Eremophila and its Relatives – Background

Introduction

Eremophila is a large genus of plants closely related to Myoporum. They were formerly classified within the plant family Myoporaceae but that family is now obsolete and has been absorbed into the Scrophulariaceae, which is distributed throughout temperate and tropical climates and consists of small to medium shrubs or small trees. Together with Myoporum and a few other genera, Eremophila is placed within the Tribe Myoporae, which mainly occurs in Australia and the South Pacific islands, but also in other areas including South Africa, Asia, Hawaii and the West Indies. There are currently six genera in the Tribe:

- Bontia, comprising a single species (Bontia daphnoides) which occurs in the Carribean

- Calamphoreus, comprising a single species (Calamphoreus inflatus) which occurs in Western Australia (previously known as Eremophila inflata)

- Diocirea, comprising 4 species occurring in Western Australia

- Eremophila, comprising at least 250 species, occurring throughout Australia in all mainland states.

- Glycocystis, comprising a single species (Glycocystis beckleri) which occurs in Western Australia (previously known as Myoporum beckleri)

- Myoporum, comprising about 30 species occurring in Australia, New Zealand, the Pacific Islands, east Asia and Mauritius.

Some authorities place Calamphoreus and Diocirea in Eremophila but the two genera remain separate in the Australian Plant Census, which ANPSA accepts as the authority on Australian plant taxonomy.

Australian genera in the Tribe Myoporae are concentrated in the semi-arid and arid regions with the largest number of species being located in Western Australia. Eremophila is by far the largest of the Australian genera and the one most commonly encountered in cultivation. Some of the features of that genus are described below.

Characteristics of Eremophila

Eremophila species are commonly called “emu bushes”. All species are endemic to Australia and they produce fleshy fruits which are often eaten by birds and animals. The common name derives from the erroneous belief that the fruits are eaten by emus and that the chemical changes that occur in the seed during digestion enhance the rate of seed germination after excretion. In fact, the fruits of relatively few species are eaten by emus and the time of passage through a bird is insufficient to influence germination.

The plants are also known as “poverty bushes” because of the ability of many of them to survive in very dry, inhospitable environments. Most are found in areas receiving less than 250mm rain per year.

Eremophilas are usually small to medium shrubs although a few may be large shrubs or small trees (eg. E.bignoniiflora) There are a number of fully prostrate species. Their range in growing forms, interesting fruit, range of leaf forms (from grey to bright green) and the presence of brightly coloured calyces in many species makes them excellent plants for the home garden.

The foliage of some species is toxic and stock poisonings have occurred (eg. E.freelingii, E.latrobei). Some other species are useful as fodder plants (eg. E.bignoniiflora, E.oppositifolia).

Eremophilas have also been valued for medicinal and cultural purposes by Aboriginal people. For example, E.longifolia was important to the Adnyamathanha people of the northern Flinders Ranges1. More recently, traditional uses of E. alternifolia leaves, infusions and handmade leaf-pastes have been reviewed in traditional Aboriginal practice for their use to treat infections of eyes and skin, and to speed healing of wounds2.

Those species which occur in the harshest of climates have developed methods to cope with the severe conditions. Many have greyish, hairy foliage which reflect the sun’s rays while other have a shiny, sticky coating on the foliage as a protection against drying winds. Many in these regions also respond to rain by flowering within a few weeks of significant falls.

The flowers of Eremophila are more or less tubular in shape with upper and lower lips. They are reasonably large and often very colourful and are sometimes spotted. In some species the corolla may also be subtended by a large and attractive calyx. These features have resulted in a number of species being cultivated as ornamental plants. Flowers occur in the leaf axils. The flowers contain nectar. Red, yellow and orange flowered species are adapted for pollination by honey-eating birds, whereas those with pink, white or mauve/purple flowers are more usually adapted for pollination by insects.

Following flowering, 1 to 12 seeds develop in a fleshy or dry indehiscent fruit.

Footnotes:

- Reported by Rosemary Pedler in the Eremophila Study Group Newsletter, December 1994.

- Israt, B et al (2016): Antibacterial constituents of Eremophila alternifolia: An Australian aboriginal traditional medicinal plant, Jnl of Ethnopharmacology, April 2016 – see also Eremophila Study Group Newsletter 114 of June 2016.

Eremophila and its Relatives – Propagation

Introduction

Most emu bushes and their relatives are propagated by cuttings or other vegetative means (such as grafting). Experience with propagation of Calamphoreus, Diocirea and Glycocystis species is limited but it can probably be assumed that similar requirements to those used for Eremophila and Myoporum could be applied.

Seed

Under field conditions, seeds of Eremophila germinate naturally in response to heavy rain. However, under horticultural conditions, seeds of Eremophila are often difficult to germinate and it is reported that germination is sometimes more reliable from fresh seed, although it is also known that seed will retain its viability for many years1. However, when using either fresh or older seed, germination is usually slow and can take anything from a few weeks to well over a year. Obviously, seed trays should not be discarded in haste! However, because of these problems, propagation by cuttings or grafting is preferred. Myoporum seeds usually germinate more reliably than Eremophila but again, cuttings strike readily for most species and this is the preferred method.

Because of the horticultural potential of Eremophila, there has been considerable effort put into improving germination reliability of seed of this genus. Several of these methods have been somewhat successful and are outlined below.

- Extraction of Eremophila seeds from fruit

It is possible to achieve germination of Eremophila seeds by sowing the fruits whole, but this gives very inconsistent results. Extraction of the seeds from the fruits prior to sowing is far more effective, but this is time consuming, requires considerable practice to avoid damage to the seed and, even then, reliable germination may depend on other factors such as the age of the seed, the possible presence of inhibitors and temperature. The following method of extracting seeds has been reported as being effective:

-

- Thoroughly dry the fruit.

- Place the dried fruits in a small engineer’s vice (one with the metal jaws) such that either end of the nut is pressed against the jaws (use forceps to align the fruit, if necessary).

- Tighten the vice until the nut cracks – usually the seed(s) will drop out intact.

Extracted seed usually germinates well by conventional sowing methods in a standard seed raising mix. In some cases, it has been found that removal of the testa from the seed (the thin, skin-like coating surrounding the seed) improves germination. There appears to be conflicting evidence on the influence of the age of the seed on germination, or the impact of chemical inhibitors2.

Further information on experiments on the germination of Eremophila seed can be found in A Study of Eremophila Seed Germination by Paul Rezl on the “Propagation – Seed Germination Study” tab.

- Use of smoke to assist germination of Eremophila

The use of smoke to stimulate germination of seeds has been reported for a number of Australian plant genera. General information on the use of smoke to improve seed germination is available in the article Smoke Stimulates the Germination of Many Western Australian Plants (see “Further Information” tab) and from the Regen 2000 web site. Germination of seeds within whole fruits may also be improved by smoking (direct smoke, or using smoke water) but, again, yield is low.

Cuttings

Most members of the family strike readily from cuttings of hardened, current season’s growth. Cuttings about 75-100 mm in length, with the leaves carefully removed from the lower two-thirds seem to be satisfactory. “Wounding” the lower stem by removing a sliver of bark and treating with a “root promoting” hormone, e.g. IBA3000 both seem to improve the success rate.

Grafting of Eremophila

Many Eremophilas are difficult to cultivate in humid areas and/or are difficult to strike from cuttings but, because of their ornamental potential, people continue to make the effort. One method which is reasonably successful is the grafting of desirable species onto hardier root stocks. The best root stocks appear to be Myoporum species. M. parvifolium, M. montanum, M. insulare and M. acuminatum have been used successfully with a large number of Eremophila scions, as has Eremophila denticulata ssp. trisulcata. Grafting has certainly improved the hardiness of many species and has been more reliable than grafting of difficult-to-strike varieties.

General Propagation

Further details on general plant propagation can be found at the Society’s Plant Propagation Pages.

Footnotes:

- Seed Notes for Western Australia, No. 5 – Eremophila.

- Richmond, G and Chinnock, R (1994): Seed germination of the Australian desert shrub Eremophila (Myoporaceae), The Botanical Review, 60(4): 485-503, October 1994.

The Eremophila Study Group has developed an image database which aims to illustrate all Eremophila species, hybrids and cultivars, with photographs showing flower and foliage characteristics and basic information on plant size and flower colour.

As there are over 250 species of in the genus, the database is a work-in-progress and it will be some time before all species and forms are included. The database can be viewed at the following link.

Eremophila and its Relatives – Cultivation

Cultivation of Eremophila

Among the Australian members of the Myoporum group of plants (Tribe Scrophulariacae, formerly Myoporae, of the Scrophulariaceae family), Eremophila (emu bush) has received by far the greatest horticultural attention. Emu bushes have considerable potential for general cultivation, particularly in areas with relatively dry summers. As our climate changes, these areas will become more widespread nationally.

Once established, Eremophilas are very drought tolerant and rarely require artificial watering. With many different forms, growth habits and flower colours, Eremophilas can be used for many different purposes in the garden. In addition, the flowers of most species produce nectar and are excellent for attracting birds.

In cultivation, all species of Eremophila perform best in well-drained soils. They rarely succeed in continually wet soils. Shallow clay soils can present problems but if garden beds are built up to 300-600mm, greater success is experienced. Many species tolerate alkaline soils. Eremophilas are generally at their best in open, sunny positions with good air circulation (i.e. not crowded by adjacent plants). Using grafted plants will also increase longer term reliability in the garden.

Many species are adaptable to humid climates but those species with hairy foliage may be subject to fungal diseases is those areas. The impact of fungus can be minimised by:

- growing plants in pots that can be moved into a sheltered position during heavy rain;

- pruning off mouldy foliage when it appears;

- selective pruning to decrease the density of foliage;

- choosing non-grey species for the garden; or

- planting in areas which have greater wind flow

Emu bushes are not demanding as far as fertilizing is concerned but they do respond to applications of slow release fertilizer applied after flowering. If desired, the plants can be pruned back by about one third after flowering to promote a bushy habit of growth. Some species can be pruned quite hard.

Cultivation of other members of the Tribe Myoporeae

There has been some limited cultivation of Calamphoreus inflatus and Glycocystis beckleri but there appears to be no information regarding cultivation of the four Diocirea species. However, all six of these species occur in south Western Australia and it can be assumed that they would require similar conditions to Eremophila that occur in the same region (i.e. they can be expected to suited to climates with a dry summer, they will be less successful in humid temperate areas and they will be very difficult in tropical and tropical regions).

Myoporum has been more widely cultivated and some species are well known in general horticulture (e.g. Myoporum floribundum, M.parvifolium, M.insulare). Although generally not as spectacular as the Eremophilas, they are usually hardy and reliable. However, Myoporums occur in a range of habitats ranging from arid to tropical. Some, like M. montanum are widespread over that whole range of climates. Selection of plants for cultivation in a particular district should therefore consider the climatic conditions that the species experiences in nature. Myoporums appear to be adaptable to a range of soils, provided they are well drained.

As noted in the “Propagation” tab, Myoporum can also provide a handy root stock for grafting Eremophila.

Eremophila Seed Germination Study

To date, horticulturalists have been unable to grow Eremophila reliably from seed without recourse to expensive hormones or tissue culture. As academic research into this is limited to two PhD theses from the 1970s and 1990s, the Eremophila Study Group initiated formal research with its selected research partner, the University of Queensland. The Study Group now has has three research grants to explore different aspects of Eremophila seed germination. The research aims to explore different aspects of germination with the broad aim of determining germination triggers and enabling plants to be grown reliably from seed for both revegetation and horticultural development purposes. More details of the current projects (which started in 2022) can be found on the Research section of the Study Group’s website.

Prior to this, the Study Group published a semi-formal seed germination study in its August 1998 Newsletter.

The following article is reproduced from the August 1996 newsletter of the Eremophila Study Group.

Note that comparison of the viability between wild and commercial sources of seed was not an objective of this study. Accordingly, the identity of the commercial seed supplier has been deleted from the original article because a) there is no suggestion that seed from any other commercial source would have achieved better results and b) there was no duplication of species between the commercial and Mullewa sources.

A Study of Eremophila Seed Germination

Paul Rezl

Eighteen species of Eremophila from two different sources were sown on 14 April 1996. Most of them (11) were collected from a property near Mullewa, Western Australia in September/October 1995. These were:

| E.clarkei | E.mackinlayi |

| E.compacta | E.oldfieldii |

| E.eriocalyx | E platycalx |

| E.forrestii | E.serrulata |

| E.fraseri subsp. galeata | E.”spuria” |

| E.longifolia |

Another seven species were obtained from a commercial seed service in February 1996 but the age of the fruits was unknown. These were:

| E.cuneifolia | E.maculata |

| E.densifolia | E racemosa |

| E.divaricata | E.spectabilis |

| E.laanii |

Seed Extraction

It is known that Eremophila seeds are locked in woody fruits and for germination to take place they need to be released. This is, in most cases, quite a laborious process, but nevertheless the most important one. Eremophila fruits exhibit a remarkable diversity, not only in the shape and size (ranging from as little as 2 mm in E.densifolia to 15 mm in E.maculata), but also in the internal structure. Some fruits are corky inside and the seed is quite loose but in many species the inside is more or less woody.

Fruits consist of four chambers and these contain up to 12 seeds according to Richmond and Osborne (“Australian Plants” No. 134) but in practice I have never found more than six fully developed seeds per fruit. Seeds are elongated, approximately 2-6 mm long. They are covered with a thin skin-like testa. To release the seeds from fruits it is necessary to open each of the four seed chambers and that means basically splitting the fruits in halves and quarters. I use a board made of soft wood (pine – any offcuts would do), a light hammer and a Swiss army knife (or similar). Fruits are placed in small dents on the board for better stability and, while holding the edge of a knife somewhere close to the central seam of the fruits, they are split longitudinally. This needs to be done very carefully at first as different species require different force. Some seeds are inevitably damaged during the process.

Sometimes only a part of the seed is exposed and it is good to loosen it up by scraping off the surrounding shell using whatever is handy. Details on seed extraction are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1 – Seed Extraction

|

Species

|

Avg. No. of Seeds in the Fruit

|

Structure of the Fruit

|

Ease of Seed Extraction

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

E.clarkei

|

|

semi-hard

|

medium

|

|

E.compacta

|

|

soft

|

easy

|

|

E.cuneifolia

|

|

soft

|

easy

|

|

E.densifolia

|

|

soft

|

very difficult, tiny fruit

|

|

E.divaricata

|

|

semi-hard

|

medium, seed very small

|

|

E.eriocalyx

|

|

very soft, corky

|

very easy

|

|

E.forestii

|

|

hard

|

medium

|

|

E.fraseri subsp. ‘galeata’

|

|

hard

|

medium

|

|

E.laanii

|

|

hard

|

medium

|

|

E.longifolia

|

|

very hard

|

very difficult

|

|

E.mackinlayi

|

|

hard

|

difficult

|

|

E.maculata

|

|

very hard

|

medium

|

|

E.oldfieldii

|

|

semi hard

|

easy, low seed count

|

|

E.platycalyx

|

|

soft, brittle

|

medium

|

|

E.racemosa

|

|

hard

|

medium

|

|

E.serrulata

|

|

hard

|

medium

|

|

E.spectabilis

|

|

hard

|

medium

|

|

E.’spuria’

|

|

soft, brittle

|

easy

|

Seed Sowing

Soil less propagating mixture was used for sowing. It is based on Lignocel (milled coconut shells which are compressed into brick-like blocks) and perlite in the rate of 3:1. I use this universally for all sowings. It is similar to peat/perlite mix but it has better water holding capacity and the structure is more open, doesn’t compact easily and unlike peat, absorbs water readily even when dry. As a result, young seedlings root very well in this mixture.

I do not sterilise the mix; it is generally treated with fungicide. In this case a new product, PolyversumTM, was used for the first time. It is a new generation biofungicide that works on the wide spectrum of soil-borne diseases. The active agent is the fungus Pythium oligandrum which is naturally present in small quantities in the soil. This “friendly fungus” lives in symbiosis with the root system of the plants. As stated by the manufacturer, the product is non-chemical and therefore completely harmless. Remarkable is the long storage capacity of 1O years (provided it is kept dry). When preparing the propagating mixture a Lignocel block must be water saturated first and this was done by adding 5 litres of water to the compressed block. In this case 0.05% Polyversum was used in order to inoculate the substrate. Seeds were treated with Polyversum prior to sowing and sown immediately in small containers only lightly covered. Containers were watered by soaking in 0.05% Polyversum and placed in the propagating box with the temperature regime of 25o C day/5o C night in order to simulate the oscillating temperatures inland where most eremophilas grow. As I do not have a growth room or a thermostat, the box was placed in a fridge every night and removed in the morning for the period of first two weeks from the date of sowing. The propagating box was then left on 25o C permanently. Results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2 – Seed Germination

|

Species

|

No. of Fruits Used

|

No. of Seeds Sown

|

First Seedling (days)

|

No. of Seeds Germinated

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E.clarkei

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.compacta

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.cuneifolia

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.densifolia

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.divaricata

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.eriocalyx

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.forestii

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.fraseri subsp. ‘galeata’

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.laanii

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.longifolia

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.mackinlayi

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.maculata

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.oldfieldii

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.platycalyx

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.racemosa

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.serrulata

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.spectabilis

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.’spuria’

|

|

|

|

|

Results and Observations

Of the total of 132 seeds sown, 49 have germinated and that means 37% germination in total. I have deliberately not counted the germination for each species because the number of seeds sown varied, in some cases being as little as 1.

Generally all species from Mullewa have germinated. They showed much better germination rate (48%) than the seed from the commercial source (16%). Three species did not germinate and they were all from the commercial source.

Germination was rapid. Most of the germination occurred in the second and third week from the date of sowing and after one month I considered it to be complete.

With two seeds of E.maculata which refused to germinate in spite of all efforts, I have decided to remove the testa. It was carefully peeled off and both seeds germinated immediately.

Pots with seedlings were placed under fluorescent lights with a 14 hour day/l0 hour night cycle. They were growing vigorously as expected and quickly showed some signs of nutrient deficiency. Because the propagating mixture is very low in nutrients, I started to apply regular doses of complete fertiliser and the seedlings responded immediately by strong healthy growth.

At this stage two applications of 0.05% Polyversum were applied to the seedlings (watering) as recommended by the manufacturer.

Seven seedlings were lost before the first repotting, possibly due to an airborne fungal infection, drying out or natural weakness. First repotting was done approximately one month from the date of sowing and most of the seedlings had 2-4 pairs of leaves. Potting mix was based on loam/peat 1:1 which I am using for all of my plants. I have noticed a very healthy, well developed root system in all seedlings.

There were no losses after the first repotting and all of the plants (42) are healthy and growing well at the time of writing.

Conclusion

Seed extraction is the single most effective method of sowing Eremophila seed. Other methods mostly use fruits and not the seed for sowing and therefore are much less effective. Many fruits contain no viable seeds and these are eliminated by the extraction method.

Several germination delay mechanisms other than the physical one (which, in all cases, is the impervious woody fruit) have been observed. These are the effect of temperature (oscillating temperatures promote germination) and the presence of inhibitor in the seed testa. These two mechanisms are not developed in all species and many germinate under the constant temperature. Most seeds will germinate without the removal of testa but in some cases as demonstrated on E.maculata this procedure is very helpful.

Contrary to what has been previously published, fresh seeds germinate better than old.

Treatment of seed, soil and seedlings with Polyversum has proved to be very beneficial. Root systems on the first repotting were well developed. Plants appear to be very compact with short internodes and many side shoots. Polyversum seems to stimulate the growth through the root tissue. I sincerely recommend it for testing with many other Australian native plants.

Sowing of Eremophila seed as described above can be a good alternative to vegetative propagation and can be used for breeding new cultivars and propagation of the rare species.

Eremophila Study Group

The Eremophila Study Group is one of a number of Study Groups within the Australian Native Plants Society (Australia). Its aim is to further knowledge about the cultivation, propagation and conservation of members of the genus Eremophila, which are commonly known as emu bushes. As in all study groups, the members’ work is carried out in their own homes and gardens and in their own spare time.

Further information about the Study Group, its activities and access to the newsletter archive can be found at the link below.

Eremophila and its Relatives – Further Information

Most books dealing with Australian native plants will contain useful information on the botany and horticulture of Eremophila and Myoporum but other members of the family are less well documented. Some of the most detailed references are listed below.

Books:

- Boschen, N, Goods M and Wait R (2008), Australia’s Eremophilas, changing gardens for a changing climate, Bloomings Books, Melbourne.

- Brown, A and Buirchell B (2021, 2nd edition), A Field Guide to the Eremophilas of Western Australia, Simon Nevill Publications, Perth.

- Chinnock, R.J (2007), Eremophila and Allied Genera: A Monograph of the Myoporaceae, Rosenberg Publications, Kenthurst, New South Wales.

- Elliot, W. R and Jones D (1984), The Encyclopaedia of Australian Plants, Vol.3, Lothian Publishing Company Pty Ltd, Melbourne.

- Elliot, W. R and Jones D (1984), The Encyclopaedia of Australian Plants, Vol.6, Lothian Publishing Company Pty Ltd, Melbourne.

- Richmond G and Ghisalbertii E (1994), The Australian Desert Shrub Eremophila (Myoporaceae): Medicinal. Cultural , Horticultural and Phytochemical Uses, Economic Botany 48(1): 35-59, 1994.

- Society for Growing Australian Plants – South Australian Region (1997), Eremophilas for the Garden, SGAP (SA Region).

- Wait, R et al (2021): Growing Eremophila, published by Russell Wait. Hardback, 504pp. Available from the author via eremophilabook@gmail.com and several bookstores.

Journals:

Several issues of the Society’s journal “Australian Plants” are particularly useful for those interested in Eremophila.

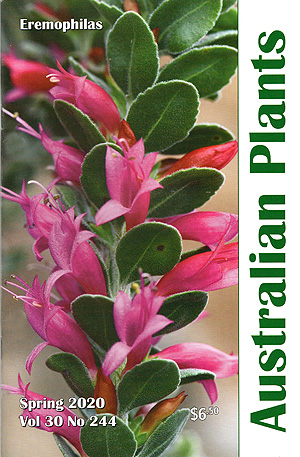

- Vol 30, No.244 Spring 2020; Special issue on the genus Eremophila and its uses in the garden

- Vol 25, No.199 June 2009; Growing Eremophilas in Western Sydney, From the desert to the garden – Eremophilas

- Vol 24, No.190 July 2007; Review of Eremophila and Allied Genera

- Vol 23, No.185 December 2005; Eremophila mitchellii in profile

- Vol 21, No.171 June 2002; Hardy Cultivars

- Vol 20, No.163 June 2000; Eremophila as cut flowers, Eremophila in floraculture, Eremophila seed germination

- Vol 19, No.154 March 1998; Emu Bush: How to grow and conserve Eremophila, Eremophila as cut flowers, My favourite eremophilas

- Vol 17, No.134 March 1993; Eremophila germination studies.

- Vol 15, No.120 September 1989; Cultivation and propagation of Eremophila in Sydney.

- Vol 13, No.103 June 1985; Eremophila in Alice Springs.

- Vol 12, No.100 September 1984; Eremophila in Hobart.

- Vol 12, No.93 December 1982; Numerous articles on botany, propagation and cultivation.

Internet:

- Eremophila Study Group newsletters – recent issues are available here.

- Eremophilas in San Diego

- Eremophila: The Emu Bush – A review of emu bush cultivation

- Eremophila and Pollinators

- Eremophila debilis – article by the National Botanic Gardens

- Eremophila subfloccosa – article by the National Botanic Gardens

- Eremophilas in Containers

- Eremophilas; the desert lovers by Ian Fraser – overview of the genus with many photos.

- Germination Trials with Eremophila species

- Grafting Grey-leafed Eremophilas in Melbourne

- Growing Eremophilas in the Dandenongs

- Myoporum bateae – article by the National Botanic Gardens

- Myoporum floribundum – article by the National Botanic Gardens

- Smoke Stimulates the Germination of Many Western Australian Plants, by K.Dixon and S.Roche – contains useful information on research into many plant genera.

- The Weeping Emu Bush – Eremophila longifolia

- Tolerance of Eremophilas to Heavy Frost

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)