become more aware of the characteristics of weeds and become more wary of planting such species in areas which are close to native bush.

Note: In South Australia, Billardiera heterophylla is now a declared weed species that must be controlled – it is banned from sale in that State.

3. Case Study – Western Australia

The following list was compiled by Greg Keighery for his “Annotated list of the naturalised vascular plants of Western Australia” (see the ‘Further Information’ tab) and was contributed by Rod Randall of the Weed Science Group, Agriculture Western Australia.

Extending their Boundaries

Western Australian plants causing problems in………Western Australia

The following are all Western Australian native plants which have become weedy somewhere in Western Australia. Many are popular in cultivation and this reinforces the need for care in plant selection.

Acacia blakelyi, Acacia lasiocalyx, Acacia microbotrya, Agonis flexuosa, Calothamnus quadrifidus, Calothamnus validus, Ceratopteris thalictroides, Chamelaucium uncinatum, Eucalyptus conferruminata, Hakea costata, Hakea francisiana, Hakea pycnoneura, Melaleuca lanceolata, Melaleuca pentagona, Nymphaea gigantea, Ottelia ovalifolia var.chysopetala, Solanum hoplopetalum, Solanum hystrix, Vallisneria gigantea, Verticordia monodelpha

Case Study – Boneseed and Bitou Bush

The following article was published in the December 1990 issue of “Eucryphia”, the Newsletter of the Tasmanian Region of SGAP (now the Australian Plants Society – Tasmania).

Flower of the Month – Boneseed!

Glenys Jones

Far from advocating the cultivation of this flower of the month, I would like to draw your attention to it, help you to identify it and encourage you to destroy this insidious and invasive weed of natural bushland.

Identification

Boneseed is a soft-wooded shrub up to about 3 m with oval fleshy leaves often with toothed margins. It is easily recognised by its bright yellow daisy flowers. It belongs to the daisy family (Asteraceae) and its scientific name is Chrysanthemoides monilifera. The genus name means “resembling a Chrysanthemum”; the species name means “in the form of a necklace”, which may refer to the seeds. Boneseed fruit are green at first, later turning brown to black. Boneseed has no spines or poisons.

|

| The attractive daisy flowers of Boneseed may distract attention from the invasive properties of the plant in suitable areas Photo: Brian Walters |

Distribution

Two sub-species have naturalised in Australia, Chrysanthemoides monilifera ssp rotundata (Bitou bush) and ssp monilifera (Boneseed). Bitou bush occurs along coastal areas of southern Queensland, New South Wales and Lord Howe Island. Boneseed occurs in Sydney, southern NSW coast, Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia and in limited occurrences in Western Australia. In Tasmania, infestations occur along the north-west coast and along the Tamar and Derwent Rivers including the suburbs of Taroona and Sandy Bay, Rokeby, and Margate.

The species invades both disturbed and natural areas including coastal heaths, open eucalypt forest, and littoral rainforest communities. It is, however, advantaged by disturbance so that areas of soil erosion and fire-cleared areas are particularly prone to colonisation.

History

Like many of the weeds and pests in Australia, boneseed bush has an interesting history. It was recorded as a garden plant in both Melbourne and Sydney in the mid 1800’s. Around 1950, the ability of boneseed to colonize and stabilize disturbed areas was recognised and the species was actively put to use by soil conservation agencies to stabilize coastal sand dunes after mining for mineral sands. However, the success of the species as an invader was underestimated and it has now become established along hundreds of kilometres of coastline along eastern Australia, becoming the dominant species over much of its distribution.

|

| Boneseed has developed a monoculture and displaced native Banksia woodland on these dunes on the NSW central coast. The pink flowers are yet another exotic weed Photo: Brian Walters |

It is one of the few significant weed species of non-agricultural land. It is therefore not a significant economic problem and so tends not to be recognised by State governments as a noxious weed. Boneseed was proclaimed a noxious weed in Victoria because of the direct threat it posed to the structure and composition of native bushland and the indirect threat to birds and animals by the alteration of their habitat.

Method of Spread and Control

Boneseed does not normally spread vegetatively. It is all by seed. It is the sheer fecundity of the species or its ability to reproduce huge numbers of seeds that causes all the problems. One mature plant can produce up to 50,000 seeds in one season. And seeds may lie dormant for up to 15 years. The seeds are relatively large and heavy and so tend to drop around the adult plant. But the fleshy drupe is edible and seeds can be dispersed by animals and birds.

Individual plants are relatively easy to kill – by fire, herbicides (Roundup or Zero can be used as a foliage spray at dilution of 1:100 or as a paint on cut stumps at a dilution rate of 1:15) or by physically chopping or hand-pulling them out. Hand-pulling is probably the best method of eradication wherever possible as it offers the advantages of minimising disturbance to non-target species which is particularly important in bushland communities. Re-growth does not occur from roots left in the ground and seedlings are easily pulled by hand.

Books and Articles

- Auld, B.A. and Medd, R.W. (1992, Revised Edition); Weeds: An Illustrated Botanical Guide to the Weeds of Australia, Inkarta Press, Melbourne and Sydney.

- Bradley, J (1988); Bringing Back the Bush, Lansdowne Press.

- Buchanan, R (1989); Bush Regeneration; Recovering Australian Landscapes, TAFE Student Learning, Publications, Sydney

- Department of the Environment Sport and Territories (1996), Australia: State of the Environment 1996, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Australia.

- Felfoldi, E (1993); Identifying the Weeds Around You, Inkarta Press, Melbourne and Sydney.

- Hussey, B.M.J., Keighery, G.J., Cousens, R.D., Dodd, J. and Lloyd. S.G. (1997). Western Weeds, a guide to the weeds of Western Australia, Plant Protection Society of Western Australia, Inc.

- Julien, M, McFadyen, R, and Cullen, J. Biological Control of Weeds in Australia, CSIRO, March 2012 (available in hardback and ebook).

- Keighery G.J. (1995). An Annotated List of the Naturalised Vascular Plants of Western Australia, Appendix 2: “Invasive Weeds & Regenerating Ecosystems in Western Australia” Proceedings of the conference held at Murdoch University, July 1994. Burke G. (Ed), Publisher, Murdoch University

- Lamp, C and Collet, F (1989, 3rd Edition); Weeds in Australia, Inkarta Press, Melbourne.

Internet

- Australian Association of Bush Regeneratorshttps://www.aabr.org.au/ – Weed lists and information on ‘bush-friendly’ garden plants.

- Guests and Pests – Australian Plants overseas. Some problems with Australian species in other countries.

- Bitou Bush and Boneseed – chapter from the book ‘Biological Control of Weeds in Australia’ (see above).

- Environmental Weeds in Australia – List and photographs of serious pest species.

- Prickly Pear History – The story behind the introduction, spread and control of prickly pear in eastern Australia.

- The introduced flora of Australia and its weed status – Comprehensive database of weed species – publication available for download.

- Three (More) Rogue Aussies! – Australian plants causing problems in Florida, USA.

- Weed Risk Assessment System – Assessing the risk of plant introductions – includes an Excel 5 spreadsheet for assessing the potential “weediness” of species.

- Weeds Australia – An Australian Weeds Committee National Initiative detailing current issues, lists of weeds of national significance, weed management, noxious weeds lists.

- Weeds of Blue Mountains Bushland

- Weeds – The Silent Invaders. A look at some of the worst environmental weeds in Australia.

- When Native Plants Go Feral. They may be natives but does that mean we have to love them?

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)