Acacia – Background

Introduction

Acacia is a genus of around 1000 species, most of which occur in Australia with another dozen or so being found in Asia. Until recently the genus was more broadly described with about 1400 species spread over five sub-genera. This is discussed further below (see “Acacia, Vachellia and Racosperma“).

Acacias occur in all Australian states from coastal zones to mountains to the dry inland. Collectively, acacias are known as “wattles” and one of them, Acacia pycnantha, is the national floral emblem. The green and gold colours of the foliage and flowers has provided Australia’s official colours.

The derivation of the term “wattle” is interesting. “Wattle” is an old English word meaning interlaced rods and twigs. In the early years of the European settlement in Australia, shelters were constructed of flexible sticks woven together and plastered with mud, a technique known as “wattle and daub” and the wood most commonly used came from a plant now called Callicoma serratifolia which became known as “Black wattle”. Callicoma has Acacia-like flowers but is not closely related to Acacia. However, because of the similarity in flowers, the term “wattle” eventually became associated with all Australian acacias and, even more confusingly, “Black wattle” is also applied to some Acacia species.

Characteristics

|

| Nodules on the roots of a leguminous plant Photo: Brian Walters |

Together with the ‘pea-flowered’ plants and another group which includes Senna and Cassia, acacias are legumes and are able to take-up (“fix”) their nutrient requirements for nitrogen directly from the atmosphere with the aid of soil bacteria (Rhizobium sp). This occurs in nodules on the roots of the plants, as shown in the photograph.

Australian acacias are generally small to large shrubs but there are a few which become large trees. The individual flowers are very small but are arranged into rod-like or globular heads of a large number of flowers. The colour is almost invariably in the range between white and bright yellow but one solitary species (A.purpureapetala) has mauve flowers and a recently discovered form of the normally yellow-flowered Acacia leprosa has deep pink flowers. This form has been given the cultivar name “Scarlet Blaze”

Many Australians regard the flowering of wattles as signaling the coming of spring and it’s true that many commonly grown species flower in late winter. However, it’s equally true that a wattle can be found in flower somewhere at any time of the year. Following flowering, seeds develop in pods (legumes) which vary in shape between species and may be flat, short, elongated or cylindrical.

In the majority of species, the compound (bipinnate) leaves which appear on all Acacia seedlings are quickly replaced by flattened stalks known as phyllodes, as shown in the diagram.

Phyllodes have a leaf-like appearance and can be enormously variable in size and shape. A few species, such as the well-known “Cootamundra wattle” (A.baileyana) and “Mudgee wattle” (A.spectabilis), retain the compound, fern-like leaves throughout their lives.

Many Acacia species occur in areas where bushfires are common, such as dry forests and woodlands. In these habitats they are often “pioneer” species, quickly recolonizing burnt-out areas and then being gradually replaced by other species in the plant community. They are often helped in this role by ants which store the seeds underground. The seeds themselves usually have a very long viability.

Botanical Classification

The botanical classification of the legumes is a little confusing. In Australia, until recently, most authorities classified them as belonging to three distinct families – Fabaceae (typical ‘pea-flowered’ plants), Mimosaceae (Acacia and relatives) and Caesalpiniaceae (Senna, Cassia and relatives). However, around the world the they have usually been classified in a larger Fabaceae family, with three subfamilies:

- Sub-family Faboideae – typical ‘pea-flowered’ plants (previously family Fabaceae)

- Sub-family Mimosoideae – Acacia and relatives (previously family Mimosaceae). The family/sub-family names based on the Mimosa genus.)

- Sub-family Caesalpinioideae – Senna, Cassia and relatives (previously family Caesalpiniaceae).

This latter classification now seems to have been adopted by Australian herbaria and is also used on these ANPSA pages. However, more recent studies indicate that a new classification comprising six sub-familes is warranted. Under this revised classification, the Mimosoideae would be included in sub-family Caesalpinioideae (see “New Subfamily Classification of the Leguminosae and Insights into Plastomes of the Mimosoid Clade“).

Acacia, Vachellia and Racosperma

A long running debate about the classification of Acacia was resolved at the 2011 Botanical Conference held in Melbourne.

The debate arose out of research over the past few decades which established that the two main groups of acacias (the African and Australian groups) were distinct and needed to be separated into different genera. The debate centered around the issue of which group of plants would retain the name Acacia, based on the following opposing views:

- Those supporting the retention of Acacia for the African group argued that the genus was originally described from an African species, A. scorpioides (syn. A. nilotica).

- Those supporting the retention of Acacia for the Australian group argued that the vast majority of species occurred in Australia and that reclassification of those species would incur considerable disruption and expense.

The issues involved are discussed further in the following articles:

- Proposed Name Changes in Acacia.

- Another view on Racosperma.

- Acacia Name Issue (from the World Wide Wattle website).

One consequence of the adoption of the first view would have been that most Australian acacias would have been reclassified into a new genus, Racosperma.

However, the decision of the 2005 Botanical Conference, and confirmed at the 2011 Conference, was that the name Acacia should be retained for the Australian species and that the (mainly) African species should be reclassified into the genus Vachellia. This involved specifying a new type species for Acacia, A. penninervis.

Overall, the species formerly classified as Acacia are now spread across five genera:

- Acacia: 1032 species, Australia, Asia

- Acaciella: 15 species, Americas

- Mariosousa: 13 species, Americas

- Senegalia: 199 species, Americas, Africa, Asia, Australia

- Vachellia: 156 species, Americas, Africa, Asia, Australia

(Source: World Wide Wattle)

The impact of the 2011 Botanical Congress decision on Australian acacias is that nine species have been reclassified as Vachellia and two have been reclassified as Senegalia. All of the remainder (over 950 species) remain in Acacia.

Commercial and Other Uses

Several Acacia species provide commercial returns both in Australia and overseas. The bark of A.mearnsii (one of the “Black Wattle” group) is valuable in the tanning industries and commercial plantations exist in a number of countries (eg.South Africa, Brazil). Unusually, Australia actually imports much of its need for A.mearnsii bark tannin from South Africa where the tree has unfortunately escaped from plantations to become a pest species. The quick-growing characteristics of many of the larger species makes them useful for soil erosion control and for providing fuel for cooking and heating.

Australian aborigines traditionally used the seeds and roots of a number of Acacia species as a food source but it is only fairly recently that research has started to be undertaken by a number of organisations to determine the nutritional potential of several species as well as any potential toxic effects. Some limited use of Acacia as a food is occurring in the “bush food” industry with, for example, ground Acacia seeds being used as a component of a bread known as “Wattle Damper” and as a flavouring for ice cream.

Acacia – Propagation

Introduction

Virtually all acacias are propagated from seed. This is a reliable method which, with most commonly grown species, presents few problems. In the last few years a number of species have been successfully propagated from cuttings and this trend can be expected to increase.

Seed

The seed of Acacia species is shed annually. When the seed is ripe the pods turn brown and split to release the seeds. By keeping watch on the ripening pods it is fairly easy to collect the seed before it is shed.

Acacia seeds have a hard coat which, in most cases, is impervious to water and germination will normally not occur unless some sort of pretreatment is first carried out. In nature this hard coating is designed to be broken down by the heat of a bushfire to allow the species to re-colonize burnt out areas.

|

| Acacia seeds swell noticeably (right) when they are ready to sow Photo: Brian Walters |

This effect can be replicated in a number of ways but, for most species, the easiest is to pour boiling water over the seeds and allow them to stand overnight. The next day any seeds which have swollen are ready for sowing and can be removed; the remainder of the seeds can be treated with boiling water again and the process repeated for as long as necessary.

In some cases, however, the seeds will not tolerate excessive time in boiling water and respond better to a one minute immersion in boiling water followed by cooling down. Species in this category are likely to be those native to areas where relatively quick grass fires occur which subject the seed to shorter duration heat than would occur in forest environments.

There are also a few Acacia species from inland and tropical areas which do not require treatment prior to sowing and may, in fact, be killed by boiling water.

Another method of pretreatment is to rub the seeds between sheets of sandpaper to reduce the thickness of the outer coating so that moisture can penetrate.

Acacia seed usually germinates well by conventional sowing methods in seed raising mixes. Pre-germination, by sowing into a closed container containing moist vermiculite or a similar material, is also a useful method. Using this method, germination usually occurs in 1-2 weeks and when the root has reached about a centimetre or so in length, the seedling can be placed into a small pot of seed raising mix.

Cuttings

Although not regularly used with acacias, propagation from cuttings is possible and a number of named cultivars are now being routinely produced by this method. Best results are achieved with cuttings of about 75-100mm in length of mature, current season’s growth with the foliage removed from the lower two-thirds of the stem. “Wounding” the lower stem by removing a sliver of bark and treating the lower stem with a “root promoting” hormone both seem to improve the success rate.

General Propagation

Further details on general plant propagation can be found in the Plant Propagation section.

Acacia – Cultivation

Spoiled for Choice

There are over 900 species of Acacia that are native to Australia and, although only a fraction of that number are readily available, selecting suitable species for any given situation rarely presents a problem. Acacias are often regarded as being quick growing but short lived and to a certain extent this is true but they are particularly useful for providing quick growth to cover the stark, empty look of a new garden. Most should live from 12 to 15 years in suitable conditions but many will last much longer.

The accompanying table lists 20 wattles, most of which are suited to temperate areas unless otherwise indicated. The majority should be reasonably easy to obtain. Of course, you can always grow your own plants if particular species prove difficult to obtain – see the “Propagation” tab above.

Some of the Best Acacias

|

Species

|

Common Name

|

Size HxW (m)

|

Flowering Period

|

Flower Colour

|

Comments

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A.adunca

|

Wallangarra Wattle

|

5 x 3

|

Wi/Sp

|

Yellow

|

Sunny, well drained location.

|

|

A.amblygona Prostrate

|

None

|

0.3 x 1.5

|

Wi/Sp

|

Gold

|

Sunny, open position. Excellent in a rockery.

|

|

A.boormanii

|

Snowy River Wattle

|

4 x 3

|

Wi/Sp

|

Yellow

|

Attractive greyish foliage. Best in cold climate.

|

|

A.buxifolia

|

Box-leaf Wattle

|

3 x 2.5

|

Wi/Sp

|

Yellow

|

Hardy in sun and semi-shade and withstands extended dry conditions.

|

|

A.cognata

|

Bower Wattle

|

6 x 5

|

Wi/Sp

|

Lemon

|

Numerous small growing cultivars now available which look wonderful in large containers (eg. ‘Bower Beauty’, ‘Limelight’, ‘River Cascade’ ‘Waterfall’).

|

|

A.conferta

|

None

|

2 x 2

|

Au/Wi

|

Gold

|

Small grey-green phyllodes. Flowers in globular heads on long stalks.

|

|

A.cultriformis

|

Knife-leaf Wattle

|

4 x 3

|

Sp

|

Yellow

|

Small blue/grey phyllodes with a triangular shape. Graceful growth habit.

|

|

A.elongata

|

Swamp Wattle

|

2 x 2

|

Wi/Sp

|

Yellow

|

Erect growth habit. Tolerates poor drainage.

|

|

A.fimbriata

|

Fringed Wattle

|

5 x 3

|

Wi/Sp

|

Gold

|

Dense, attractive foliage with lightly scented flowers. Small forms available.

|

|

A.flexifolia

|

Bent-leaf Wattle

|

1.5 x 1.5

|

Wi

|

Lemon

|

Small, attractive shrub for many areas. Withstands extended dry periods.

|

|

A.glaucescens

|

Coast Myall

|

10 x 8

|

Wi/Sp

|

Yellow

|

Very attractive tree with ornamental blue/grey foliage.

|

|

A.leprosa ‘Scarlet Blaze’

|

Cinnamon Wattle

|

5 x 3

|

Wi/Sp

|

Orange/red

|

Red flowers are unusual in Acacia. Best for areas of low humidity.

|

|

A.merinthophora

|

None

|

3 x 2.5

|

Wi

|

Yellow

|

Unusual long, narrow phyllodes. Best for areas of low humidity.

|

|

A.myrtifolia

|

Myrtle Wattle

|

1.5 x 1.5

|

Wi/Sp

|

Cream

|

Attractive small species with reddish stems that contrast well with the pale flower clusters.

|

|

A.oxycedrus

|

Spike Wattle

|

5 x 3

|

Wi/Sp

|

Lemon

|

Very, very ornamental but very, very prickly!

|

|

A.pravissima

|

Ovens Wattle

|

4 x 3

|

Wi/Sp

|

Gold

|

Very ornamental. At least one prostrate form is available (‘Golden Carpet’) that makes an unusual groundcover.

|

|

A.pulchella

|

Western Prickly Moses

|

1.5 x 1.5

|

Wi/Sp

|

Gold

|

Mainly for areas of low humidity. Very ornamental with ferny foliage.

|

|

A.spactabilis

|

Mudgee Wattle

|

4 x 2.5

|

Wi/Sp

|

Yellow

|

One of the most ‘spectacular’! Beautiful ferny foliage.

|

|

A.terminalis

|

Sunshine Wattle

|

2 x 1.5

|

Au/Wi/Sp

|

Lemon to Gold

|

Attractive plant with ferny foliage. Variable flower colour.

|

|

A.vestita

|

Hairy Wattle

|

4 x 3

|

Sp

|

Gold

|

Attractive, weeping growth habit. Requires watering during extended dry periods.

|

A few species of Australian acacias have proved to be weed pests both in Australia and in other parts of the world. In South Africa, for example, A.saligna, A.cyclops, A.melanoxylon, A.mearnsii, and A.decurrens cause serious problems and no natural predators exist to keep them under control. Within Australia, A.paradoxa has been reported as being a problem in parts of Victoria and even the popular Cootamundra wattle (A.baileyana), Queensland silver wattle (A.podalyriifolia) and golden wreath wattle (A.saligna) are weeds of the Sydney bush and other areas. These species should not be planted in gardens in the vicinity of natural bushland. These and other problem species are listed in our Environmental Weeds section.

Maintenance of wattles in the garden is fairly straight forward and should not involve much more than a light pruning to shape the plant in its early years and an occasional application of fertilizer, preferably of a slow-release type. Most wattles will not recover from a severe pruning so always ensure there is green foliage below any cut.

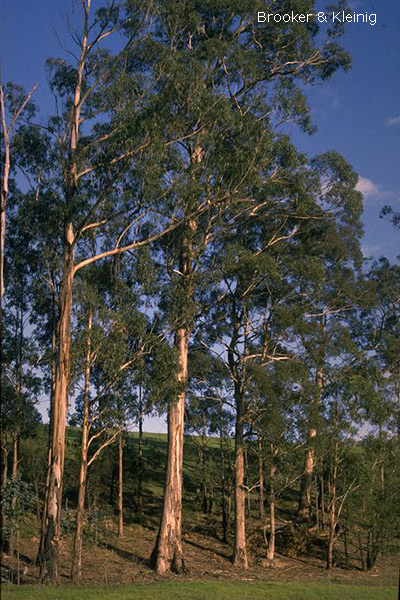

Photo: Brian Walters

Borers

Everyone knows that wattles are susceptible to borers, don’t they? It’s just a fact of life.

But are they?

Borers mainly affect some of the tree species, particularly those in the ‘Black Wattle’ group which includes A.decurrens, A parramattensis and A.mearnsii. These trees often grow very rapidly but then deteriorate after 7-8 years as the damage inflicted by borers becomes more than the plant can cope with. By the time the tree dies, it is often very large and spreading and difficult to remove safely. This group is probably not ideal for small suburban gardens. Not all large wattles are subject to borer attack. Acacia elata (Cedar Wattle), for example, is a magnificent tree which is very long lived although perhaps too large for all but very large gardens.

Many of the smaller wattles are probably no more susceptible to borers than other garden plants and control, if needed can be readily achieved by skewering the pest with a wire inserted into the hole in the trunk or branch.

Acacias and Allergies

Wattles have been widely accused of causing hay fever. But does this stack up to scrutiny?

There is no doubt that some people are allergic to Acacia pollen but there is also no doubt that many allergies attributed to wattles are, most likely, caused by pollen from grasses and other plants that happen to be flowering at the same time.

The general consensus among researchers seems to be that the pollen of wattles is relatively heavy and is not carried long distances by breezes. The Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA) has this to say:

“Wattle is frequently blamed for early spring symptoms but allergy tests (skin prick tests) seldom confirm that wattle is the true culprit.“

Furthermore, as reported in the Acacia Study Group newsletter, there has been a recent, detailed study on the subject allergic rhinitis (‘hay fever’) in Australia by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (an Australian Government Agency).

The 48 page report covers matters such as the causes of allergic rhinitis, its prevalence within the Australian community and management of the problem. Various causes are discussed, including sensitivity to pollen. In this regard, the report notes that “the tiny, hardly visible pollens of wind-pollinated plants are the predominant triggers.” The report also states that “pollens of insect-pollinated plants (such as Australian wattles) are too heavy to remain airborne and pose little risk“.

Some particular pollens to which sufferers are commonly allergic are listed, and these include grasses, some flowering plants such as pellitory weed, Patterson’s curse, ragweed and parthenium weed, and some trees such as silver birch, olive tree, English oak, and Murray pine.

Reference: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2011. Allergic rhinitis (‘hay fever’) in Australia. Cat. No. ACM23. Canberra: AIHW

The report can be downloaded in full from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s web site.

Distinctive Features of Acacia

Marion Simmons

|

| Figure 1 – Phyllodes and Leaves 1 and 2: Phyllodes of different shapes 3: Fern-like (bipinnate foliage) 4: Winged stems, the only foliage on some species 5: A phyllode showing net-veins 6: Phyllodes are reduced to spines on some species |

Marion is a former leader of the Society’s Acacia Study Group and author of several books on the genus. The following is part of a longer article which appeared in the March 1988 issue of the Society’s journal “Australian Plants“.

* * * * * *

Phyllodes and Leaves

The majority of Australian Acacias produces “leaves” or phyllodes of great variety. These phyllodes are not really leaves but are flattened leaf stalks which have adapted to look like and function as leaves. Size is extremely variable and some of the phyllodes are huge – up to 30 cm long. Some are so small they appear to be absent as they are often reduced to small scales or spines. Occasionally the stems have distinctive wide wings (as in A.glaucoptera and A.alata) with tiny phyllodes present.

A number of the acacias have bipinnate (fern-like) leaves, made up of a large number of small leaflets (pinnules) along a central stalk. The tree species with this leaf type are usually found in the eastern states and another group about 1 m tall with similar leaves occurs in Western Australia, with the exception of A.mitchellii, which occurs in South Australia, Victoria and New South Wales.

|

| Figure 2 – Flowers 1. A ball flower head enlarged to show individual flowers 2. One single flower enlarged 15 times 3. Ball flower heads in racemes (spikes of flower) 4. Ball flower heads, solitary, from a phyllode axil 5. Rod flower head and a phyllode with 3 veins or nerves |

Phyllode details are important as they are used as “key” characters in identification. Some important things to note are size and shape of the phyllodes, the type and number of veins, whether penni- or net-veins, length of leaf stalk and gland position.

The gland is an indented or raised part usually occurring at the base of or on the top margin of the phyllode or on the leaf stalk of the fern-like leaves. These are extra-floral nectaries which produce very small, varying quantities of nectar to which insects and occasionally birds are attracted.

Flowers

Some acacias flower in their first year, others take longer. Flower buds may be produced at any time of the year, depending on the species; plants usually flower in great profusion once a year. Flowering time may vary in length from a few weeks to many months, once again depending on the species and often the season. the availability of soil moisture, particularly in the arid zones, determines whether some of these species flower at all in any one year.

Acacia flowers vary considerably in size and occur in the form of balls or spikes. The flowers are usually bi-sexual (having male and female parts on the same flower) with 4-5 or occasionally more sepals and petals. The flower heads are made up of a few or many tiny individual flowers with numerous free stamens, as illustrated in the diagram.

Flowers are attached to the stem in different ways. Many ball and spike flowers occur on simple stalks and many on racemes (branched stalks) which sometimes extend into panicles (branched racemes).

Flowers vary in colour from almost white through shades of cream and yellow to orange. At least one species, A.purpureapetala, differs from the usual colour range, and produces mauve or purple flower heads.

Acacia Study Group

The Acacia Study Group is one of a number of Study Groups within ANPSA. Its aim is to further knowledge about the cultivation, propagation and conservation of members of the genus Acacia. The Study Group has been in operation since 1961 and during that period more than 150 detailed and informative newsletters have been published.

Further information about the Study Group, its activities and access to the newsletter archive can be found at the link below.

Let’s celebrate Wattle Day!

Jeff Howes

On September 1, 1988 The then Governor General of Australia, Sir Ninian Stephen, officially proclaimed Acacia pycnantha the Golden Wattle as Australia’s national floral emblem. The proclamation ceremony was held in the National Botanic Gardens Canberra. It included planting of seven small specimens of Acacia pycnantha at the entrance to the Gardens.

History of Wattle Day

On September 20, 1889 William Sowden, later to be knighted, an Adelaide journalist and Vice President of the Australian Natives Association in South Australia suggested the formation of a Wattle Blossom League. Its aims, set down in 1890, were to “promote a national patriotic sentiment among the woman of Australia”. One way of doing this was to wear sprigs of wattle on all official occasions. After an enthusiastic start the group folded. However, their presence inspired the formation of a Wattle Club in Melbourne. During the 1890s parties were led into the country on September 1 each year to view the wattles.

The concept of Wattle Day grew stronger and spread to New South Wales where the Director of the Botanic Gardens, J H Maiden called a public meeting on August 20, 1909 with the aim of forming a Wattle Day League. As a result of this meeting the first Wattle Day was held on September 1, 1910 in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide. On that day the Adelaide committee sent sprigs of Acacia pycnantha to the Governor and other notables in Adelaide. It was this wattle that become accepted as the official floral emblem.

Celebration of Wattle Day reached its height during World War 1. The day was used to raise funds for the war effort and many trees were denuded in order to supply the many sprigs of wattle sold on that day. Boxes of wattle were sent to soldiers in hospitals overseas and it become a custom to enclose a sprig of wattle with each letter to remind our soldiers of home. After the war Wattle Day was kept alive in schools. In 1917 however the date of Wattle Day was changed to August 1, for convenience, as that year had an early spring! In 1937 another date change, this time back to September 1 as this was the start of the school holidays!

Now as everyone knows Wattle day is officially September 1. My Spicers desk calendar has the following quote for September 1 this year “The soft golden wattle blooms brightly in Spring; So why do we still call the daffodil, king?” – a good question.

Sentiment has always been associated with the yellow flowers of the wattle, but the common name developed from a more practical use of the plant. The early convicts and colonists of around Sydney wove what they called ‘black wattle’ to build the walls of their huts. They then daubed mud on the surface, inside and out, to make a more permanent structure. This “wattle and daub’ building method is the oldest known method for making a weatherproof structure and was used as far back as the Iron Age (1100 BC). Different plants are used for “wattle” – interestingly acacias were NOT used in early Sydney times. Rather, Callicoma serratifolia — commonly called black wattle – was mainly used and and that name is preserved in Black Wattle Bay (Sydney), an early source of that plant. The 20 volume Oxford Dictionary of 1989 states that “wattle” is an old English word of dubious origin.

|

| Acacia spectabilis: Mudgee wattle Photo: Brian Walters |

Of course “wattle” refers also to the flap of coloured skin that hangs from each side of the face of some birds….eg. the domestic fowl. To confuse the issue even further there are two wattle birds in Sydney and the Lttle Wattle Bird’ is wattleless! The other, the Red Wattle Bird, has, of course, red wattles.

Acacia species

Acacias grow in many parts of the world. They occur in all states of Australia and in all continents other than Europe and Antarctica. When George Bentham compiled his ‘Flora Australiensis‘ in the 1860s there were 293 species of Acacia officially recognised in Australia. Today there are approximately 900 species. Unfortunately some are officially categorised as weeds (especially in other countries). Its perfume and dense clusters of bright yellow/gold flowers captivate all those who see the wattle and it is interesting to note that each ‘pom pom’ flower is actually many flowers each of them perfectly formed. Not all species have golden flowers – they range from bright yellow to pale yellow or creamish white.

Nearly all species germinate readily, even when seed is several years old, provided the outer covering of the seed (the testa) is sufficiently abraded to ensure penetration of water when the seed is soaked in preparation for sowing.

Although other species are more abundant and easy to grow (Acacia baileyana is one good example) Acacia pycnantha now reigns officially as our national emblem. A.pycnantha is a shrub of small tree about 4 to 8 metres tall and occurs in the under-storey of open forests or woodland and in open scrub formations in SA, VIC, NSW and the ACT, in temperate regions with mean annual rainfall of 350 to 1000 mm. It needs good drainage but tends to be short lived in cultivation. However, in spring you are rewarded with large fluffy golden yellow flowerheads with up to 80 minute sweetly scented flowers that provide a stark contrast to the bright green foliage.

Based on an article in the August 1997 issue of “Blandfordia”, the newsletter of SGAP’s North Shore Group.

For further information on Wattle day, its history and activities, see the web site of the Wattle Day Association.

Acacia – Further Information

A number of books have been written specifically on acacias and most general books on Australian native plants will contain useful information on their botany and horticulture. There are also a number of Acacia resources on the internet and on CD. Some of the most detailed references are listed below.

Books:

- Armitage, I (1977), Acacias of New South Wales, Society for Growing Australian Plants, NSW Region.

- Elliot, W. R and Jones D (1982), The Encyclopaedia of Australian Plants, Vol.2, Lothian Publishing Company Pty Ltd, Melbourne.

- Hitchcock, M (1991), Wattle, Australian Government Publishing Service.

- Pedley, L (1987), Acacias in Queensland.

- Rogers, F, Field Guide to the Wattles of Victoria.

- Simmons, M (1981), Acacias of Australia, Vol.1, Thomas Nelson Australia.

- Simmons, M (1987), Growing Acacias, Kangaroo Press.

- Simmons, M (1988), Acacias of Australia, Vol.2, Penguin Books Australia.

- Tame, T (1992), Acacias of South-east Australia, Kangaroo Press.

- Wibley, D (1980), Acacias of South Australia, South Australian Government Printer.

Journals:

Several issues of the Society’s journal “Australian Plants” are particularly useful for those interested in Acacia.

- Vol 10, No.82 March 1980; Microwave treatment of Acacia seed.

- Vol 11, No.91 June 1982; Wattles of the Grampians.

- Vol 14, No.114 March 1988; Outline of characteristics of Acacia.

- Vol 17, No.134 March 1993; Top End wattles for gardens.

- Vol 18, No.147 June 1986; Vegetative propagation of wattles.

- Vol 21, No.169 December 2001; Acacia leprosa ‘Scarlet Blaze’ – Victoria’s Federation flower.

- Vol 22, No.180 September 2004; Entire issue.

Internet:

- On-Line Key to Acacia – WATTLE ver 3 This is an interactive, web-based service to help people identify any species of wattle and access further information on a particular species.

- Acacia – Australian National Botanic Gardens. Includes many species and photos.

- Acacia Study Group newsletters – recent issues are available here.

- Acacia – An Introduction

- Acacia Seed Raising

- A Simple Botany of Wattles

- Acacia leprosa “Scarlet Blaze” – a red-flowered wattle!

- Acacia leprosa and “Scarlet Blaze”

- Acacia Name Issue

- Another view on Racosperma.

- Cheery Acacias

- Dead Finish – Acacia tetragonaphylla

- Edible Acacias

- Golden Wattle – Acacia pycnantha, Australia’s floral emblem.

- Growing Native Plants – a series of plant profiles by the Australian National Botanic Gardens; includes a number of acacias.

- If You Start Sneezing don’t Blame the Acacias

- Mulga – Acacia aneura

- Proposed Name Changes in Acacia

- Wattles and Bushfires

- Wattle Day Association

- Wattle It Be? By Seed or Cuttings? – Tradition says that wattles can’t be easily grown from cuttings. Stupid tradition….

- WattleWeb Produced by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney – documents the acacias of New South Wales, with descriptions of the species, notes on distribution, ecology, images (planned) and identification keys.

- World Wide Wattle An extensive site designed to inform, educate and promote the conservation, utilisation and enjoyment of Australian Acacia species.

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)