Rediscovering Grevillea rosmarinifolia

Peter Olde

The following article is reproduced from the newsletter of ANPSA’s Grevillea Study Group, March 2000. Peter is the leader of the Study Group.

One of the few plant species actually described by Allan Cunningham was Grevillea rosmarinifolia which appeared, along with several others, in Barron Field’s Geographical Memoirs of New South Wales (Pp.326-329).

Although Cunningham was a capable botanist himself and collected hundreds of species unknown to science during his time in Australia and New Zealand, most of his specimens and descriptive work was sent to Robert Brown who used his manuscripts and often even his manuscript names in his Supplementum Primum Prodromi Florae Novae Hollandiae published in London in 1830.

Cunningham’s Latin description of Grevillea rosmarinifolia was accompanied by the words “….A shrub of robust growth, and with reddish showy flowers. Banks of the Cox’s River.”

The rediscovery of this plant at the Type locality has been one of the holy grails of New South Wales botany, especially those associated with the genus Grevillea.

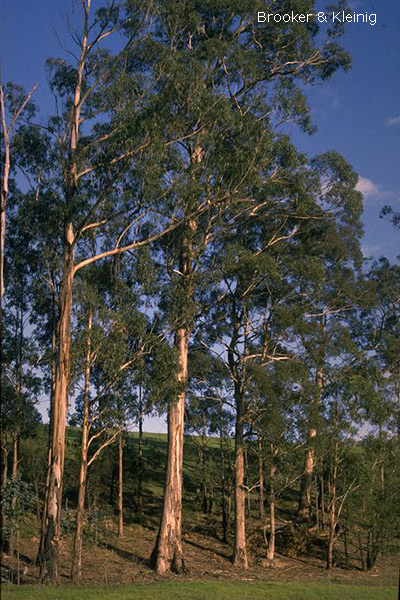

The “type” form of Grevillea rosmarinifolia

Photo: Brian Walters

For information on the ‘type’ form of a species, see the footnote box

Grevillea rosmarinifolia is not a rare species, as circumscribed by McGillivray (1993). This circumscription is very broad and encompasses several population-based distinctive taxa. The species sens. lat. will soon the subject of a detailed revision. It is distributed on a wide range of soils ranging from basalt to granite and desert sands over a large area of both New South Wales and Victoria. Yet the form from the Cox’s River differs from all the others in having longer and broader, linear to narrowly lanceolate leaves.

There are few recorded collections of this taxon. The only specimens are those of Cunningham, collected in 1822. However, in a Catalogue of Plants cultivated at the Botanic Gardens, Sydney,New South Wales, January 1828, Charles Fraser indicates that G.rosmarinifolia was introduced there by himself in 1825. Indeed Fraser died while returning from Bathurst with a cartful of living plants in 1831.

The particular form of this species next appears between 1827-1828 in Robert Sweet’s Flora Australasica as an illustration of a plant growing at Mackay’s Clapton Nursery (United Kingdom). Sweet also informs us that it was first introduced at the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew, without explicitly stating by whom and how the plant was communicated.

In 1829, there appears another illustration from a “weak and starved” specimen at the Hackney Nursery, London. This can be found in Conrad Loddiges’ Botanical Cabinet: 15 where we are informed that the species had been in cultivation in England “since c. 1820”.

Subsequent sources give variable dates of introduction. Sweet (1827) says 1821 while Loudon (1830) says 1824, the latter date being the most likely since Cunningham did not collect it until 1822 as far as I can make out.

In Europe, Grevillea rosmarinifolia flourished in horticulture. There is evidence of its cultivation in Dusseldorf 1834, Florence 1854-55, Amsterdam 1857 and even Russia at Aksakov, 1860.

However, things on the ground at home were not too good. In a letter to Richard Cunningham accompanying the Type Sheet at K, Allan Cunningham recommends a visit to the grassy flat of the military depot (now known as Glenroy) where Governor Macquarie rested in 1815. Grevillea rosmarinifolia was to be found “on the flat at Cox’s River just below the Military depot on the immediate bank of that ?stream where also are to be observed G.sulphurea and G.canescens ….. if not destroyed by cattle”.

The place must once have been a haven for grevilleas. In a diary entry dated Friday 11th April 1817, Cunningham writes “At this river we first observed granite, of which its bed is composed. Grevillea acanthifolia and Grevillea asplenifolia (sic!), …., grow on the banks of this river in the greatest luxuriance.”

Several searches of the Type locality in the late 1960s and early 1970s failed to locate any plants of G.rosmarinifolia. Certainly no new collections have appeared in the specimen base at NSW, although specimens that differ in minor ways have been collected at Hampton and on the Kowmung River at Tuglow.

Then in a brief note that set interest soaring, D.J. (Don) McGillivray (1975) stated that “in August 1969, [he] observed a specimen of the type form of G.rosmarinifolia growing outdoors, beside a building in the Edinburgh Botanic Garden”.

Cuttings from the plant were sent to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney, and specimens have been established in a number of gardens and some nurseries in New South Wales and Victoria. It is distinguished from other forms of the species by its longer, broader leaves, c. 2.5-4 cm long and 2-3 mm wide.

The very thought of a presumed-extinct Australian plant form being re-discovered at Edinburgh nearly half a world away and 1.5 centuries after it had presumably disappeared from its natural habitat was scarcely believable; but to have material returned from there to be re-introduced perhaps into the Australian wild was inspiring and exciting to say the least. Not only that but the re-discovery was such a fluke in itself.

The interpretive label on the living plant at Edinburgh Botanic Garden was Grevillea lanigera, and perhaps the only person in the world capable of recognising the taxon and its correct name and significance at that time happened upon it there by chance. The origin of the plant at Edinburgh is unclear. It may have been cloned from the original material at Kew which was communicated probably by Cunningham.

However, it may have been sent independently by Fraser, who was also a Scotsman and sent large amounts of material to Scotland during his tenure at the Sydney Botanic Gardens. For Fraser, indeed, this was part of his job description, as from 1823, he was officially known as “Superintendent Sydney Botanic Gardens” where he worked to collect and grow indigenous plants for the garden and to stabilise them for long voyages in a “plant cabbin” to grace the gardens of the King and also as a clearing house for exotics and fruit vines being introduced to the colony. In 1826, William Jackson Hooker published a description of Grevillea pubescens (syn. G.baueri subsp. baueri) from a specimen grown from seed sent to him at Glasgow by Charles Fraser in 1822, flowering there in 1825.

Seed was also sent by Fraser to Dr Graham at Edinburgh Botanic Gardens. The truth is that we do not really know how or from what clone the Edinburgh material arose but we can surely be grateful that it had been maintained so successfully in cultivation for so long and that plants continued to survive outdoors in such a climate.

In Australia, meanwhile, the search for topotypical material continued. Between 1990 and 1999, individual members of the Grevillea Study Group – a part of the Australian Native Plants Society (Australia) – had conducted no less than four private and unofficial searches in the Hartley area.

As most of the area is now degraded, private farm land, these searches consisted of fence-peering and traipsing through road verges (no trespassing, of course!).

In November 1999, a Grevillea crawl was conducted in the area. On Saturday morning, November 6, while a number of the party travelled to Lithgow to vote for the republic that was not to be, Anders Bofeldt , Wollongong Botanic Gardens, decided to take a walk in the area where we had encamped the night before. On returning to camp, he asked innocently what this particular pink-flowered plant was that he had just collected.

The specimen was from a single plant that appeared to be about 30 years old, judging from the main stem which was the thickness of a man’s arm. Grevillea rosmarinifolia – rediscovered!

Bibliography

Cunningham A. (1825). A specimen of the indigenous botany of the mountainous country between the colony round Port Jackson and the settlement of Bathurst; Botany of the Blue Mountains in Barron Field’s Geographical Memoirs of New South Wales (P.328), John Murray, London.

Fraser C. (1828) A Catalogue of Plants cultivated in the Botanic Gardens, Sydney, New South Wales, January 1828. Unpub. MS.

Graham R. (1826) Dr Graham’s List of Rare Plants. Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal 1: 172-173, Adam Black, Edinburgh.

Hooker J. D. (1872) Grevillea rosmarinifolia. Botanical Magazine 98 Tab. 5971

Hooker W.J. (1826) Grevillea pubescens. Exotic Flora 3:t 216, London

Loddiges C. (1829) Grevillea rosmarinifolia. The Botanical Cabinet 15: t. 1479, Arch, London.

Loudon J.C. (Ed.) (1830) Hortus Britannicus Part 1: 39, Longman Rees, London.

McGillivray D.J. (1975) Australian Proteaceae: New Taxa and Notes Telopea 1(1):30

McGillivray D.J. assisted by R.O. Makinson (1993) Grevillea Proteaceae A Taxonomic Revision, Melbourne University Press, Carlton.

Olde P.M. & Marriott N.R. (1994) The Grevillea Book Vol.1:112-114, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst.

Sweet R. (1827) Hortus Britannicus P. 348, James Ridgeway, London.

Sweet R. (1827-1828) Grevillea rosmarinifolia. Flora Australasica t.30, James Ridgeway, London.

| What is the ‘type’ form? |

|

When a plant is officially described and named, the description is based on a collected specimen of the plant. This specimen is often (but not always) the first specimen of the plant that was collected from its natural habitat. The specimen used for this official description is called the ‘type’ of the species. The process requires that a single specimen only be designated and this is called the holotype. Duplicates or parts of the original specimen are called isotypes and may be distributed to a number of herbaria throughout the world as reference material. The “type” form of a species is a plant collected from the same population as the holotype. Since Grevillea rosmarinifolia was collected by Allan Cunningham along the Coxs River, near Bathurst, New South Wales, plants from this population with similar appearance are known as the ‘type’ form. G.rosmarinifolia has a wide distribution and has many populations that differ significantly in appearance. It is important then to understand that the type form may differ in a number of characteristics from forms of the species found in other locations. These differences (eg, leaf shape and arrangement, flower structure) may sometimes be sufficient to warrant other forms or populations being described as separate taxa or species. In G.rosmarinifolia, there are in fact two subspecies. Subsp. rosmarinifolia remains as the type subspecies but subsp. glabella has been typified from a second population in western New South Wales. Like subsp. rosmarinifolia, it also has a ‘type’ specimen. Experts may disagree on the significance of the differences in the various forms of a species and, following research, it is not unusual for a new species to be “split” off from the type form. For example, Grevillea divaricata has recently been recognised as distinct from G.rosmarinifolia and been split off. |

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)