Garden Design Study Group: Marriott Garden

Stawell area, central Victoria

Background Data

Area |

80 hectares total; 8 to 10 hectares closely gardened. |

Orientation |

Hilltop with aspects in all directions. |

Climate |

Semi-arid, with extreme weather events. |

Soil Types |

Mainly low pH acid granitic sands and sandy loams. |

Mulch |

Inorganic. |

Water Supply |

Tanks and mains water. |

Planning Zone |

Property is in Rural Conservation zone, Northern Grampians Shire. |

Photographs |

Neil and Wendy Marriott; Diana and Brian Snape; one other, labelled. |

Click on the smaller images to view larger images.

Property and Area

The property, Panrock Ridge, is an eastern ridge of the Black Range situated east of the Grampians and south of Stawell in central Victoria. It has a Trust for Nature covenant. Its total area of 80 hectares has a rabbit-proof fence and, within this, between 12 and 16 hectares has a modified covenant allowing some limited development. A feral-proof fence encloses this inner area, maintained to prevent the entry of all feral animals. Within this area again, 8 to 10 hectares is more closely gardened.

Orientation

From the crown of the hill, the property has aspects in all four directions. Many microclimates are created by the exposed granite tors and the garden is oriented to take advantage of the variation this provides. For example, verticordias are grown exposed to prevailing winds to prevent fungal problems when it is colder in winter. The slope to the northeast is steepest, with a gradient of about 1 in 6. The warmer slope to the north enables sub-tropical plants to be grown, with rainforest plants lower on the slope.

Climate

Over the years, Neil has noticed a marked change, from a Mediterranean climate to a semi-arid one. Since 1996, the rainfall has dropped from between 650 and 700 mm per year, to between 300 and 400 mm per year. The climate has also become more highly erratic. There can be occasional heavy summer storms, with a single storm yielding 130 mm of rain. Autumn is usually hot and dry and winter can be cold and drizzly, but spring is virtually non-existent.

Soil types

Near the top of the hill, the soil consists of very shallow granitic sand overlying clay loam or granite slabs. Towards the valley, the sand gets deeper and in the valley, it is metres deep. Granitic sand was quarried half way down the hill for use in building up garden beds. The soil drains well but also dries out quickly. Soil for the trial scaevola bed (see later) and gravel mulch were the only soil materials brought in from outside the block.

In most areas, Neil and Wendy found that soils were hyper-acidic and brought up toxic minerals containing manganese. Soil samples tested had an average ph of 4.3. To neutralise these soils, organic mulch was removed. Lime (at a tonne to the hectare) and dolomite (at half a tonne to the hectare) were applied and deeply ripped in.

Water supply

|

|

|

| Left: Erecting the windmill Right: The lake |

||

There are five tanks altogether, of which one of 26,500 litres and another 22,700 litres are used for the nursery. For the nursery and the area of cut-flower production, there is a reticulated system using drippers and a time clock. For the rest of the garden, it’s a matter of hand watering from the mains system.

Before the fire on New Year’s Eve 2005/6, a windmill pumped water up from spring water collected in a lake at the bottom of the valley. The extensive reticulated watering system, which included the grevillea garden, was completely burnt in the fire. It was not replaced as, during the drought preceding the fire, all the springs had dried up. Rainwater goes straight into the soil and there is no run-off to collect.

Mulch

Since the fire, only inorganic mulch such as gravel is used, especially anywhere near the house. Organic mulch is a serious fire hazard and also tends to acidify soils as it decays.

The Development of the Garden

|

|

|

| Left: The land before the garden was started, looking east over the yet to be developed Grevillea Garden Right: The revegetated drive between stands of Eucalyptus aromaphloia |

||

Initially the land was a typical grazing block, with cropped grass and bare rocks. There were some big, old scattered Eucalyptus aromaphloia (Scent-bark), E. melliodora (Yellow Box) and Acacia implexa (Lightwood). Down in the valley conditions were swampy and wet, with E. camaldulensis (River Red Gum) growing there. Rabbit warrens and exotic weeds were a widespread problem, with one hillside covered with St Johns Wort.

There were numerous major stages (more than ten) in the development of the Marriott garden. The very first planting was along the drive, of trees and shrubs indigenous to the area. This was carried out in 1993 by staff from Whitegums Nursery, owned by Neil and his former wife Jane. All the plants used were propagated at the nursery. The second planting in 1994 was of the cut close to and NNE of the house, visible from inside the house.

In the third stage, a grevillea garden was planted south of the house in 1994. This garden was burnt on New Year’s Eve 2005/2006. Following the fire, 15% of the grevilleas regenerated from seed, 15% from lignotubers or epicormic growth, while a few hybrids also appeared. For one example, hundreds of Grevillea manglesii hybrids regenerated from seed.

Stage 5 included the planting of a second grevillea garden in 1995 on the NE facing slope but, sadly, after the 2006 fire there was only limited regeneration in this area.

Also in 1995 a garden was planted close to and south of the house. Now a key feature of this area, several fine examples of Eucalyptus caesia grew from gumnuts on branches originally used as mulch. Next, a big eremophila mound was planted on built-up clay not far from the house, as a screen for fruit trees. Some of these eremophilas are now huge shrubs.

|

|

| Top: Regeneration of Dizygotheca elegantissima/ Polyscias fruticosa Bottom: Waratahs (Telopea speciosissima) |

A rainforest was established near the bottom of the NE slope, watered by natural springs at the top of the garden, as water seeped downhill through the subsoil. 1997 was the start of the drought and the springs have never flowed again. Though, in contrast to their reputation, some rainforest trees came back after the fire, lack of water due to climate change has hindered their regrowth. Well down the slope, a number of tropical grevillea including several Grevillea banksii, G. helmsiae and G. venusta are all 3 – 5 metres high and thriving.

The following stage was carried out in 1997 (as it turned out, the start of the drought), further down the valley in deep sand. 40 waratahs and 250 Banksia coccinea plants were put in and were thriving. Neil and his sister-in-law were selling hundreds of cut flowers per week. As they have lignotubers, all the waratahs survived the fire. Only six banksias survived the fire and there was a massive seed release, but no natural recruitment followed.

By 1998, the nursery had been built and luckily it could be saved from the fire by its installed watering system. In 2004, terraced gardens to the north-east of the house were built and planted with banksias and dryandras. These were mulched with sand rather than organic mulch and survived the fire. However, with sad irony, dryandras in shallow soils were mostly all lost when flooded in 2011.

After the terrible destruction of so much of the garden by fire at the end of 2005, Neil and Wendy were devastated and worked in Dunkeld for about a year. They recorded regeneration that was occurring despite ongoing dry seasons, however in 2008 they created a verticordia garden south of the house (about stage 10!). This garden is planted with drought-tolerance in mind. It is viewed from the house and was designed to enhance the Grampians view. (In the late nineties this area was the site of a garden where Rodger Elliot had a trial plot of scaevolas and, for a while, it was a pumpkin patch.)

Next, a small garden was created around large rocks near the verticordia garden and fill-in planting was carried out around the old grevillea garden to the south. In 2009, a baby banksia garden was planted below the nursery.

2011 saw a major undertaking, when a vermin-proof fence was installed around an area of 12 – 16 hectares. Dramatic differences are visible inside and outside the protection offered by the vermin-proof fence, which excludes foxes and cats in addition to rabbits. (It also keeps out kangaroos and wallabies.) The cost of materials for the fence was $12,000 but there was no cost for the construction, carried out by ‘Landmate’, using volunteer labour from the local Ararat prison. Also a good friend built a potting shed for use at the nursery.

In 2012, Wendy began creating an acacia walk beside a track through the indigenous area further north from the house. This has been supplemented annually and now has about 200 species of wattle with some multiples, and also different forms. Two years later, between the Acacias and the fence, Neil planted a hakea walk with about 120 different species, mostly with three plants of each.

Most recently, the area of cut flower production has been set up with a dripper system and replanted. The banksia garden has been replanted over the last three years, the collection now having about 60 species, including Banksia rosserae (in flower when we visited).

Banksia rosserae

Of course much other work has been carried out within the 8 – 10 hectares. There is the extensive nursery, vegetable garden and fruit trees. The scope and scale of the total garden area is extremely impressive.

Aims and Motivations

|

|

| Top: Thryptomene denticulata Bottom: Dryandra sessilis (syn. Banksia sessilis) |

The first specific aim was to establish a comprehensive collection of grevilleas. The garden still has the National Plants Collection Association grevillea collection. Neil is an extremely active member of the Grevillea Study Group of the Australian Native Plants Society (Australia) and co-author of the 3-volume The Grevillea Book. He has been involved in finding around 50 new species and very many new forms of grevillea, especially in Western Australia.

The second was to establish a naturalistic Australian garden, incorporating as broad a range of species and forms as possible. Examples include many forms of Banksia spinulosa, 40 forms of Grevillea alpina and several forms of Thryptomene denticulata (which Neil says are brilliant in flower from February to September, and are mass planted in the north courtyard gardens).

A third aim is to establish collections of eremophilas, banksias and dryandras, in addition to the grevilleas.

However the fundamental, overall objective and motivation is the conservation of indigenous species – plants and also the wildlife dependent on these plants, including mammals, birds, reptiles and invertebrates. In Neil’s words:Today, as the gardens again begin to mature, our aim is to create a harmonious display of some of the real gems of the Australian flora, in a way which highlights the plants against contrasting foliage colour and texture, while providing habitat for our huge diversity of birds. Few attempts are made to mix and match flower colours, as it is the foliage variations that make a garden look good together for the whole year. Likewise, we are always looking for ways to incorporate our local shrubs, lomandras and grasses into the designs, so they look attractive and natural, while supporting our local fauna.

These aims collectively have been the focus of the design of this garden.

Neil and Wendy, in their work and in their lives, are deeply committed to and passionate about conservation of the natural environment. Neil worked for 18 years for Trust for Nature and is the author of ‘The Right Plant for the Right Place – a Revegetation Guide for the Wimmera’ (1995, Department of Natural Resources and Environment); ‘Grassland Plants of SE Australia – a Fieldguide’ (1998 Bloomings Books), as well as ‘The Grevillea Book’ Volumes 1-3 (1994 Kangaroo Press).

Wendy was mentored in conservation with the Melbourne indigenous nursery group Greenlink Box Hill, after studying horticulture and natural resource management at NMIT. She then worked as a bush regenerator with Save the Bush and in various roles with Greening Australia, who were happy to transfer Wendy to Hamilton in Monitoring and Evaluation, and later in the Green Corps partnership. Now married, Wendy and Neil work together in their environmental consultancy and nursery and are active on many committees and projects particularly landcare, grassland ID, native plants and education. They are also extremely active with WAMA (The Wildlife Art Museum of Australia), as Neil is the Site Development Team Leader working with the aim of developing a superb native botanical gardens on the WAMA property at Halls Gap on the edge of the Grampians in western Victoria. They also lead annual spring botanical trips to Western Australia with Birdswing Wildlife Tours.

Feelings About the Garden

Initially, Neil was concerned when plants in some areas struggled. However, once the hyper-acid soil was identified and successfully treated, the success of the garden was fabulous. For the first 12 years, it gave them great joy as almost all the plants flourished and they began to achieve their aims. They were also pleased to be able to grow a large number of endangered plants, for example at one stage they had more plants of Grevillea scapigera growing in their garden than grew in the wild. They still have more plants of Grevillea phanerophlebia in their garden than occur in the wild!

With the onset of the drought and the effects of climate change, it has become more difficult and less satisfying for them. They have lost their natural water source. Neil and Wendy have been twice threatened by fire and had the stress and worry of fighting it themselves. The gardens were burnt out once, with tremendous loss of plants. Each summer now they are very conscious of the fire risk.

Painted Button-quail

Photo: John Barkla

However, they have been helped and encouraged – and delighted – since 2011 by the marvellous increase in biodiversity inside the feral-proof fence. With no foxes and cats, it is very exciting to see the spectacular birdlife around the house. Superb Blue Wrens, Red-browed Firetail Finches, Diamond Firetail Finches and the rarely observed Painted Button-quails are nesting close to the house and, with Peaceful Doves and New Holland Honeyeaters, can be seen daily from the dining table. Goannas, small lizards and Yellow-footed Antechinus are also now numerous in the garden as are many butterflies, native bees, wasps and moths. The absence of kangaroos and wallabies inside the fence allows regeneration of indigenous trees, grasses and other flora. (Kangaroos and wallabies still have the remaining 64 hectares of the property to feed in.)

They also still delight in the healthy growth and flowering of so many special plants, although aware of the fragility of their existence despite all the care taken. Just seeing a single rare plant in flower can give great joy.

|

|

|

| Left: The rare Paphia meiniana Right: Pimelea physodes |

||

Design Challenges

There are three really major design challenges. The first and over-riding one is climate change. Not only has this affected the climate and rainfall throughout the year but it has caused the loss of the springs that were so important in watering large areas of the garden. In addition, big, established trees have dropped dead where their soil, lying over big slabs or floaters of granite, is now too shallow to retain enough water when once it could be sufficient. Garden beds have had to be relocated for the same reason.

The garden now has to be designed with the possibility of fire in mind. It is a bad idea to grow eucalypts close to the house (the E. caesia are within the house fire sprinklers). On the other hand, all ferny-leafed wattles survive fire and, Neil says, Acacia mearnsii (Black Wattle) is priceless as a medium sized, fire-resistant tree. A. pycnantha (Golden Wattle) and A. implexa (Lightwood) are also fire-resistant. It is essential that inorganic mulch such as gravel be used around the house.

|

|

|

| Left: Hillside of acacias and burnt eucalypts shows fire resistance of wattles such as Acacia mearnsii and A. implexa Right: Acacia pycnantha with Banksia spinulosa ‘Schnapper Point’ |

||

The hyper-acid soils in some areas were an initial problem but the treatment with lime and dolomite already described has cured this problem, wherever they have been applied.

Another design problem would have to be the sheer size of the property, the scale of the planting projects, and the variety of micro-climates and micro-niches available. This makes it a complex challenge to carry out planting, trying to match both garden areas or beds, and individual plants, with suitable situations.

One constraint on design is that no regenerating bushland has ever been cleared. The compensating benefit of this is that the garden is framed by its bushland setting.

Large areas of native grasses are seen as a bonus, not a problem, and are used, where possible to show off, and contrast with, the non-indigenous plants grown in the adjoining gardens. These grasses are mown close to the gardens and for access, with large areas left till the end of spring for wildlife to nest in and the grasses to drop their copious seed for the native birds. Come early summer big areas are mown down for fire safety, although natural areas are still retained for wildlife.

Austrostipa mollis with Grevillea oligomera

Work in the Garden

The longest period Neil and Wendy are away from the garden during the year is one month, with three or four further separate weeks away. They not only have the garden and nursery to look after but also grow organic fruit and vegetables and have chooks and dogs. It is common for them to work all day in the garden. They occasionally have help from friends including members of the Grevillea Study Group, who provide great support by way of annual working bees and get-togethers.

To get plants established, they are watered weekly for the first summer, then are on their own. An exception is made if there is a very dry spell, when the sprinkler is put on once every 3 or 4 weeks, on a needs basis. When required, plants may be given a 2 or 3 hour soaking with mains water, while water from the tanks is used for the house and the nursery.

A lot of rejuvenation is carried out whenever possible – removing plants that have not succeeded or become scruffy, often because they are no longer climatically suitable. Neil and Wendy do not have enough time for all the pruning they would like to do, though they have some very helpful friends. Prunings are composted and loads of compost has been added to the soil. Another friend often does chipping for them. If plants are diseased they have to be piled up and burnt. Propagation is carried out throughout the year but nowadays, with climate change, planting is restricted to late autumn and winter. Some plants are grafted and grafter friends often return the favour of propagation material with a grafted plant for the garden. Otherwise they are expensive as this process is time-consuming, taking 5-10 minutes per plant.

Plants

Neil and Wendy grow a great variety of food plants – vegetables, herbs and a lot of fruit. (They also have a dozen free-range chooks, protected from foxes by the feral-proof fence, and get a dozen eggs every few days.) They are almost self-sufficient, and able to barter or give away produce.

Otherwise their whole garden consists of Australian plants and, for the larger part of the property, these are indigenous. (There’s one little exception – a small garden with roses and lavender put in by Katy Marriott as a child.) In the closely gardened area, there are a greater variety of species. The total number of species is well over 1,000, let alone the number of plants. To detail them all would require a small book.

They have about 80 species of eucalypt (Eucalyptus, Angophora and Corymbia species). A beautiful dwarf form of Corymbia ficifolia with orange flowers grows close to the house. On the warm and dry north side of the hill, the mallee garden has lovely plants of a large range of mallee eucalypts including Eucalyptus synandra, E. pendans, E macrocarpa, E orbifolia and E erythrocorys. Apart from the large number of species of shrubs in the collections of the genera already mentioned – about 300 grevilleas, 150 acacias, 200 hakeas, 60 banksias and 20 dryandras – there are about 30 species each of verticordia and members of the family Goodeniaceae, and various species of darwinias, chamelauciums, thryptomenes, lomandras, Grasstrees, daisies and others.

Many are rare plants, such as Banksia goodii, B rosserae, Grevillea scapigera, Grevillea lissopleura and Dryandra catoglypta and many are endangered. There are also numerous special forms of species – an orange form of Grevillea johnsonii, a white Hemiandra linearis and a red form of Hemiandra gardneri, the rare but beautiful creeping Dianella amoena, the deep orange Pileanthus aurantiacus, or the pinky-red Pileanthus rubronitidus, the dwarf form of Grevillea magnifica and Grevillea petrophiloides and many more.

|

|

|

| Left: Indigenous grasses – foreground, Austrostipa mollis (Soft Spear Grass), background Microlaena stipoides (Weeping Grass) Right: Backlit Rytidosperma bipartita (Wallaby Grass) |

||

With an area of 8-10 hectares to garden, plants can be accommodated in conditions from full sun through to full shade. They have tried a number of groundcover plants but have found that few are dense enough to suppress exotic grasses and other weeds, a legacy of the land’s history as a former grazing property. Many grevilleas are also not dense enough to suppress weeds and they have need of more moisture. A few groundcovers found to be successful are Kunzea pomifera (Muntries), Myoporum parvifolium, Hemiandra pungens, Thryptomene denticulata – prostrate form, Acacia cardiophylla ‘Gold Lace’, Eremophila biserrata and Grevillea leptobotrys.

Apart from restricted mown areas of grass, quite close to the house, there are several beautiful areas of indigenous grasses such as Themeda triandra (Kangaroo Grass), Microlaena stipoides (Weeping Grass), Austrostipa mollis (Soft Spear Grass) and Rytidosperma bipartita. (Wallaby Grass). Microlaena stipoides remains green under dry conditions while the others become green again when it rains.

Interested groups and Australian plant enthusiasts frequently visit the garden and any visitors who are happy to help out with a few chores in the garden are invited to visit. Wendy and Neil also have a B & B Cottage “Grampians Grevillea Cottage” on Airbnb which visitors are welcome to book, and usually includes a free tour of the gardens.

Neil showing some visitors the garden, Scholtzia uberiflora flowers

in foreground, house and cottage in background

|

|

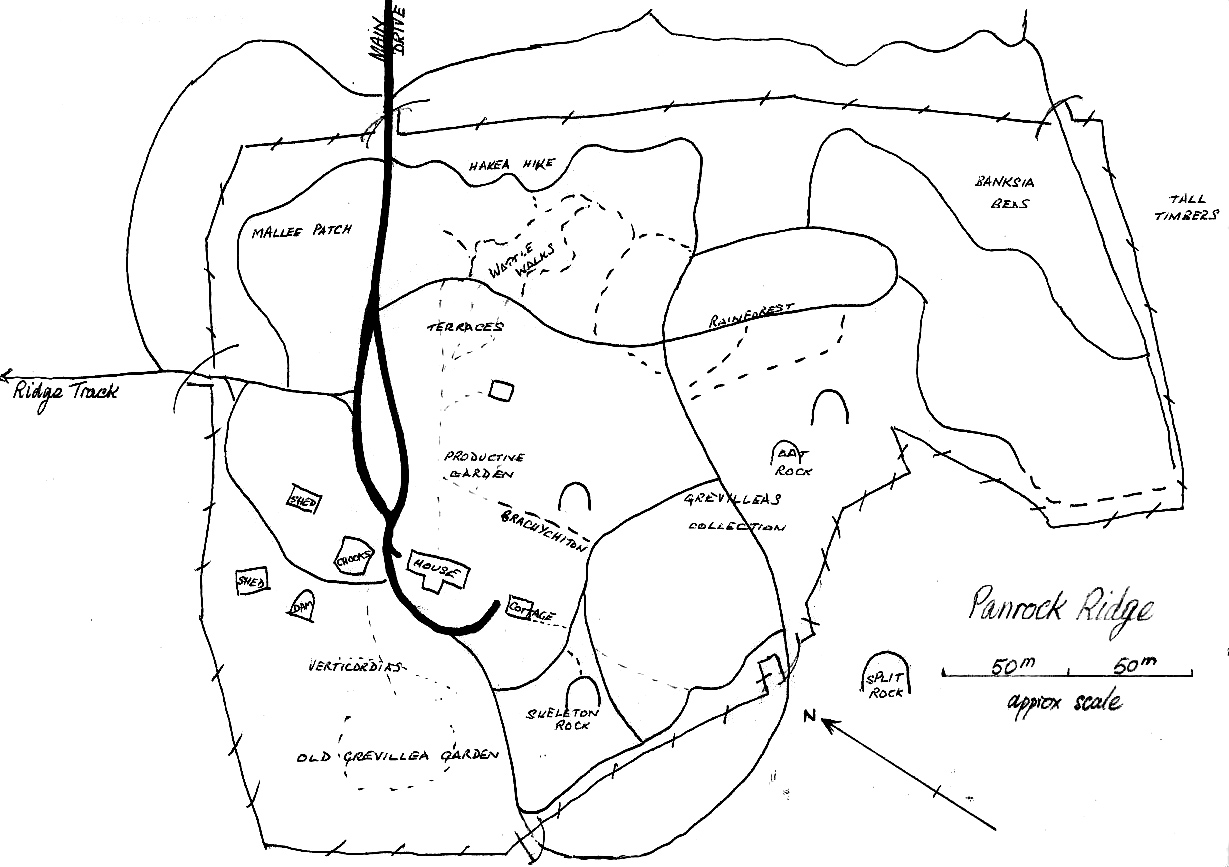

| Map of the predator-free area of the garden | |

| Scroll image horizontally if it exceeds the width of the display | |

Design of the Garden

Setting

|

|

|

| Left: View of house from the north, with Veronica perfoliata in foreground Right: View to Redman Bluff, with blue Lechenaultia biloba and pink Chamelaucium megalopetalum in flower |

||

The house has a south-westerly aspect and is sited just below the brow of the hill, to make it less prominent in the landscape and to minimise the effects of hot northerly winds. The south winds also tend to go over the house, which is placed to maximise views of the Grampians. The shared landscape is extensive and magnificent. From the house site, to the SW, the Black Range is close and the Mount William Range more distant. To the north, visible from the block, are the Pyrenees Ranges and to the east, Mt Langi Ghiran and Mount Cole.

Some aspects of design

When the site was levelled for the house, tonnes of soil were removed and used to create garden beds wherever wanted, for example 10 tonnes for the eremophila garden. Agricultural pipes were used to drain the area just north of the house, where plants were planted directly into a bank of solid, sticky clay. The clay provided good nutrients and, with adequate drainage, plants grew well. Key plants in this area include mass plantings for winter colour, of Banksia spinulosa ‘Schnapper Point’, a select form of Thryptomene denticulata, interspersed with Lomandra confertifolia ssp rubiginosa and Grass-trees (Xanthorrhoea sp). These are edged with a transparent screen of Acacia merinophthora, leptospermums and Eucalyptus synandra. In spring a local low, rounded form of A. pycnantha, and the superb double flowered form of Bendigo Wax Philotheca verrucosus set off a display of flowering tub plants.

There is a brick-paved area north of the house and a natural stone path to the front door. Gravel or sand paths lead through the verticordia garden. Otherwise paths are just mown, as it is too difficult to maintain gravel paths throughout such a large area. (Native grasses are allowed to seed for finches.) There are vistas throughout the garden, most with a beautiful background of trees, rocks and views of the natural landscape. The feral-proof fence, though high, is most inconspicuous, so the garden appears to have no limits.

Buildings other than the house are hidden by screening. The nursery is naturally visible only on the north side, from where it is completely hidden by planted banksias and grevilleas. The chook yard is screened by the early eremophila bank, which now has large, mature eremophilas, for example an E. santalina four metres high. Watertanks are inconspicuous among trees at the top of the hill.

The structure and design of the garden have evolved over the years with increasing experience. The first gardens were constructed close to the house, then other gardens gradually further away. Later, four terraces were levelled to accommodate the nursery.

In the early years, before the drought, a few ephemeral creeks were put in, lined with heavy duty plastic. Sadly these have never flowed. Several lovely pools were also created, now thick with reeds and rushes. A hose is used to regularly fill a number of water bowls for birds in the gardens close to the house. Additional seed is supplied for the fairy-wrens, finches and button-quails that now frequent and nest in the garden.

Ephemeral creek bed with grey-foliaged plants including a selection

of Dianella revoluta on the left and Dryandra drummondii

(syn. Banksia drummondii) on the right

Of course each of the specific garden areas has involved design. There are a number of productive areas – nursery, orchard, vegetable garden, area of cut-flower production. The design of these is beyond the scope of this record.

Visiting the garden

You enter the garden by a curving drive through an indigenous landscape that looks entirely natural but was created initially by the owners’ planting. Since then it has matured, with some losses over the years and much natural regeneration. As you pass through the feral-proof fence, you notice the difference in density of vegetation. Two local shrubs that have regenerated where grazing has been prevented are Leptospermum myrsinoides (Silky Tea-tree) and Calytrix tetragona. Amongst the rock outcrops superb large Sweet Bursaria trees (Bursaria spinosa) are colonising, along with the local form of Grevillea aquifolium. Other species include Hedge Wattle (Acacia paradoxa) and Cherry Ballart (Exocarpus cupressiformis).

Entrance garden features Eucalyptus macrocarpa with, from left,

Austrostipa mollis, prostrate Grevillea pinaster and Eremophila glabra

Just inside the entrance gates, small gardens on either side provide focal points. The created garden as a whole blends seamlessly with the natural landscape, which both frames and penetrates it. Granite rock formations and indigenous trees are the most conspicuous linking features, while in some areas swathes of Australian grasses soften the ground. With climate change most of the local Scentbark (Eucalyptus aromaphloia) have died out, and been replaced by groves of Drooping Sheoke (Allocasuarina verticillata) and Lightwood (Acacia implexa). The Lightwoods have been trunked up to promote their superb dark, deeply furrowed bark, and are now a feature of the ridge.

Left: Back courtyard garden with standard grafted Grevillea tenuiloba in pot, Grevillea ‘Wendy’s Sunshine’, Darwinia macrostegia and blue Lechenaultia biloba

Centre: Cottage garden west of door on southern side of house with, from left, Maireana sedifolia (Bluebush), purple Dampiera rosmarinifolia and pale pink Hypocalymma angustifolium

Right: Cottage garden east of door on southern side of house with, from left, white-flowered Grevillea anethifolia and pink/purple Thryptomene stenophylla

Once inside the feral-proof fence, you could choose any one of a hundred appealing routes through the garden, depending on your mood or particular interests. The only set paths are those close to the house or to work areas such as the nursery and orchard. Looking around the house first, on the northern side, the steep banks provide a planted backdrop for an intimate area outside the kitchen and dining room. The gardens on the southern side are especially attractive in spring with their beautiful colour schemes.

|

|

|

||

| Left: Verticordia grandis; Center: Verticordia oculata; Right: Verticordia ovalifolia | ||||

The verticordia garden to the south of the house, in the foreground of the view, has a wonderful selection of small and medium shrubs giving year round interest. The massing of these is attractive. Individual plants can be admired from two curved paths that wind through the garden. There are many special species here, for example Verticordia grandis, Verticordia ‘Wemm’s Find’, V. ovalifolia, V. meulleriana and V. staminosa.

In addition to a multitude of plants, there are birds and other native animals to enjoy as part of the created ecosystem. The placement of plants in separate garden areas has been guided by design, in addition to practical considerations of soil, orientation and shelter. Some gardens are largely collections of a particular genus but, even so, both siting and arrangement of plants (usually shrubs) are sensitive. Other genera have been included to increase variety, or provide a contrast.

The magnificent grevillea garden destroyed by the 2005/6 fire is very different now with many beautiful grevilleas surviving and replanted. Other iconic Australian genera such as waratahs, banksias and dryandras still feature, largely in their own areas. One special banksia is the rare B. rosseri, discovered and described in a paper by Neil and Peter Olde in 2002. They named this banksia after the ‘banksia lady’, Celia Rosser. Other examples of plants Neil has discovered and can be found growing are Callistemon wimmerensis, Grevillea marriottii, discovered by Neil in 1987, Grevillea ferox ms, Grevillea chiddarcooping ms, and Grevillea nana subsp nova ‘Chiddarcooping’.

Apart from the major planting collections and gardens, smaller gardens exist with new and interesting combinations of plants. One very appealing aspect of the whole garden is the integration of existing large boulders by informal planting around or adjacent to their bases. The granite rocks themselves are full of character and their interest and beauty have been highlighted by the complementary planting.

Because of the topography of the site, plus the existing rock formations and indigenous vegetation, the layout of the garden is complex. Its sheer extent, the number of different areas and beds, and the number and variety of plants, make it difficult to absorb the garden as a whole. From any one point, only a relatively small section is visible. It is like an extensive botanic garden situated in a park. There is always space, so no garden is crowded. Each area is different. As you move from one area to another, wherever you go, there are both large- and small-scale delights.

The garden is interlinked and imbued by the enthusiasm, knowledge, sensitivity and skill of the owners who have created it. After the tragedy of the fire that destroyed so much of the garden, they have had the courage to start again. With consistent hard work, they are once again successfully achieving the goals that have been the inspiration for this outstanding garden.

Diana Snape

28 November 2017

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)