Waratah & Relatives – Background

Introduction

The Protea family (Proteaceae) is spread across what was once Gondwana, through Southern Africa, Australia and South America. A great many of them, including many of the more spectacular species (many banksias, grevilleas and proteas), come from Mediterranean or arid areas of low summer rainfall – wetter climes provide considerable (and in some cases insurmountable) challenges to their cultivation – ask any enthusiast living in Sydney or Brisbane!

The Tribe Embothrieae is a collection of plants from quite different climates to their abovementioned kin, the bulk of which grow instead in the rainforests and wet highlands of coastal eastern Australia – from tropical Queensland to southwest Tasmania, as well as in New Guinea, New Caledonia and forests in Peru, Ecuador and Chile. There are some exceptions – the New South Wales’ Waratah grows in dry sclerophyll forests and the 3 species of the genus Strangea grow on sandy heaths and sclerophyll forest. Also, two species of Stenocarpus grow in dry areas of the Northern Territory and north west Western Australia but are inundated in the monsoon season there.

One genus, Lomatia, has representatives on both sides of the Pacific. Until recently, so did Oreocallis, however, the four species in Australasia were considered distinct enough to be placed in the closely related genus Alloxylon. Furthermore, fossil records seem to indicate the presence of Embothrium (now comprising a single species, E.coccineum or Chilean Fire Bush, native to southern Argentina and Chile) in Gippsland in Victoria. Given their current distribution and Antarctica’s position between South America and Australia in Gondwanaland prior to its breakup in the late Mesozoic, one could assume waratah-like plants occurred in Antarctica (!).

Botanically the Tribe Embothrieae contains four subtribes. The table below lists the 9 genera in the Tribe and indicates the approximate number of species in each.

Genera in the Tribe Embothrieae*

|

Genus

|

No.of Species*

|

Distribution

|

|---|---|---|

| Subtribe Embothriinae | ||

|

Telopea

|

|

Eastern Australia

|

|

Embothrium

|

|

South America (Chile)

|

|

Oreocallis

|

|

South America (Ecuador and Peru)

|

|

Alloxylon

|

|

Eastern Australia, New Guinea

|

| Subtribe Lomatiinae | ||

|

Lomatia

|

|

Australia, South America

|

| Subtribe Buckinghamiinae | ||

|

Buckinghamia

|

|

North-eastern Australia

|

|

Opisthiolepis

|

|

North-eastern Australia

|

| Subtribe Stenocarpiinae | ||

|

Stenocarpus

|

|

Northern and eastern Australia

|

|

Strangea

|

|

Eastern and south Western Australia

|

| * Approximate number only; some genera contain unnamed species and other genera are in need of botanical revision. | ||

Characteristics

Generally the Embothrieae comprises plants of rainforests, open forests and mountainous areas. Within Australia, the group is generally limited to the eastern seaboard but certain genera (eg. Stenocarpus) extend across tropical Australia to northern Western Australia.

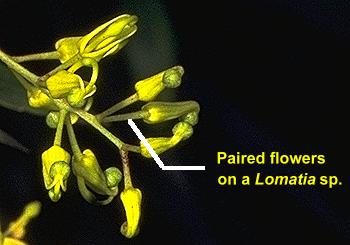

In many cases, the flowers are showy and and occur in clusters at the ends of the branches (“terminal” inflorescences). The individual flowers are small and occur in pairs, a characteristic shared by many other members of the Proteaceae, including the well known genus Grevillea – the Embothrieae, in fact, belong to the large sub-family Grevilleoideae, which includes Grevillea.

For the most part the flowers have little or no fragrance and many are red in colour, which suggests that birds rather than insects are the main pollinators being catered for. Blooms are generally followed by woody seed pods containing from a single (eg Strangea) to many seeds (eg. Telopea). The seeds are released from the seed pods when the pod is mature, some months after flowering is finished, Seeds generally have a membranous wing attached which aids in distribution of the seeds by wind.

Many species can grow into large trees up to 30 metres in height in their natural forest habitat, though often much shorter in the garden. The genera which in general stay at shrub size are Telopea, Strangea and Lomatia.

Fire Response

The members of the Embothrieae vary in their responses to bushfire. Species native to areas where bushfires are a threat often have a lignotuber, a woody swelling at, or just below ground level. Lignotubers contain regenerative buds which can develop new plant stems if the above ground parts of a plant is destroyed. Lignotubers are found in most Telopea and Strangea species and in some Lomatia species.

Species native to rainforest areas usually lack lignotubers as bushfires are either very rare or totally absent from those habitats. These species rely solely on seed for regeneration.

Waratah & Relatives – Propagation

Introduction

Propagation of waratahs and their allies can be carried out by both seed and cuttings. However, with such a diverse range of species, the success of each method can be variable. Because relatively few members of the Embothrieae are widely grown, there is a lack of knowledge of the best propagation methods for many species.

To maintain desirable characteristics of a particular plant, vegetative propagation (eg. cuttings or grafting) must be used. This also applies to propagation of named cultivars.

As far as is known, grafting has not been used to any great extent with this group of plants.

Seed

As seed is shed annually, plants need to be kept under observation and seed capsules collected when they first begin to open.

Provided the seed is viable, germination of commonly cultivated members of the Embothrieae is usually reliable and no pretreatment of the seed prior to sowing appears to be necessary. There is some evidence that germination is most successful with fresh (current season) seed – this is possibly especially relevant for species native to rainforest areas.

“Damping-off” of seedlings is often mentioned as a potential problem with the NSW Waratah and may be a problem with related plants as well. Damping-off is a fungal disease which causes rotting of the stems of seedlings, particularly if the environment in which the seedlings are kept is over-wet. The disease can be controlled with an appropriate fungicide if it becomes a serious problem.

Seed can be sown in normal seed raising mixes and seedlings could be expected to appear in anything from 2-8 weeks.

Cuttings

Propagation from cuttings is a reliable method for many species in the Embothrieae. It is often preferred over propagation from seed because of both the scarcity of seed and because of the fact that cutting-grown plants will usually flower at an earlier age than seedlings.

Cuttings about 75-100 mm in length with the leaves carefully removed from the lower half to two-thirds seem to be satisfactory. “Wounding” the lower stem by removing a sliver of bark and treating with a “root promoting” hormone both seem to improve the success rate. No special propagating mixes or treatments are required.

Grafting

As noted above, grafting has not been used with members of the Embothrieae to any great extent. However, there may be some scope for using grafting with species such as the firewheel tree (Stenocarpus sinuatus) and tree waratahs (Alloxylon spp.). These can take many years to flower when grown from seed and grafting material from mature flowering plants onto seedlings of the same species may produce plants that flower at an early age. Furthermore, the plants may flower when smaller, rendering the blooms more conspicuous. This would be especially desirable in the terminally flowering tree waratahs.

The Society would welcome advice from anyone who knows of any use of grafting with this group of plants.

General Propagation

Further details on general plant propagation can be found at the Society’s Plant Propagation Pages.

Waratah & Relatives – Cultivation

Like most groups of plants, some members of the Embothrieae have proved to be easy to grow in cultivation over a wide range of climates, while others have proved to be a cause of frustration. The development of Waratah cultivars has gone some way to addressing this.

As a general rule, members of the group require the following combination of conditions:

- Excellent drainage – they will not tolerate waterlogging

- Assured moisture (especially in summer, in contrast to most other Proteaceae)- but freely draining

- Good light – at least half sun, though many species prefer some shade while young.

- Soils with at least some nutrient retaining potential, either from thick mulching or some degree of clay content (eg sandy to clay loams).

How strictly one needs to adhere to this regime varies from species to species.

- Waratahs (Telopea species) and Tree Waratahs (Alloxylon species) are the Australian representatives of the subtribe Embothriinae. All have striking red (sometimes white or yellow), showy flowers and deep green foliage, though the latter genus are far larger in size (10-30 metres high in their natural rainforest habitat). All can be temperamental and somewhat fussy when young (first two years or so), though usually become hardier once they have become established.In southern New South Wales and the ACT, several Waratah hybrids have been developed, notably Telopea “Braidwood Brilliant”, “Canberry Coronet” and “Shady Lady”. These tolerate more shade, frost and suboptimal drainage than that required for their Telopea speciosissima parent. The other parents of these hybrids are the two species from the southeastern corner of Australia; Telopea oreades (for “Shady Lady”) and T. mongaensis (for “Braidwood Brilliant” & “Canberry Coronet”).

- Lomatias have proven fairly hardy in cultivation as long as they get sufficient moisture – this is especially important if they are being grown in full sun. The genus was introduced to England in the 19th Century but is uncommonly cultivated there (or for that matter in Australia) now. In general they have white flowers which are less showy overall than their kin but instead are fascinating foliage plants with a large variety of leaf shapes seen, sometimes on the one plant, which along with their hardiness make them worthwhile garden subjects.

- In general, members of the other genera are more forgiving on gardeners; some are even hardy enough to be used as street trees (Stenocarpus sinuatus and Buckinghamia celsissima) also far to the south of their original subtropical or tropical habitat. Though few have flowerheads to match the spectacle produced by the waratahs, many are beautiful foliage plants with interesting and unusual floral forms as well. Several, however, are spectacular in their own right – a well grown ivory curl tree (Buckinghamia celsissima) in full flower will never fail to attract attention and the firewheel tree (Stenocarpus sinuatus) is arguably one of the most spectacular flowering plants in the world.

|

| A cluster of proteoid roots Photo: Brian Walters |

As might be expected with such a diverse group of plants, foliage characteristics are also quite variable. The range of foliage shapes in the genus Stenocarpus is particularly interesting and a number of species are worth growing for these characteristics alone. For example, S.cryptocarpus can produce immense, divided leaves well over a metre in length while the fern-like, juvenile leaves of S.davallioides are outstanding.

Some of these plants of rainforest origin prefer a degree of shade when young, and indeed may be used in brightly lit areas indoors for a time. This can be a great way to highlight those species with attractive foliage.

Like most members of the Protea family, the Embothrieae have a distinctive root system (“proteoid roots”) consisting of tight groupings of many small “rootlets”. These are believed to enable the plants to more efficiently take up nutrients from the nutrient-deficient soils where many of the species occur naturally. In cultivation this means that the plants can be adversely affected by fertilizers, particularly phosphorus. It is generally recommended that Proteaceae be fertilised only with low-phosphorus, slow-release fertilisers or not be fertilised at all.

Currently, only few members of the Embothrieae are seen commonly in cultivation. Hopefully this will change in the future. However, several (such as the three Strangea species) are probably of limited horticultural merit and will probably only be grown by enthusiasts and by Botanic Gardens.

Growing the Sydney Waratah

Max Hewett

The following article is reproduced from the September 1982 issue of the Society’s journal Australian Plants. Although now some years old, the methods described has been proven to be successful and remain an excellent guide to the cultivation of Telopea speciosissima.

Experience indicates there are certain guide lines to the production of healthy specimens of waratah, Telopea speciosissima, under a wide range of soil types. The following factors are to be considered, the first four being of major significance.

1. Freedom From Root Competition

The late Frank Stone, founder of Waratah Park, Bilpin, maintained that anybody could grow waratahs providing they maintained the soil adjacent to the plant in a state of fine tilth. I have personally tested his statement on many occasions in my garden and confirm its accuracy.

After plants have been established two years or so and have formed a lignotuber I have cultivated to shovel depth (approx. 200 mm) from the plant stem to 1 metre radius. This has been done approximately twice per year and the plants have never failed to respond with new vigour and new growth at or near ground level. Plants not so treated have declined in vigour to bare stems carrying few leaves and few, if any, flowers. Some plants which had been overgrown with foliage from adjacent shrubbery and had been dormant for ten years or more have responded with new growth when freed from leaf competition and given the above soil treatment.

2. Depth of Soil to Impenetrable Layer

Waratahs are most successfully grown where the main root stem can penetrate freely to a metre or more (refer also item 4). Although I have observed specimens growing and flowering in a bed made up of about 150 mm depth on a shelf rock, almost daily watering was required.

3. Soil Type

Although specimens occur widely in the Hawkesbury Sandstone country of the Sydney area, the standard of foliage and flower development, except after fires followed by heavy seasonal rains, does not approach the quality of stands in the rich basaltic loams at Bilpin and other Blue Mountains areas, the deep brown loams with laterite association found near Terrey Hills, or the brown loams on shale in some locations along the Putty Road north of the Colo River. In the deep, rich, brown, volcanic loams of the Dandenongs near Melbourne, the Sydney waratah is grown extensively and to perfection for the flower trade. In the poorer soils near Melbourne, however, few satisfactory results have been achieved. I had several reports of specimens flourishing in the volcanic loams of North Island, New Zealand, producing up to 100 flowers per plant.

|

| NSW Waratah (Telopea speciosissima) Photo: Brian Walters |

From the above it would seem to be obvious that soils of the heavier texture offer the most likely condition for vigorous growth. In fact, gardeners in rich soil areas have little difficulty in establishing healthy plants, whereas those in sandy areas are frequently disappointed with their performance. This must be related to factors 4 and 6 (see below) and suggests that plants grown in lighter soils should have their nutrient and moisture supply augmented for best results.

4. Availability of Soil Moisture and Drainage

One-time Native Plant nurseryman, Jack Twyford of Thornleigh, who grew waratahs very well in heavy clayey loam, made the following comment to me: “Waratahs do best when roots are kept cool and foliage is in full sun”.

My own experience would seem to confirm this. I believe in this regard that ideal conditions prevail where an impenetrable layer, as noted in 2 above, provides the moisture trap… but a word of caution would be appropriate. Ensure that drainage of subsoil is adequate to prevent waterlogging in prolonged wet periods.

Although the species seems to be relatively resistant to attack by root rot fungus (Phytophthera cinnamomi), I have observed several plants which gave the appearance of such fungal attack. These were all in light soil areas over sandstone, and one might presume that subsoil drainage could be locally deficient. Perhaps the faster penetration of water through sandy soil and consequent raising of water table could represent a hazard.

5. Aspect and Exposure

Despite comments in 4 above, I have grown and otherwise observed many plants growing reasonably in broken sun, so I feel this factor is only of minor significance. One grower reported cases of leaf scorch, which perhaps could be attributed to his rich subsoil with ample subsoil moisture producing lush early growth with vulnerability to hot early seasonal conditions.

|

| Telopea spesiosissima cultivar ‘Wirrimbirra White’ Photo: Brian Walters |

6. Fertilising

Although I personally do not use fertilisers on my waratahs, my observations of other growers’ plants indicated favourable response to light applications. As noted in 3 above, the major necessity arises in gardens in the light soil range. The time for application is when new growth first appears in late winter/early spring..

7. Mulching

I find a heavy mulch of leaf litter advantageous providing the lignotuber is kept free and open. The mulch is dug in when cultivating (see 1 above).

8. Pruning

Established plants benefit greatly from pruning.

As a general rule, early cutting of the flower stems to at least half the pre-flowering growth increases the number of flowering stems for the following year. Where mature plants have aged to a number of long bare canes, it is advantageous to cut them away completely to the lignotuber immediately after flowering. Some growers may be apprehensive of removal of all canes simultaneously. While I have not experienced ill effects from this treatment I appreciate their concern and suggest, as a first up, the operation could be spread over two seasons.

9. Watering

The subject of soil moisture is reasonably covered above. If, however, hand watering is applied, I would suggest the object should be to restore subsoil moisture when dry seasons would affect growth in the growing period, and would best be achieved with infrequent heavy soakings by the trickle method. On the other hand, no adverse effect could be expected from occasional general garden waterings. Waratahs go into dormancy in Sydney in late autumn and commence new growth generally in early late winter/early spring (see 6 above). Watering should not be applied during this period, unless only of a light nature.

10. Insect Attack

On certain plants in my garden insect attack to the flower buds occurs regularly each year. This I believe is from what is known as the Waratah Beetle, and has the effect of reducing the number of developed flowers on affected plants by up to 50%. All my efforts to date to overcome this problem have been in vain, the buds having been damaged before the attack was noticed. Further research is needed on this problem.

Waratah & Flannel Flower Study Group

This Group was formed in 2011 with the aim of studying the cultivation and propagation of Waratahs (Telopea species) and Flannel Flowers (Actinotus helianthi), so that more species could be seen in gardens.

Although the group is now closed, newsletters and other information is still available and can be found at the following links:

***Click here to go to the Study Group’s Newsletter Archive***

Waratah & Relatives – Further Information

Most books dealing with Australian native plants will contain useful information on the botany and horticulture of various members of the Embothrieae. Some of the most detailed references are listed below.

Books:

- Elliot W. R and Jones D (1980-1997), The Encyclopaedia of Australian Plants, all volumes, Lothian Publishing Company Pty Ltd, Melbourne.

- Nixon P (1987), The Waratah, Kangaroo Press.

- Wrigley J and Fagg M (1989), Banksias, Waratahs and Grevilleas, Collins Publishers Australia.

Journals:

Several issues of the Society’s journal “Australian Plants” are particularly useful for those interested in waratahs and their cousins.

- Vol.1 No.1 December 1959; How to grow Waratahs; The genus Telopea.

- Vol.5 No.39 June 1969; Waratahs – How do they grow?.

- Vol.5 No.40 September 1969; Telopea truncata (Tasmanian Waratah); Growing Tasmanian Waratahs.

- Vol.11 No.92 September 1982; Growing the Sydney waratah.

- Vol.12 No.96 September 1993; Lomatia.

- Vol.12 No.99 December 1986; Propagation of Telopea.

- Vol.14 No.109 December 1986; Lomatia: The genus.

- Vol.14 No.114 March 1988; Extensive coverage of cultivation and propagation of Telopea.

- Vol.16 No.128 September 1991; Buckinghamia celsissima.

- Vol.18 No.141 December 1994; Growing waratahs.

- Vol.18 No.147 June 1996; New waratah cultivars.

- Vol.18 No.148 September 1996; Stenocarpus: The genus; Waratahs grown in alkaline soils

- Vol.19 No.156 September 1998; Lomatia tasmanica, oldest tree in the world; Yellow form of Telopea truncata.

- Vol 20, No.161 December 1999; Alloxylon Tree Waratah.

- Vol 20, No.164 September 2000; Waratahs in the Olympic Bouquet; Gembrook Waratah.

- Vol 21, No.172 September 2002; Opisthiolepis heterophylla, history, description and cultivation.

Internet:

- Waratah & Flannel Flower Study Group newsletters – recent issues are available here.

- The website of the now closed Waratah and Flannel Flower Study Group is an excellent resource for the various varieties and cultivars of these plants.

- From Pod to Pod – A Tale of Lomatia

- The Genus Lomatia

- Growing Native Plants – a series of plant profiles by the Australian National Botanic Gardens; includes a number of Embothrieae.

- Growing Waratahs

- The Magnificent Tree Waratah

- The Queensland Tree Waratah

- Tree Waratah; Is this name wrongly applied to Alloxylon flammeum?

- Will the Waratah Ever Fulfil its Potential?

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)